© ancestry.co.uk

Thank you to Patricia Brazier for the following research.

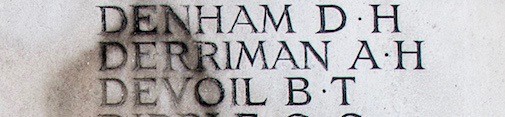

Arthur was baptised at St Paul’s church in Herne Hill on 9th February 1890. His father is James Thomas Derriman, a paper layer and his mother is Eliza Bull. Their address is 13 Jessop Road, Herne Hill.

In the 1891 census, the family are still living at 13 Jessop Road. Arthur has five brothers: William age 19, Alfred age 15, Vincent age 13, Charles age 10. He also has a sister Elizabeth who is 4 years old.

The family are still living at Jessop Road in the 1901 census. Thomas (his father) is a house decorator. The older children have left home but Arthur and his sister Elizabeth are still there.

In the 1911 census Arthur is now an apprentice compositor. Living with him are his mother Eliza, she is now a widow, and his brother Vincent, who has two sons, Vincent Bertram age 12 and Cecil Alfred age 10.

His service papers show that he enlisted on 17th August 1914 at Lambeth and was attested at Winchester later that month. He is 5 feet 4 and one half inches tall, has grey eyes and dark brown hair. He arrived in France in June 1915. He then became ill with rheumatic fever and returned to England. After recovering he returned to France in June 1916.

Arthur married Lilian Margaret Cooper at the parish church in Dorking on 19th December 1916. Arthur’s address at the time is Jessop Road in Herne Hill. Lilian’s address is 20 St Martins Place Dorking. Lilian was a housemaid at Kempshott Park near Winchester; they must have met when Arthur was in the Barracks at Winchester. She was born in Dorking and her family lived there. Their daughter Margaret was born in Dorking in the March quarter of 1917. Lilian was the sister of Arthur James Cooper.

Arthur returned to his battalion near Aubigny and in April 1917 was admitted to hospital with Synovitis of the ankle. He stayed for 2 days and then returned to his unit. His battalion saw action in many battles in 1917 including Vimy Ridge, The 1st and 2nd battles of the Scarp and Cambrai. On the 19th November 1917 Arthur was appointed to Lance Corporal.

In March 1918 his battalion were fighting on the front line at Bois D’urvilliers. On 23rd March Arthur was wounded in the left leg. He was taken prisoner along with many others including Colonel C. Howard Bury and taken to Cassell in Germany.

Here is an extract from the war diaries from that time:-

The following graphic account of what actually befell the 9th Bn. on the night of March 20th and morning of March 21st, by Colonel C. Howard Bury, D.S.O., who was in Command at the time, shows clearly the gallant stand that was made and how they were overwhelmed.

21st Mar. The Great German OFFENSIVE of 1918

BOIS D’URVILLERS SECTOR

The night of March 20th-21st found the 9th Bn. holding the Urvillers Wood sector of the front line, with the 8th Bn. K.R.R. on their left and the Somerset Light Infantry on their right. In support, at Montescourt, were the 5th Oxford and Bucks L.I., with the 9th R.B. in reserve at Jussy. The front, consisting of about 2000 yards, was held by posts, three or four hundred yards apart, with no lateral communication. From the support line communication trenches ran out to each post. C and B Companies were holding the front line, each with two platoons in the front line and two in -support. A Company was holding the three so-called strong points, with one platoon, on the St. Quentin Road. D Company was in reserve, over two miles behind, at Brigade Headquarters, so that the Battalion was very much scattered in small groups over a wide extent of country. The whole system of defence depended, therefore, on accurate rifle and machine-gun fire, coupled with accurate information which would enable the down a barrage artillery to co-operate and put wherever required.

The night was an exceptionally fine one, and at midnight the moon was shining brightly. The Germans had for some time past been keeping very quiet on this front, and during the night the only unusual sign was the constant rumble of their transport, which lasted all through the night. This was reported to our artillery, who opened a harassing fire along the roads and approaches in the German lines.

Everyone had been warned that the Germans would probably make an attack in the early morning, but as the same warning had already been given out on several previous occasions, no especial anxiety was felt. This time, however, the information proved to be correct, and at 4.30 a.m. a heavy bombardment opened all along the line, and extended to the north and south as far as the eye could reach. The darkness at the time was intense, as a thick fog had rolled up since midnight, and it was impossible to see a yard in any direction. A great number of guns must have been used during the bombardment, as shells appeared to be falling everywhere, with a great many passing overhead on their way to the batteries behind. The majority of the shells at first appeared to be gas shells, and the air rapidly became impossible to breathe without respirators. By the time the bombardment had lasted two hours every telephone line from Battalion Headquarters had been broken. At the start Battalion Headquarters were in touch with the battalions on their right and left, with all the Companies and with Brigade Headquarters; but in this weakly-held sector, where communications and early accurate information were of the most vital importance, no attempt whatever had been made to bury any of the telephone lines.

When the Battalion were supposed to be out resting, instead of being able to train the men they were all taken for working parties, digging new strong points or new trenches, which were overrun by the Germans in the first few hours, owing to there being no men to hold them for want of accurate information. The bombardment equally broke the telephone lines between Brigade and Divisional Headquarters, owing to their being laid on the surface of the ground instead of being buried.

At 9.30 a.m. the hostile barrage gradually moved backwards until it rested behind us. The fog was still as dense as ever, and it was impossible to see five yards in any direction, so that our visual signalling, S.O.S. rockets or pigeons, were quite useless.

At 10 a.m. a runner came from C Company to say that the enemy had come over in the fog and were already on the Pechine Line (our main line of resistance in the outpost line). Immediately afterwards a runner from A Company came in to say that the Company Commander, Captain Singlehurst, had been killed, and that the Germans had reached the St. Quentin Road.

This information was sent off by power buzzer and by runner immediately to Brigade Headquarters, but it is doubtful whether either message reached its destination.

Shortly afterwards Rfn. Blackwell dashed out into the fog and returned with a German officer, who, when asked what he was doing there, said that he was looking for his men, who had gone on ahead. On looking at his maps, I found that his objectives were places five and six miles behind us. The maps were at once sent off to Brigade Headquarters, but never reached their destination, as the Germans were already far behind us. The officer also told me that their Divisional front for the attack was two kilometres, and that they were attacking on this front with three divisions in depth, news which was not very cheerful for us. Several small parties of Germans stumbled on to our trench in the fog, but were quickly driven away again.

About midday the fog began to lift, and it was possible to gain some idea of what had happened. Most. of our scattered posts had by this time been surrounded and mopped up one by one. Germans were to be seen everywhere: parties of them were to be seen hurrying along the St. Quentin Road, and to the south they were seen bringing up their artillery on to the ridge behind us. Our Lewis guns for a while had the time of their lives, and caused much confusion and delay to their artillery.

At 1 p.m. we fired off rockets to shew that we were still holding out, and had also sent a pigeon message saying that we were hard pressed, as the Boches had got into both ends of our trench and were trying to bomb us out. In this they were not successful, as Lieut. Mackie at one end and Lieutenant White at the other end, with a few men, managed to keep them at bay.

The only effect of the rockets was to attract the attention of more Boches, who thereupon brought up an sorts of engines of war against us, flammenwerfer, trench mortars and machine guns. The flammenwerfer were soon put out of action by rifle grenades, which were also very useful in searching out the dead ground, of which there was only too much around us, where the Germans were collecting preparatory to charging. The hostile machine guns proved much more troublesome, as they completely enfiladed our trench.

By this time more than half the small garrison were casualties, and the Lewis guns, which had done excellent work, refused to fire more than single shots. All this time the Germans had been collecting in large numbers, and just before 4 p.m. quite five hundred of them rushed in on us suddenly from all sides, and it was all over.

As a minor tactical operation, it was very well done, and they told me afterwards that they had had some months training in this type of warfare.

Their signalling and staff work appeared to be very good: their staff officers were well up in the front, and when taken to their Brigade Headquarters we found it already established behind us on the way to our old Brigade Headquarters.

The second division that was attacking on our Battalion front were the ones that finally mopped us up, and our captors proved to be Bavarians. They could not believe that only one Battalion was holding this front, and kept enquiring why we had already withdrawn our troops and guns.

Of the Battalions in our Brigade that were in support and reserve we never saw a sign.

(Colonel Howard Bury’s narrative ends at this point.)

By the evening of March 21st the Battalion had apparently ceased to exist; a few stragglers were colIected, however, at Petit Detroit on the morning of the 22nd, under Sergt. Beresford, of B Company, and attached to the 9th Battalion, Rifle Brigade.

22nd Mar.

On the night of the 22nd, Major Lacey reported at the 42nd Brigade Headquarters; he had with him some 400 details, amongst whom were included a few men of the 9th Battalion. His instructions were to cover the arrival of reinforcements who were coming to occupy the line Ugny-le-Gay–Cugny, or in the event of a break through from the north to hold the Cugny–Flavy line.

23rd Mar.

By the morning (7.30 a.m.) of the 23rd the position was again very serious, the enemy having forced a crossing of the Crozat Canal between St. Simon and Jussy. Major Lacey took up a line along the Cugny–Flavy Road, with his right on Flavy Station, and made a very determined and valuable resistance until obliged to fall back to conform on to a line round Riez de Cugny in the late afternoon of the 23rd. During the evening he was wounded and evacuated. He mentioned the Regimental- Sergeant-Major and his two runners, Rifleman Evans and Rifleman Bolton, as having done particularly well.

Arthur spent 9 months in the prison camp and was then transferred to Switzerland. In La Soldanell Chateau d’Oex he underwent several operations on his leg. There he was diagnosed with Glycaemia and eventually repatriated to England and admitted to the 4th London General Hospital. He was discharged from the army as permanently unfit for military service on 7th May 1919 and was issued with a Silver Badge No B219617. He died on 27th February 1920 and is buried at Ladywell Cemetery in Lewisham.

Lilian did not remarry and continued to live at 20 St Martins Place in Dorking for many years before moving to Woking to live with her daughter. She died in 1965 aged 71.

Their daughter Margaret married Lewis G Roberts in 1947. They had one Daughter, Margaret C Roberts born in 1954.

| Born | Herne Hill, London | |

| Lived | Herne Hill, London | |

| Son of | James Thomas Derriman and Eliza Bull | |

| Husband of | Lilian May Derriman of 20, St. Martin’s Place, Dorking | |

| Father of | Margaret Derriman | |

| Enlisted | Lambeth | |

| Regiment | King’s Royal Rifle Corps | |

| Number | A/564 | |

| Date of Death | 27th February 1920 | |

| Place of Death | United Kingdom | |

| Age | 30 | |

| Cemetery | Ladywell Cemetery |