This article was published in Westcott Local History Group newsletter in 2016. We are grateful to them for allowing us to reproduce it.

This year marks the Centenary of the Battle of the Somme. The battle started on 1st July 1916 and thousands of young men, including many from Westcott, were going into action for the first time. They had joined up in response to Lord Kitchener’s appeal for volunteers and this was the moment they had trained for, the so-called ‘Big Push’ that would break through the German lines and bring an end to the war. The day dawned bright and sunny but it was to be the worst day in the history of the British Army. We do not know how many Westcott men took part in the battle; quite a number would have been there and we do know of three with Westcott connections who were in action on that fateful first day. Two of them are remembered on our village war memorial.

Ernest Broadgate was born in Kirton in Lindsey, Lincolnshire in 1892, the son of Joseph and Lydia Broadgate who moved to Westcott shortly before the war and lived in Institute Road. We do not know if Ernest moved with them, but he enlisted in the 10th Battalion, The Lincolnshire Regiment in February 1915. Many of the northern battalions were made up of men from the same city or town, and became known as ‘Pals’ battalions. Liverpool, Accrington and Bradford all had their ‘Pals’ battalions. The 10th Lincolns clearly wanted to be different – they were known as ‘The Grimsby Chums.’

Boyd Burnet Geake was born in 1888, the son of John and Emily Geake who lived at ‘Woodlands’ in Coast Hill Lane. Boyd was a Motor Car Agent when he joined the York & Lancaster Regiment shortly after war was declared. He was later commissioned and in April 1915 married Dorothy Cutforth of Redhill before leaving for France as a Lieutenant with the 9th Battalion in August.

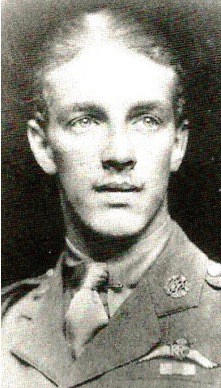

Cecil Lewis came to live in Westcott many years later, but in 1915 he was only 16 and still a pupil at Oundle School when he and a friend decided to apply for the Royal Flying Corps. They wrote off and were accepted as civilian trainees. Cecil had a gift for flying; by Christmas he was commissioned as a pilot in 3 Squadron, and by March 1916 he was serving in France. He was later to write Sagittarius Rising, one of the finest war memoirs ever written.

The battle was preceded by an immense artillery barrage which began on 24 June and continued unceasingly for five days. Some 1,500,000 shells were fired from 1,500 guns along a 20-mile front. Beneath the ground men had tunnelled towards the German lines and placed a series of huge mines under the key positions; these were timed to explode at 7.28 am, two minutes before the British infantry were to begin their attack.

Two of these mines were placed near the village of La Boiselle and the explosions were seen by Cecil Lewis (left) flying on patrol over the enemy lines. On the 50th anniversary of the battle Cecil was living in Westcott and he recorded his memories in a letter to The Times. Here is an extract:

‘At Zero minus thirty minutes, the hurricane bombardment opened up and the entire sector, right round the salient to Montauban, was covered with the flashing dirty snow carpet of bursting shrapnel. Away, detached in the beautiful morning, the reality of this fantastic spectacle hardly pierced our composure any more than the roar of 10,000 guns penetrated the roar of our own engine. Dead on time, at Zero hour, the Boiselle mines went up. A lifting column of earth rose a mile high in the sky, hung there like a silhouette of some gigantic cypress tree and fell away in a cloud of yellow dust. A second later the other mine exploded and the process was repeated. There below lay the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage lifted to the second line trenches: the tragic attack had begun.’

In the British trenches opposite La Boiselle the Grimsby Chums were waiting. They were in the first wave of the advance and La Boiselle was their objective for that day. The commanders believed that the mines and artillery barrage had effectively destroyed the German defences, and expected resistance to be light. So confident were they of success that they ordered the troops to advance at walking pace across the open ground.

However events conspired against the Lincolns. The mines had been set short of the target; they exploded in front of the German lines, not under them as planned. To make matters worse the Chums’ advance was fatally delayed to allow time for the debris to fall before the troops started forward. This gave the Germans time to regain their positions, ready for the attack. The Lincolns walked into a hail of enemy fire and men fell in swathes. Some reached the mine crater and beyond to the German trenches, but were too few in numbers to take them. Losses mounted as further attacks failed and the survivors, many wounded, lay in ‘no man’s land’ waiting for nightfall and the chance to crawl back to their lines. Only two officers and 100 men returned to answer the next roll-call; Ernest Broadgate was not among them.

The 9th York & Lancasters were part of the 70th Brigade positioned north of La Boiselle, facing the village of Ovillers. The Brigade was required to advance up Nab Valley and then push past the village to Mouquet Farm. Ovillers itself was to be attacked by the 25th Brigade. As a Platoon Commander, Boyd Geake had to take his men ‘over the top’ and lead their advance. As they started it was soon clear that the barrage had not destroyed the German positions. Their defences were very well fortified; their troops were protected in deep dugouts and as the barrage lifted they quickly returned to their firing positions. The York and Lancasters were met by intense fire and Boyd Geake was killed as they went forward. Despite heavy casualties the Brigade managed to breach the German front line, but were stopped 80 yards short of the second line by a single machine gun positioned at the head of the valley.

The first press reports of the battle were optimistic, but when the casualty lists started coming in people realised that something had gone terribly wrong. On that dreadful first day, the British Fourth Army suffered over 57,000 casualties, with more than 19,000 killed, an appalling level of loss with very little gained. Small towns with Pals battalions, like Accrington and Grimsby, suffered particularly badly. In the south the attacks of the more experienced French Sixth Army had gone well. The battle went on to November, but its outcome remains controversial. Little ground was gained, but it eased pressure on the French at Verdun. It also helped to weaken the German Army which, in March 1917, had to drop back 50 miles to shorten its line and save manpower. The human cost was enormous. It was a tragedy for all sides on an immense scale.

Cecil Lewis survived the war. He came to Westcott in 1960 and lived for nine years at ‘Springs’ in Rookery Drive. He was a man of great imagination, vigour and versatility, a man of many parts. He died in 1997 in his 99th year. An account of his life appeared in our Annual Report for 2011.

Ernest Broadgate was 23. His body was never found and he is remembered on the Thiepval Memorial which records the names of 72,000 men who died in the battle and who have no known grave. He is also remembered on his parents’ grave in our churchyard and on the war memorial at Kirton in Lindsey where he grew up. A seat in memory of the Grimsby Chums is on the rim of the mine crater known as Lochnagar, which remains as a memorial to those who fell trying to capture La Boiselle.

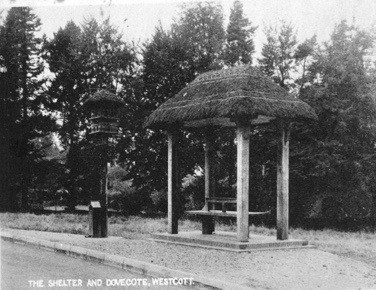

Nab Valley, where Boyd Geake fell, was later named Blighty Valley; Boyd was buried in the Blighty Valley Military Cemetery. His parents placed a stone relief of the ‘Happy Warrior’ in his memory on the north wall of the chancel in Holy Trinity. Boyd’s father, John, did a great deal for Westcott in the 1920s and ‘30s. In 1922 he arranged for the village ‘dovecot’ sign to be erected on the Green as a more prominent memorial to his son, and for the thatched bus shelter to be erected beside it. This view was probably taken in the 1920s. It was in this way that we gained our village icon and a structure that has been of lasting benefit to us ever since.

Boyd Geake’s widow, Dorothy, spent the rest of her life in Normans Cottage, Newdigate, where she and Boyd had briefly set up home together, until shortly before her death in January 1986, at the age of 100.

In 2011 we learned that Boyd Geake also had a relationship with Ethel May Clements of Seattle, as a result of which a child, Adelaide Jean Clements, was born. Adelaide later came to England and lived with Boyd’s parents. She married in 1939 and had two children who came to the village in 2011 to unveil for us a plaque on the bus shelter to replace the original which had been lost, and which bears the following inscription:

This dovecot and bus shelter were given to the village by John Burnet Geake in memory of his son, Lt. Boyd Burnet Geake, who was killed on the 1st July 1916 at the Battle of the Somme.

May they continue to inspire and serve the residents of Westcott for many years to come. Peter Bennett