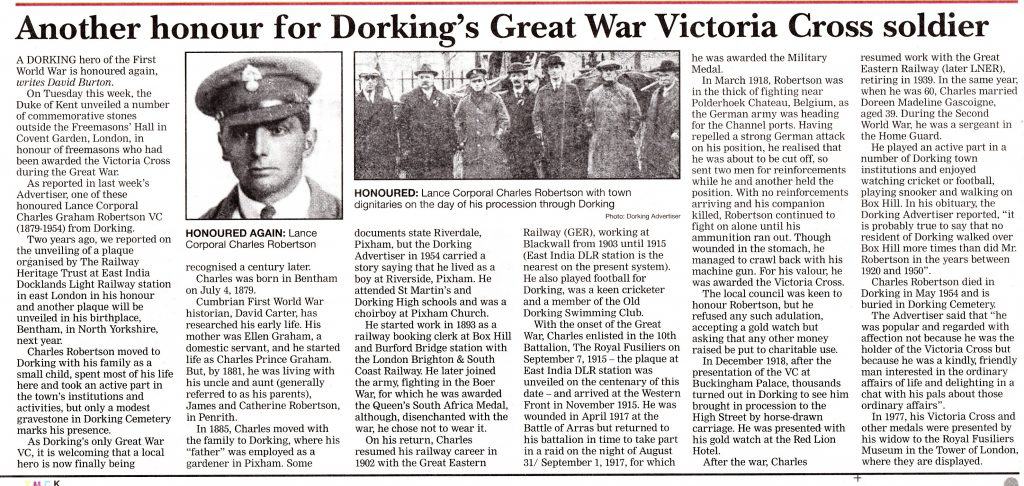

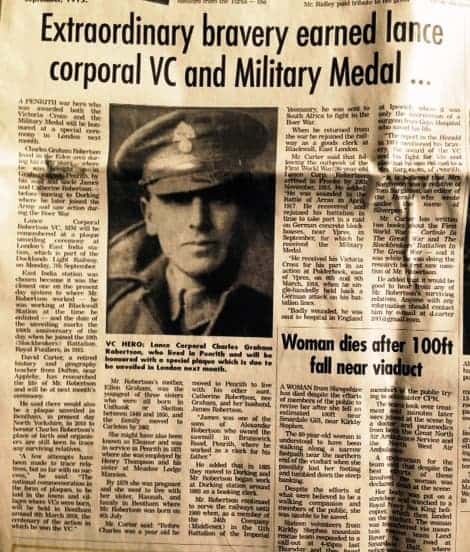

Charles Graham Robertson was born on 4 July 1879 in Bentham, North Yorkshire. Research by local Cumbrian WW1 historian, David Carter, shows his mother as Ellen Graham, a domestic servant, and his birth registered as Charles Prince Graham. By 1881, aged one, he was living with his uncle and aunt (generally referenced as his parents), James and Catherine Robertson in Penrith, while his mother married William Frederick Draycott in Rochdale in that year.

In 1885, Charles – by now Charles Graham Robertson – moved with the family to Dorking, where his ‘father’ was employed as a gardener at Riverdale in Pixham. Charles attended St Martin’s and Dorking High schools before starting work with the London Brighton & South Coast Railway in 1893 as a railway booking clerk. He later joined the army, fighting in the Boer War, for which he was awarded the Queen’s South African Medal. He came to regard that war as dishonourable and preferred not to talk about his part in it.

On his return in 1902, he resumed his railway career with the Great Eastern Railway, working at Blackwall from 1903 until 1915. He also played football for Dorking and was a member of the Old Dorking Swimming Club that raced in the river at Castle Mill.

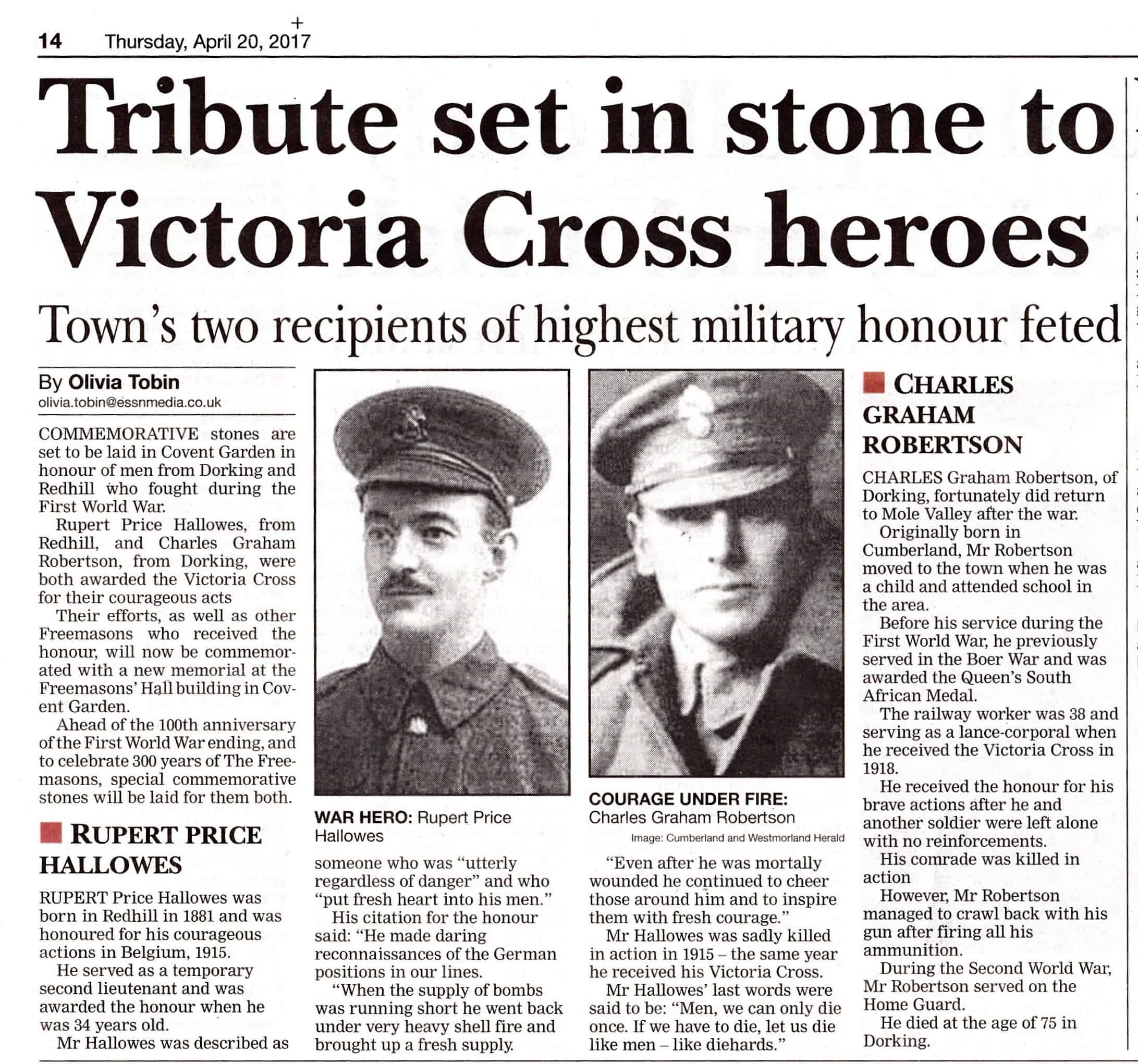

With the onset of the Great War, Charles enlisted in the 10th Battalion, The Royal Fusiliers on 7th September 1915 and arrived at the Western Front in November 1915. He was wounded in April 1917 at the Battle of Arras but returned to his battalion in time to take part in a raid on the night of 31st August/1st September 1917, for which he was awarded the Military Medal.

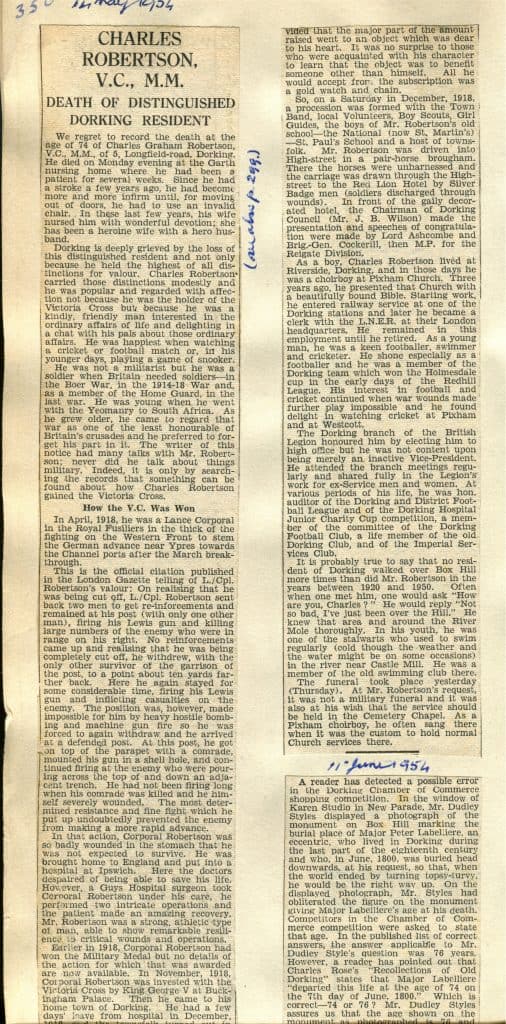

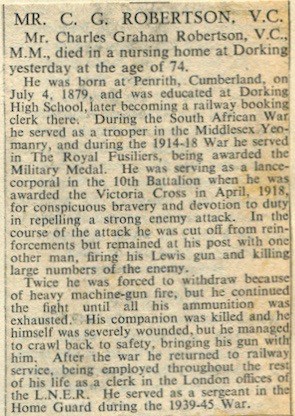

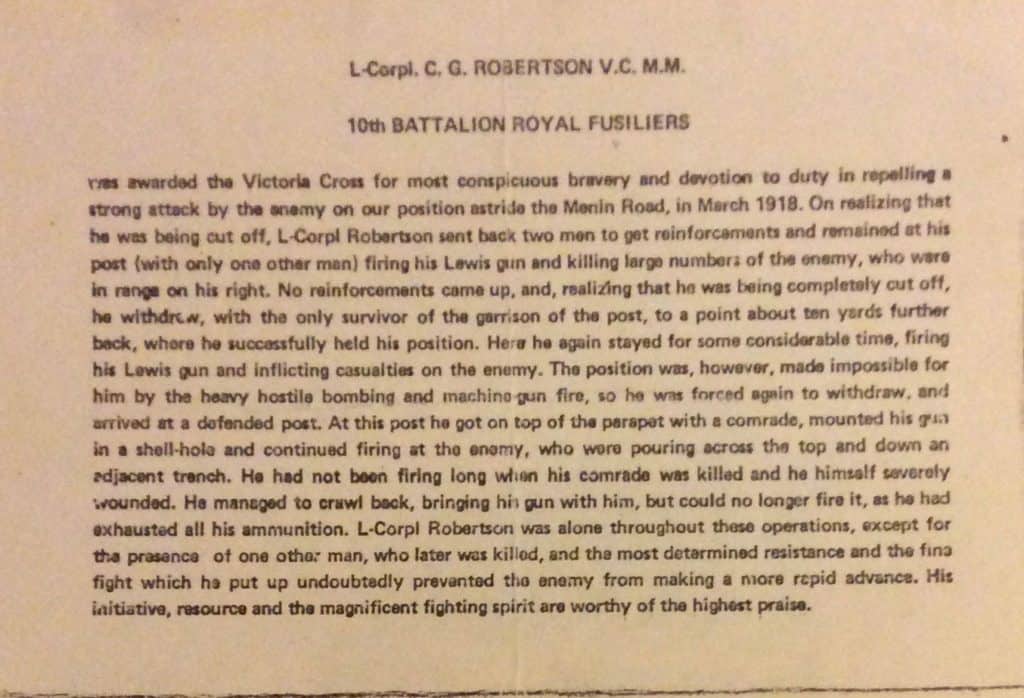

In early 1918 he found himself in the thick of the fighting to stem the German advance near Ypres after the March breakthrough known as the Kaiser’s Offensive. Further progress would have seen the Germans reach the Channel ports, with disastrous consequences. Robertson repelled a strong German attack on his position. Realising he was about to be cut off, he sent two men for reinforcements whilst he and another held the position, firing his Lewis gun at the advancing Germans. No reinforcements arrived but Robertson continued to hold the position, firing alone when his companion was killed. Twice he had to move further back but he continued to fight, though wounded and under heavy machine gun fire, until his ammunition was exhausted. Without his actions the Germans would have been able to make a much more swift advance in his sector.

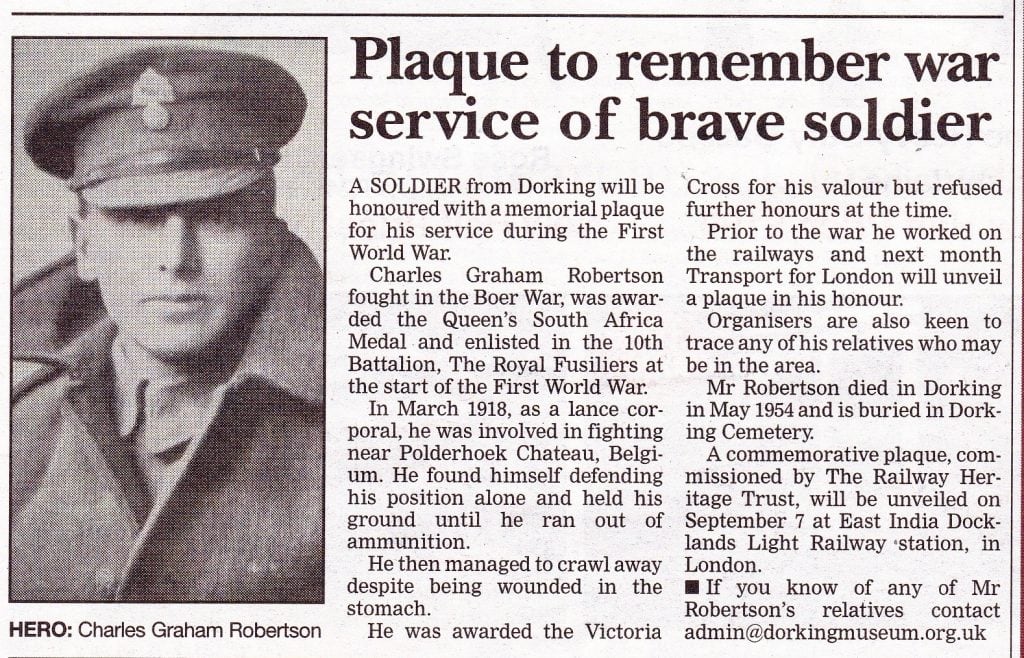

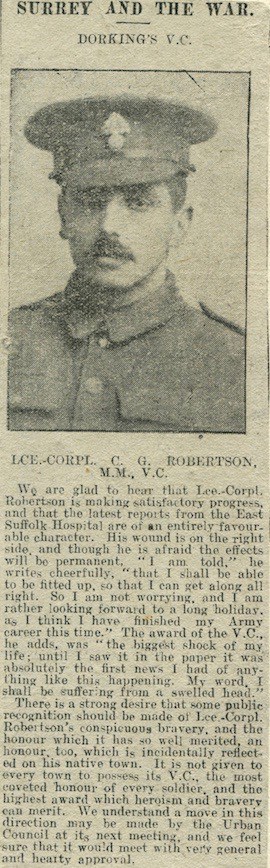

Wounded in the stomach, Robertson was not expected to survive. But after being evacuated to England and undergoing intricate surgery, he made an unexpected recovery. On 5th April the London Gazette announced that he had been awarded the Victoria Cross. On 20th April the Dorking & Leatherhead Advertiser reported him writing from his hospital bed that it was ‘the biggest shock of my life’. ‘My word,’ he wrote, ‘I shall be suffering from a swelled head’.

‘There is a strong desire that some public recognition should be made’, said the paper, claiming that the honour was reflected on his native town. ‘It is not given to every town to possess its VC.’

Dorking Urban District Council undertook a public collection to raise funds that the town might honour him. But Robertson rejected any ‘fuss’. He agreed to accept a gold watch and chain but asked that any other monies raised be put to charitable use. In December 1918, after his presentation with his medal at Buckingham Palace, thousands turned out to see Lance Corporal Robertson presented with his watch. He was brought by horse-drawn carriage to the High Street in procession with Boy Scouts, Girl Guides, school children, and the town band. At the High Street the horses were un-harnessed and the carriage was drawn to the Red Lion inn by Silver Badge soldiers (who had been discharged from service through injury). At the Red Lion, decorated in red, white and blue, Lord Ashcombe and the local MP made speeches and Robertson was presented with his watch.

After the war, Charles resumed work at the Great Eastern Railway, retiring in 1939. It seems that his half-sister, Eleanor Draycott, may have lived with Charles and his uncle in Rothes Road during the 1930s. In 1939, when he was 60, Charles married Doreen Madeline Gascoigne, aged 39. During the Second World War, he was a sergeant in the Home Guard. He played an active part in Dorking town institutions and enjoyed watching cricket or football, playing snooker and walking on Box Hill.

Charles Robertson died in Dorking in May 1954 and is buried in Dorking Cemetery.

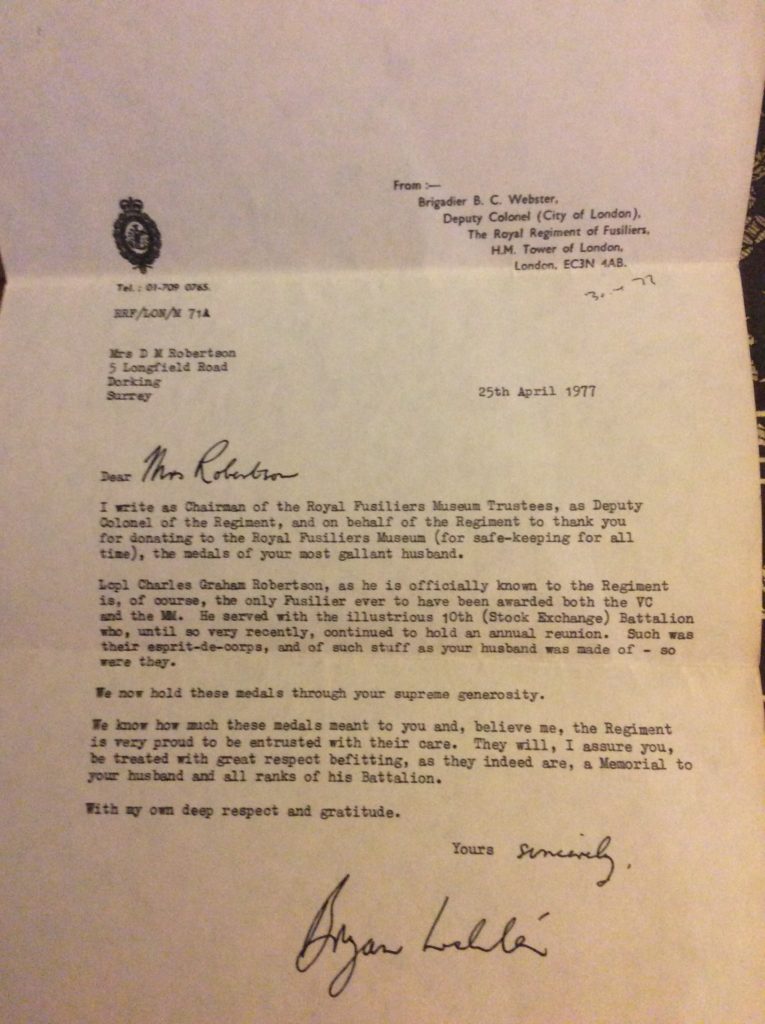

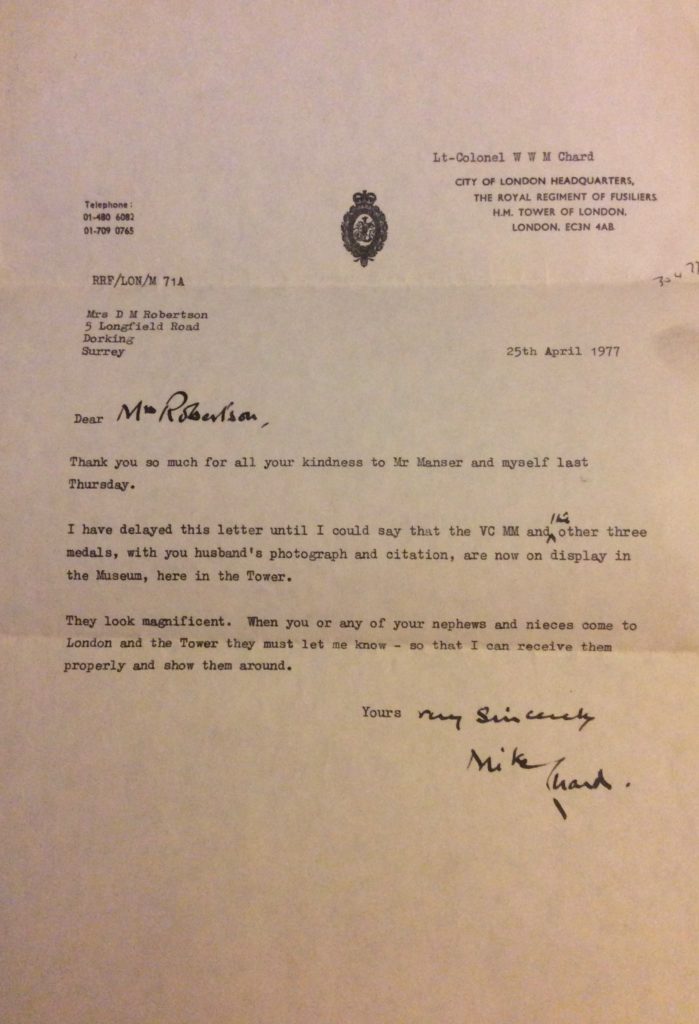

His Victoria Cross is displayed at the Royal Fusiliers Museum in the Tower of London. This and his other medals were presented to the museum by his widow in 1977. In May 2017, the Museum was contacted by Elizabeth Graham Potts, a relative of Charles, who sent copies of the correspondence between the Royal Fusiliers Museum and Charles’ wife.

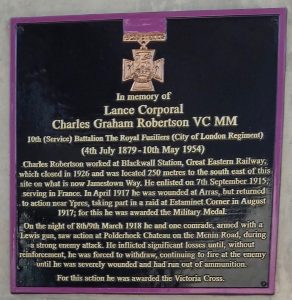

On 7th September 2015 the Railway Heritage Trust unveiled a commemorative plaque at East India Docklands Light Railway station, in London. The date was exactly 100 years to the day that Charles enlisted in the Army.

A Transport for London spokesman said, “We were pleased to be working with The Railway Heritage Trust which commissioned a memorial plaque to commemorate the bravery of Lance Corporal Charles Graham Robertson VC. This is just one of a series of plaque unveilings which will ensure that the seven railway staff whose outstanding bravery led to them winning the Victoria Cross are suitably commemorated by the industry.”