The question of how to commemorate the dead began even before the war ended. The involvement of the whole nation in the conflict and the introduction of conscription had changed attitudes. Politicians realised that statues of military commanders would not convince the public that the sacrifices of ordinary people had been recognised.

National memorials were funded by the government. Money for local memorials had to be raised by public collections from families, friends and colleagues. So widely were the effects of the war felt that villages, churches, schools and voluntary organisations all raised money to install their own crosses, plaques, and memorial windows.

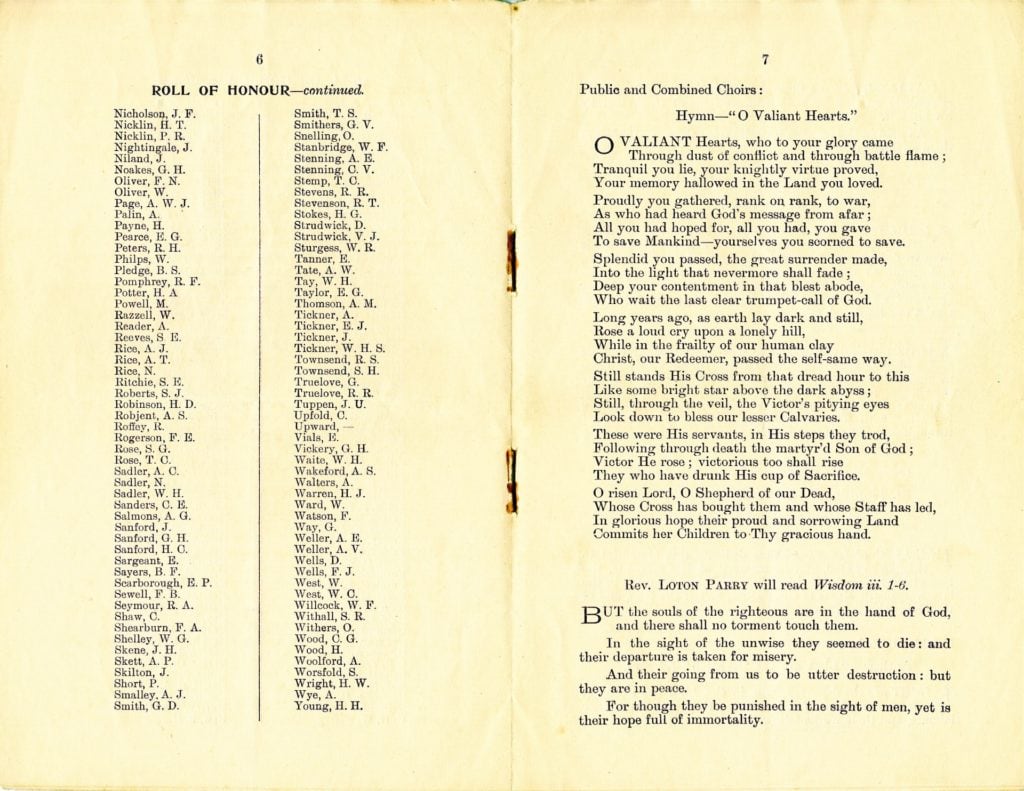

It was initially proposed that Dorking’s ‘roll of honour’ should recognise not just those who died but all who had served or who had done war work, including women. But in the end it was only the male dead whose contribution was recorded.

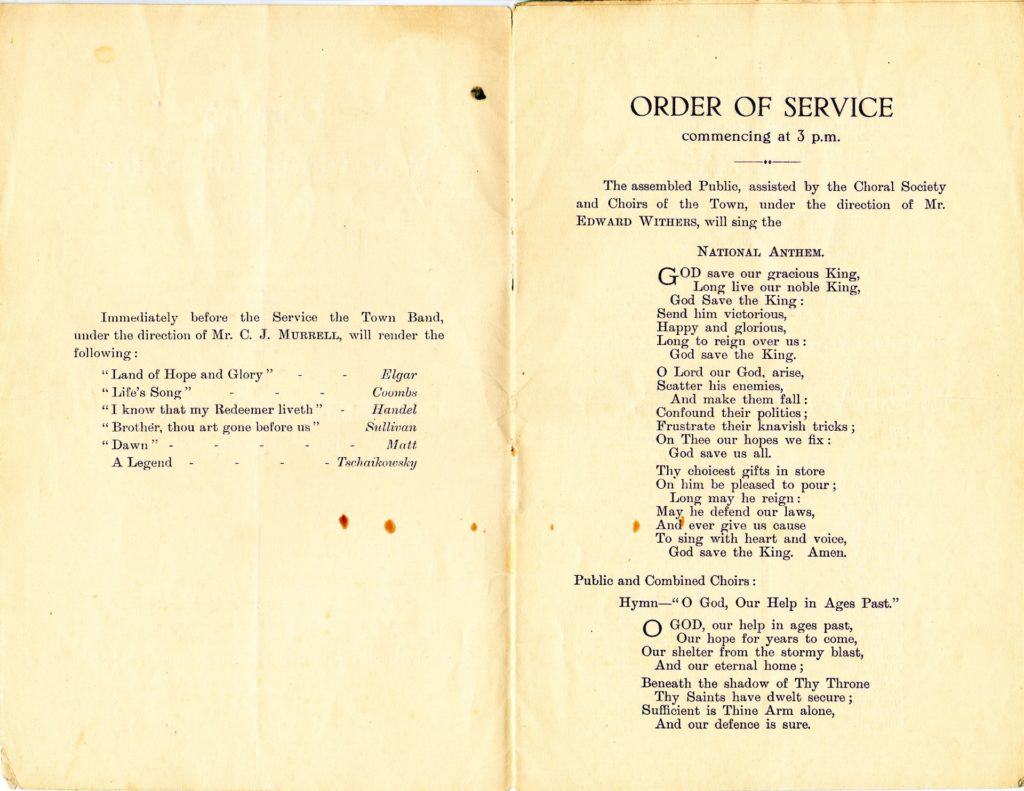

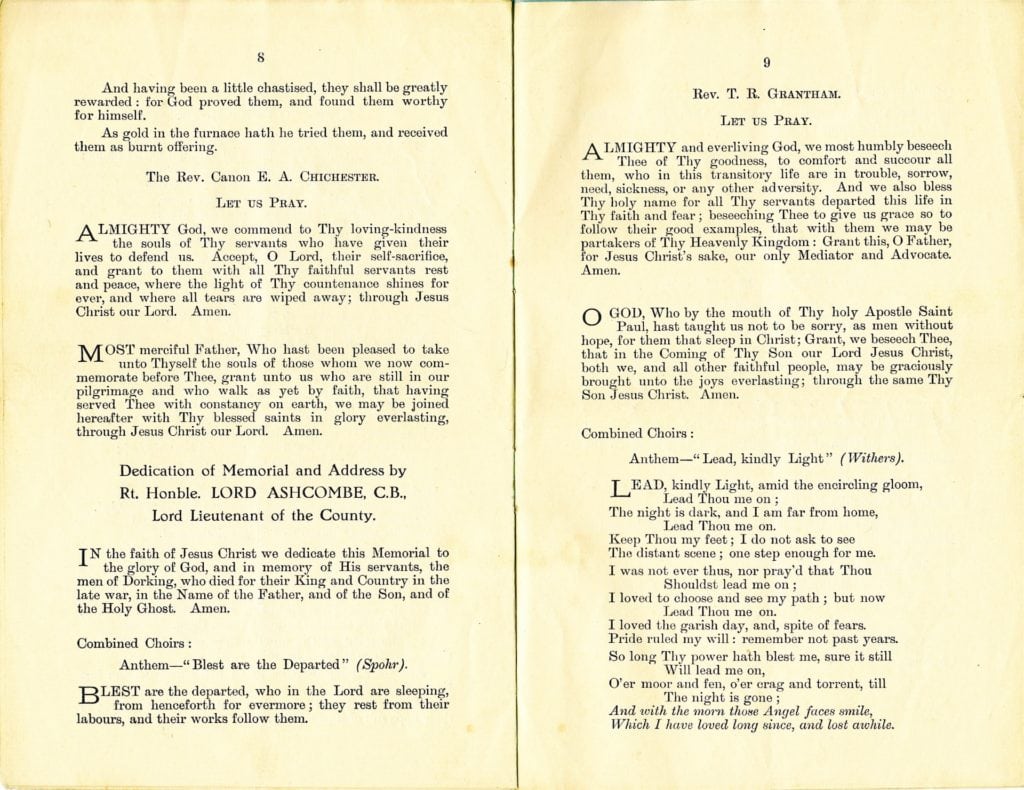

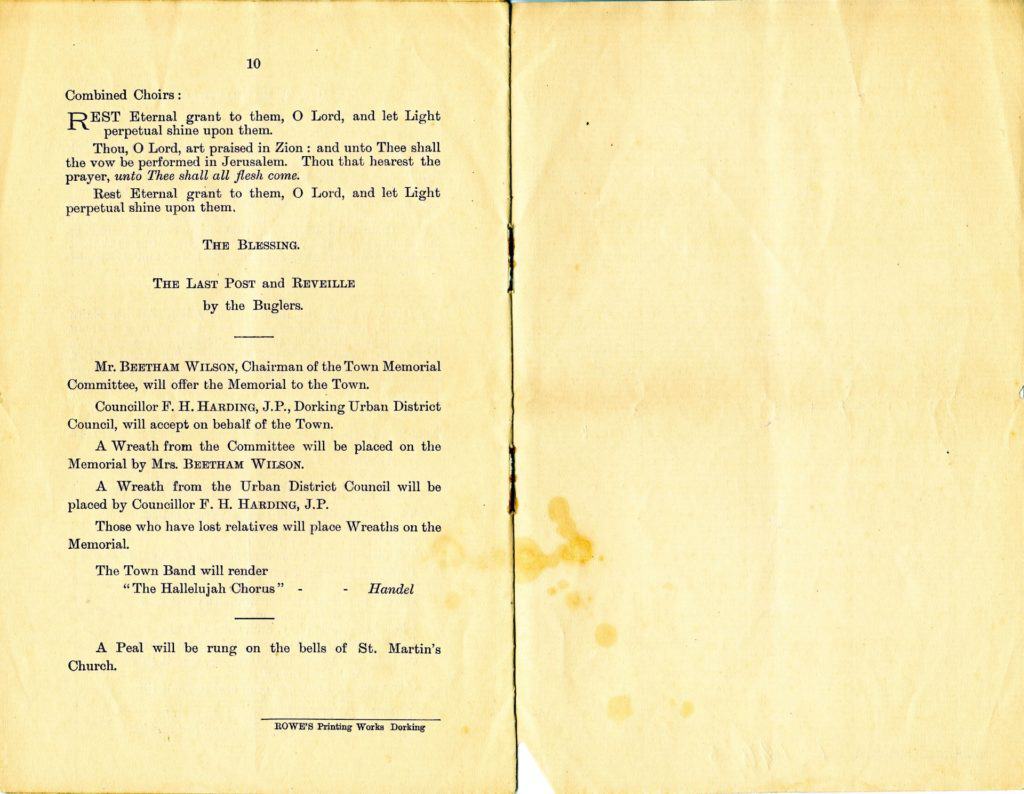

Dorking war memorial was unveiled on 17th July 1921, the anniversary of the first peace celebrations. A crowd of 3,000 gathered to watch.

How many men did the Dorking area lose?

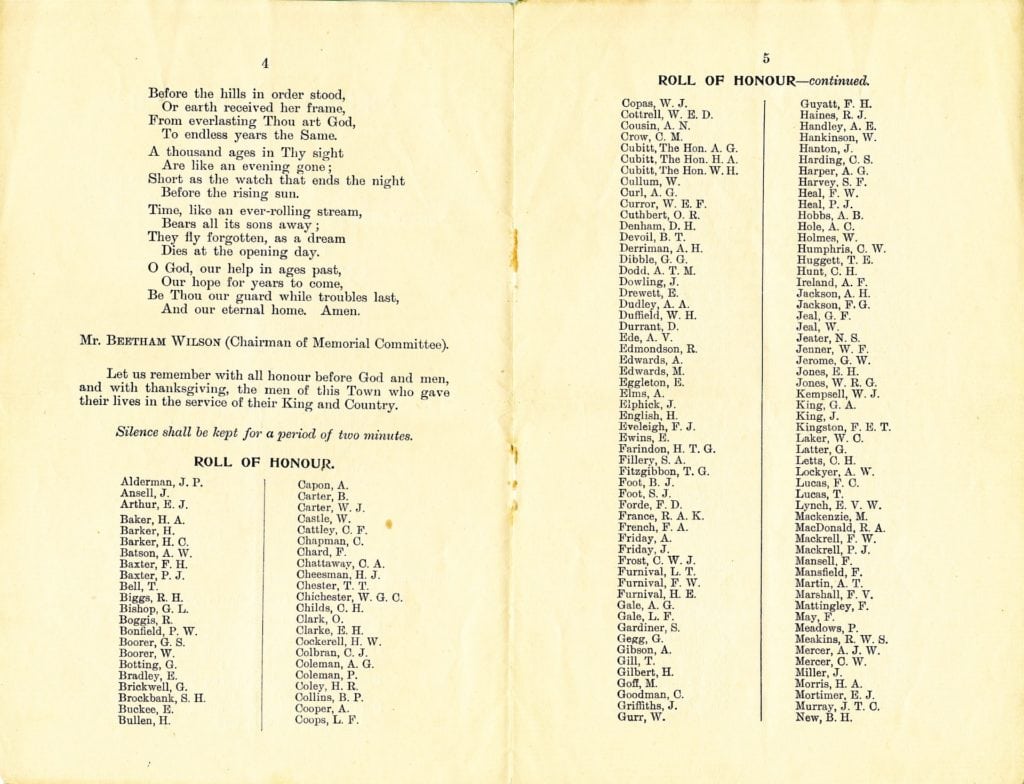

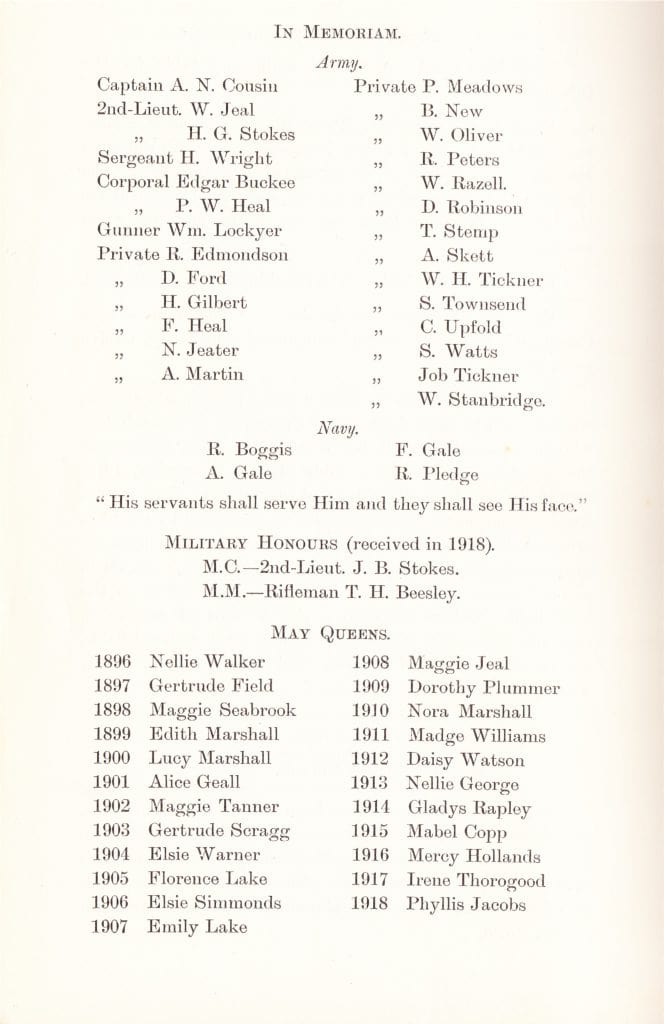

The town memorial lists 269 casualties. Adding those listed on village and other memorials takes the tally to nearly 900. But record keeping was ad hoc and inaccurate, with overlaps and omissions and different criteria applied for inclusion from village to village. In some the fallen had to have grown up in the village; in others the link could be tenuous. Some of those recorded spent little, if any time in the village concerned; others who spent their lives in a particular place are absent from the memorial. Some of the fallen – particularly the wealthy – are commemorated on multiple memorials; others – and all of those who died of their injuries after 1920 – are not commemorated anywhere. And at least one man on the Dorking memorial, Reginald Boggis, was not dead at all!

Despite the death of at least three women whilst undertaking war work, the only woman to appear on a local memorial is Grace King of Abinger.

The memorial records the names, not just of those who were killed in action, but those who died in any circumstance, whether by accident, suicide, illness or disease, whilst on service. The names are not ordered by rank, the sons of lords sit alongside those of labourers. This recognition of the equality of sacrifice of the private soldier and the officer emerged from the experience of a war which had broken down class barriers.

War Memorial Dedication Programme

The day of the unveiling was oppressively hot and the town band played ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ before a hail storm moved in, bringing the first rain in over two months. The atmosphere would have been emotional: most of those attending would have had direct links to someone whose name is on the memorial. Lord Ashcombe and Canon Chichester, who officiated, had both lost sons. The bandstand behind the memorial was dedicated by Charles Edmund Hall to his fellow townsmen who had died.

The Dorking British School roll of honour, 1918. The juxtaposition of the names of the old boys of the school who had been killed with their contemporary May Queens is poignant. The school’s own memorial proudly celebrated ‘the splendid devotion and heroic sacrifice of the lads who unhesitatingly gave themselves at their country’s call’. There is no sense of disquiet that the boys’ education should have been for this; such doubts were seldom expressed in the post-war years of relief and national celebration

Families often paid for public memorials to perpetuate the memory of those they had lost. ‘Dead Man’s Penny’ memorial plaques were issued to the next-of-kin. The family of Hugo Molesworth Legge, who grew up at Holmwood Lodge in North Holmwood, set his into a pew at St John’s church to create a public memorial.

The bus shelter and dovecot in Westcott were erected in memory of Boyd Burnet Geake, whose mother and father lived on Coast Hill. Wealthy families installed brass plaques or tablets in churches and schools, or, like that of John Lee Steere of Jayes Park in Ockley, dedicated village halls or other amenities to the memory of the lost.

The memorial window to Leopold Grieg Heath was installed at Christ Church, Coldharbour by his parents Arthur and Flora Heath of Kitlands. The window is unusual in depicting troops in contemporary battle dress, worshipping with the blasted landscape of the battlefield in the background.

The memorial panel to Henry Harman Young by James Powell & Son in St Martin’s Church, Dorking, depicts St George, the patron saint of England. Such imagery was common and sought to place the war and those who had fought in it into a recognisable and comforting cultural narrative of moral certainty and heroism.

Henry Cubitt, 2nd Lord Ashcombe, and his wife, Maud Marianne nee Calvert, lost three of their six sons to the war: Henry Archibald Cubitt, Alick George Cubitt and William Hugh Cubitt. The boys’ cousin, William George Cubitt Chichester was also killed. The memorial chapel at St Barnabas’ on Ranmore is their memorial. A plaque in memory of 11 other parishioners of Denbies and Ranmore who were killed was dedicated in 1922.

Symbolic murals by E Reginald Frampton depict the values for which the war was supposed to have been fought: faith, hope and charity, peace, justice and fortitude. The patron saints of England, France and Belgium are shown in armour defending these values like knights of old. The spirit of 1914 was perpetuated in such language and imagery which provided comfort to bereaved families, affirming that the deaths of their loved ones had not been in vain.

The wealthy had the funds to commemorate their losses in public and the abundance of their memorials contributes to the myth of a ‘Lost Generation’. The Cubitt family’s losses are still remembered today, those of the Newnham family of Wotton, who lost John, Albert and Noel, and the Furnival family of Westcott, who lost Frederick, Harold and Leonard, are not.

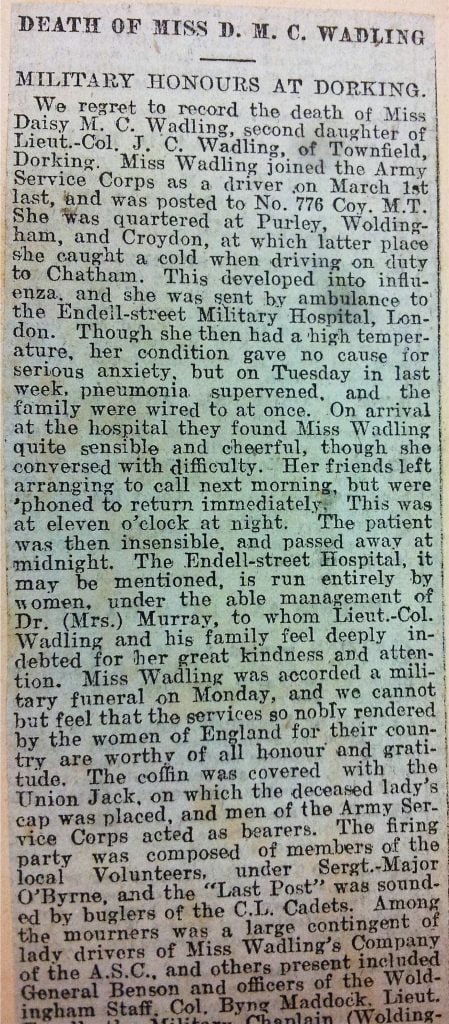

And one who is not on a memorial – Miss Daisy Wadling’s military funeral

In September 1918 Daisy Wadling of ‘Townfield’ received a full military funeral at Dorking cemetery. She was driving for the Army Service Corps when she contracted influenza which turned to pneumonia. Daisy died at the Endell Street Military Hospital in London’s Covent Garden, which was run by ex-suffragette doctors.

Her body was returned to her family in Dorking. At her funeral her coffin was covered with a Union Flag and carried, with her military cap on top, to the cemetery by ASC bearers. After the funeral service a firing party of local volunteers fired in salute.

It would have gratified the women of Endell Street to see the local paper comment that: ‘We cannot but feel that the services so nobly rendered by the women of England for their country are worthy of all honour and gratitude.’ The very fact that a military funeral could be held for a woman in a small market town indicates the changes in women’s lives, and in acceptance for their emancipation, that the war had brought. Unlike men doing similar roles who died of disease whilst on service, however, Daisy’s name does not appear on any war memorial.

Last : Celebration

Next : Evolution or revolution