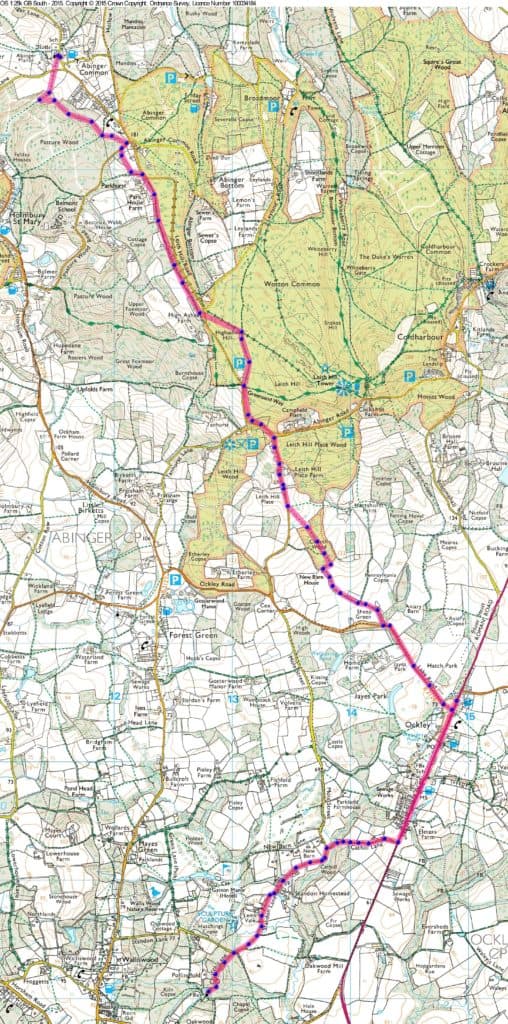

We have been publishing the Abinger Monthly Records for a few issues now. We came across this walk, from the October 1889 edition, which Jackie and Mick Rance from the Museum walks team have plotted out for the website.

The original walk would have followed the tracks over Leith Hill, which are now roads. To avoid walking along the edge of these roads, we have followed footpaths. We can’t avoid the stretch along Stane Street – but there is a pavement to walk along.

The walk is 12.5kms with 365 metres elevation and is point to point.

From the Abinger Monthly Record October 1889

An ardent lover of rural scenery and of strong antiquarian tastes, I found myself on a recent occasion among the charmingly wooded and heather clad hills of the hundred of Wotton Surrey, which for diversified and picturesque scenery, stands unrivalled in the whole county.

Having visited the ancient and interesting chantry, so romantically perched on the rising slope of a dark briar-tangled glen in the deep recess of an ancient forest of Okewood on the northern confines of the Surrey Weald, and which contains so much of interest to the antiquary, I made the best of my way to Ockley, which possesses one the prettiest villages I have ever seen, in the centre being the very picturesque well, erected in 1837 in accordance with the will of an Ockley governess, who left all her money for the beneficent purpose of providing the villagers with a good supply of pure water.

Passing along the old Roman Road, known as the Stane Street causeway, that skirts the eastern boundary of the Green – on the south side of which, according to the old Saxon Chronicle [1] , a sanguinary battle was fought in the year 851 between the Saxon forces under King Ethelwulf, and the invading Vikings from Denmark, in which the latter were utterly routed- my thoughts naturally reverted to those stirring scenes of the olden time.

Time did not permit of a stroll to the churchyard [St. Margaret’s Church at Ockley] to see if the custom mentioned by Camden “of planting rose-trees upon the graves especially of young men and maids who have lost their lovers“ [2] still prevails; so after a very brief rest at “The King’s Arms”, I resumed my journey along the Stane Street Causeway, “lined with noble oaks and leafy chestnuts,” to the roadway leading up the “wild rough heights of Leith Hill,” passing on the way Jayes Park (the residence for generations of the ancient family of Lee Steere) and Leith Hill Place (the home of the Wedgwood family of pottery celebrity).

My object being a visit to Abinger Church, which, from my reading of that famous volume – so dear to the topographer and historian – the ‘Domesday Book’, compiled by order of William the Conqueror in 1086, I had become aware, gloried in the possession of a genuine old Saxon Church; I hastened on quickly, missing no doubt many a fine view from a certain vantage points on the road. An uphill walk of an hour or so landed me on the plateau of Leith Hill, carpeted with heather and bright bilberry bushes, called in this neighbourhood hirts or whortleberries, the fruit of which is much prized by the cottagers, and whose lamentations this year on the almost utter failure of the crop are both loud and long. The heather being in full bloom presented a glorious sight, reminding me of the happy days of boyhood spent on the bleak, wild, upland moors of my native “north countrie”.

CC BY-SA 2.0

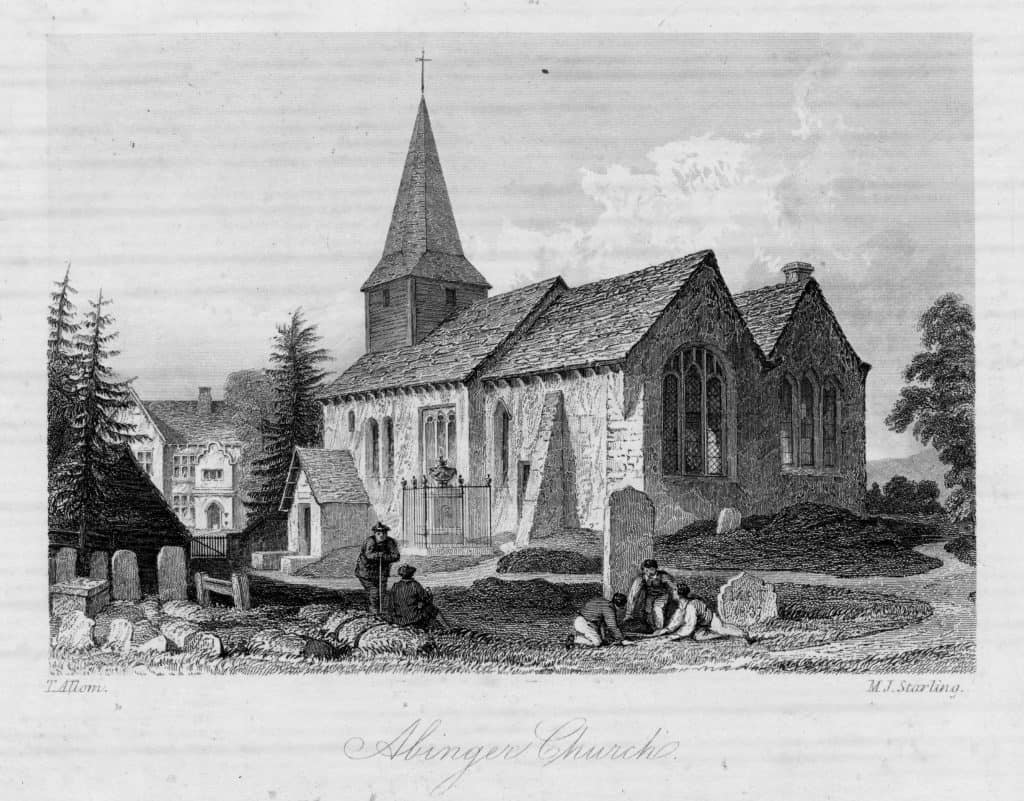

After passing Abinger Common, with its fine healthy “Wellingtonia” – planted on the greensward opposite the village post office, some twenty odd years ago (as an obliging peasant proudly informed me), by the Lord of the Manor, and protected by an iron fencing – I soon came within view of the church. The first sight was not by any means prepossessing. The hand of that modern Vandal, yclept the church-restorer, is so painfully perceptible, even at a distance, that no casual visitor passing this way would ever dream that there stands a building whose foundations were planted in all probability a thousand years ago; at any rate anterior to the Norman Conquest. Stepping over the stone style by the side of the picturesque modern lych-gate, I thought of those beautiful in Gray’s ‘Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard’ :-

“Beneath those rugged elms, that yew tree’s shade,

Where heaves the turf in many a mouldering heap,

Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.”

© Dorking Museum K3

[1] “The same year (A. D. 851) came three hundred and fifty ships into the mouth of the Thames, the crew of which went upon land and stormed Canterbury and London, putting to flight Bertulf, King of the Mercians, with his army; and then marched southward over the Thames into Surrey. Here Ethelwulf and his son Ethelbald at the head of the West Saxon army, fought with them at Ockley” (spelt Aclea in the old Chronicle), “ and made the greatest slaughter of the heathen army that we have ever heard reported to this present day. There also they obtained the Victory.”

(Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ingram’s Translation, pp. 92-93)

The Chronicle mentions two synods having been held at Aclea :- “A.D. 782. The same year there was a synod at Acley.” “A.D. 789. This year there was a synod assembled at Acley.” Spelman in his ‘Councils and Ecclesiastical Documents,’ pp. 439, 465, gives the place at which these two synods were held as uncertain, so that Ockley cannot lay the same claim to them as it can to the battle-field.

[2] 1673-1692 Ockley (published 1718)

In the Church-yard are many Red Rose-Trees planted among the Graves, which have been there beyond Man’s Memory. The Sweetheart (Male or Female) plants Roses at the Head of the Grave of the Lover deceased; a Maid that lost her Dear 20 Years since, yearly hath the Grave new turf’d, and continues yet unmarried.

Aubrey, John, The Natural History and Antiquities of the County of Surrey [1673-1692], vol. 4, (1718), pp. 185-186

1695

Ockley (Sussex) where is a certain custom, observed time out of mind, of planting rose-trees upon the graves, especially by the young men and maids who have lost their loves; so that this churchyard is now full of them.

Camden’s Britannia, 1695 (Gibson edition), col 162; 1722 edition, vol. 1, p. 183 [This is not in earlier editions of Camden. Both Evelyn and Aubrey (above) contributed to Gibson’s edition of Britannia.]