Dorking’s most famous dinosaur, Baryonyx (also known as Claws), is a puzzle because nobody is sure what he or she really looked like. All the reconstructions we see of Baryonyx in various books are down to the interpretations of the artists. We only have the skeleton and some fish scales to go on, though we do know it prowled around a tropical swamp. We can use these clues to, at least, make an informed guess. The rest is down to your interpretation.

The way the bones fit together show us the basic shape of the creature. Its pointed teeth tell us it was a meat eater (a carnivore) not a cuddly vegetarian (herbivore) with bad breath. It was well suited for grabbing fish and, perhaps, snatched them up with its giant claws, rather like a grizzly bear does today. Years after Baryonyx was discovered, some bones of an Iguanodon dinosaur were found with a Baryonyx tooth nearby. Maybe Claws was also a scavenger or just munched anything he or she could lay claws on.

What about the skin? Was it rough or smooth? Most paintings show Baryonyx with a smooth skin, but perhaps it had a rough surface like a crocodile. Some modern reptiles, like the bearded dragon, have colourful skin adornments to attract a mate. Maybe Claws displayed ‘dino-bling’ (as in our own depiction on page 6 of the book).

Could Baryonyx have had feathers? It certainly couldn’t fly, but could it have used fluffy feathers for warmth or display, like some other dinosaurs – including T-Rex.

What about its colour? We can look at today’s animals for clues. Some use camouflage to make themselves blend in to hide or help them make a surprise attack. Others have bright display colours so they can show off to potential mates (just like a peacock or a kingfisher). What about stripes (like a zebra) or spots (like a leopard)?

Look at photos of today’s animals in books or on the internet, then make a painting of your idea of what a living Baryonyx might really have looked like. Be bold and creative, then explain your ideas.

The tale of the wrong sea monster!

This is the story of how a new fossil sea monster was found in Dorking Museum.

Museum people don’t like to mention this, but sometimes specimens in museum collections are not what they seem. Some old labels are quite simply wrong. That goes for the world’s top museums.

Marine reptile expert, Dr Roger Benson of Oxford University, didn’t make himself the most popular man in the world when he came to Dorking Museum and found that an extinct sea creature, discovered in a local chalk quarry, had been wrongly identified.

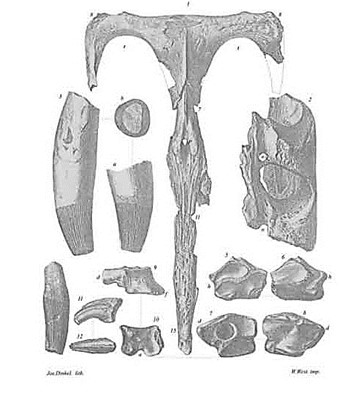

The man who originally named the fossil in 1858 was none other than the famous Richard Owen, founder of London’s Natural History Museum and inventor of the word Dinosaur! Owen was one of the top experts of his day – the ‘go-to’ guy when it came to fossils. He had carefully studied the remains of the creature after being contacted by Lord Ashcombe who owned the chalk quarry in Dorking where the specimens were found. The shapes and arrangement of the bones told him it wasn’t a dinosaur, rather the remains of a giant marine reptile, known as a pliosaur, that swam around in a vast prehistoric ocean where Dorking lies today.

He gave the creature the grand scientific name: Polyptychodon interruptus.

Admittedly, he only had a few bones to go on and the study of fossil marine reptiles (and dinosaurs) was very much in its infancy.

A century and a half later, in stepped Dr Benson. A lot of what we know about the prehistoric world has changed since Owen‘s time. Dr Benson had been studying fossil marine reptiles all over the world and, when he came to examine the specimen in Dorking Museum, he realised it was very similar to specimens found in America which had already been classified under a different name: Brachauchenius.

He also knew that specimens of Polyptychodon found in different locations had lived millions of years earlier than the Dorking specimen.

Oops! Given how little anyone knew about extinct reptiles in 1858, it is hardly surprising that Owen was mistaken, but it means that the Dorking pliosaur has now been reclassified as a Brachauchenius – which makes it a new fossil for Dorking Museum!

Dorking Museum’s former Chairman, Nigel Arch, saw the positive side. Commenting on Dr Benson’s visit, he stated that the Dorking specimen was:

“a good example of the value of our collections and the fact that we can always learn more. It is wonderful to think that the study of this specimen, found locally and collected by a local person, is still contributing to scientific knowledge today.”

This is what museum collections are for.