By 1830 desperate men were living on hills and commons, surviving through crime. Anger at lack of work and low wages was directed at the town authorities – largely insulated against the poverty of the countryside by virtue of their London interests.

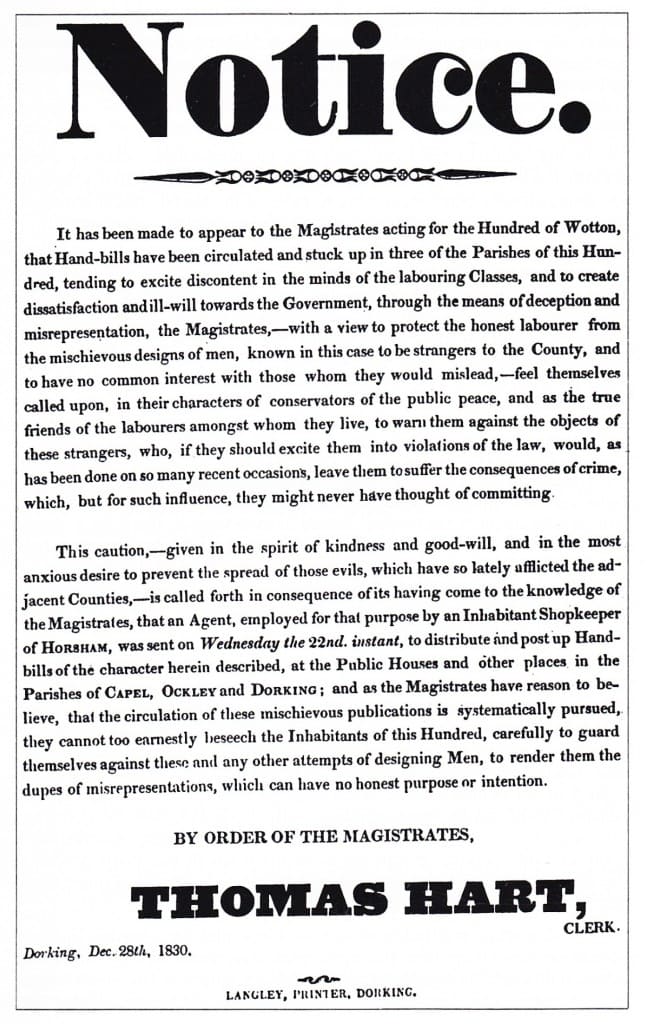

In November 1830 labourers ran through Dorking shouting ‘bread or blood!’ Haystacks were burned at Trouts Farm, Ockley, and a mob gathered at the Wotton Hatch. On 22nd November Dorking magistrates asked for the cavalry to be quartered in town. The authorities took staves into the Red Lion and burned pikes to prevent them being used by rioters. Townsmen swore in 114 special constables. Hundreds stormed the town. As magistrate James Broadwood appealed to the crowd outside the Red Lion a riderless horse appeared, packed with broomsticks. Rioters seized the sticks and attacked the hotel before being chased out of town by the cavalry.

The influential writings of Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) may have influenced the parish authorities in their decision to encourage emigration. Born at the Rookery in Westcott, Malthus’s Essays on Population (1798-1826) proposed that poverty was inevitable as population would always increase more rapidly than the means of subsistence. He concluded that poverty and misery were necessary to keep population growth in check.

The painting depicts a family leaving poverty-stricken Abinger for a new country. Emigration from the Dorking district continued into the 20th century with the emigration of a group from Wotton in 1903.

In the spring of 1832 the Dorking Emigration scheme arranged for 72 people to join a ship bound for Canada. The parish had concluded that the land would never support all those available to work. Two years later when the poor relief was further reduced [again] magistrate Charles Barclay was burned in effigy.

It was immigration rather than emigration that eventually alleviated Dorking’s poverty. As the beauties of the area became [grew] renowned the well-to-do moved in, bringing employment in their mansions, villas and gardens. They brought incomes from other activities, their estate farms subsidized by trading, brewing or banking. By the late 1830s Dorking was acclaimed a London in miniature ‘possessing shops little inferior in taste… to those of Cheapside and the Strand’.

Last : The Country Estates

Next : Poverty and the Workhouse