The transition to peace was hard. Food was scarce and people were tired. Some of those listed on local war memorials succumbed to the influenza epidemic of 1918 which killed more people worldwide than the war. James Still of Westcott and his wife Olive died within two days of one another, leaving their son an orphan at three months.

War-related hardship continued well after the war. Far from finding themselves favoured by employers over those who had not volunteered as local landowners had promised in 1914, those returning with injuries often found that they could get no work and conscription and the passage of time had blurred memories of who had gone voluntarily.

Disabled survivors were a reminder for decades of the effects of industrial warfare. The maimed and the dying depended on charity to pay medical bills and ambulance fees when they went for treatment. The death toll continued to climb as died as a result of their injuries into the late 1920s.

The death or incapacity of bread-winners plunged whole families into poverty. Widows struggled to bring up families alone and often the only option was to re-marry. Charities bought school uniforms and paid apprenticeship fees for orphans and paid for boots and clothing for the children of disabled fathers. The Emergency Fund was still making payments to those whose financial hardship was attributable to the war into the 1930s, enabling widows and the wounded to buy groceries and coal.

With no universal health care system, the war raised questions in the minds of many as to the contract between the citizen who found himself called upon to fight in time of crisis but was little supported by the state in his resultant adversity. But it would take another war for those issues to be fully examined and addressed.

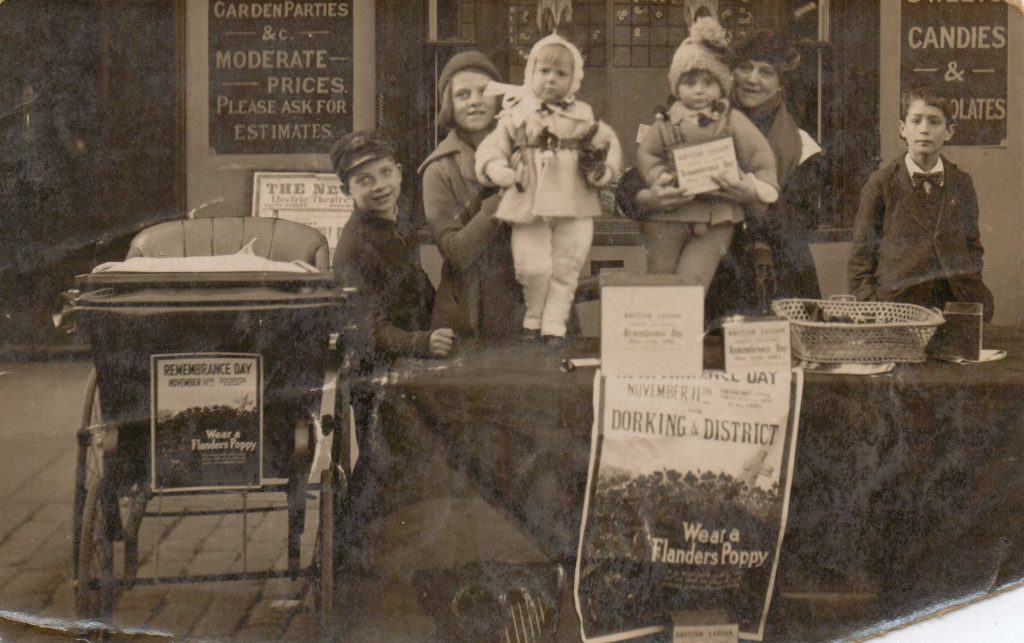

The British Legion was formed in 1921 to provide support and to raise funds for ex-servicemen.

William Collins had worked as a gamekeeper on the High Ashurst Estate on Box Hill before the war. When he was killed his wife Laura and their four children were evicted from their home which was tied to William’s job.

Albert Sadler was a labourer who lived in Falkland Road with his wife and two children His wife Frances remarried within six months of his death. Such quick remarriages were not unusual and were often prompted by economic necessity. It is a myth that there was a generation of women who were unable to marry after the war; in fact the marriage rate went up in the post-war years.

Noelle Campbell-Stewart of North Holmwood lost her first husband, William George, in 1915. In 1917 she married Humfrey Kennedy, who was killed in 1918. Her third husband was Humfrey’s brother.

There were many applications to town and village charitable funds in the 1920s as veterans sought to re-establish civilian lives and find employment. But in was impossible to find work for all: in 1924 the Dorking Emergency Fund was unable to find training for work which could be undertaken by one-armed Mr Jordan who could not afford boots for his children and who, according to his doctors, needed ‘expensive apparatus’ for his leg and arm.

Last : Evolution or revolution