Stories from both sides of the wartime divide

The Holmbury Hill German prisoner of war camp

Until Beattie Ede revealed her childhood memories to a local historian 70 years after the war, few people were aware that Holmbury Hill was used as a prisoner of war camp for Germans.

Today you can explore the Holmbury Hill prisoner of war trail for yourself.

Why was Holmbury chosen as the site for a prisoner of war camp?

Holmbury Hill was, and still is, covered in forest and a continuous supply of timber was urgently needed for Britain’s war effort, as timber was used as pit props in the coal mines and to hold up the trenches. With most of the local men away fighting, there was a severe shortage of labour.

Germans taken prisoners of war were not forced to work, but they were offered the chance to earn some money by felling trees. Whether or not they were aware, their efforts were desperately needed.

From August 1917 until the end of the war in 1918, small gangs of POWs worked with cross-cut saws (which took two men to operate) to cut down trees.

Horses pulled the timber away to be loaded onto a narrow-gauge railway. The timber-laden wagons used gravity (controlled by an elaborate chain mechanism) to make the descent of half a mile or so to the sawmill, then the power of heavy horses to pull them back up again.

Holmbury Hill gets very bleak in the winter, so it must have been tough having to live and work there twenty-four hours a day. When it snows, blizzards whip up into deep snowdrifts. In high winds, trees snap like matchsticks and pine debris lies everywhere.

We can only speculate what life at the camp must have been like. The few official documents record it in a positive light. The POWs were said to have been well-clothed and kept warm. No-one tried to escape. At least the POWs were safe out of the war – and they were fed.

But what really went through the minds of the prisoners when they arrived back at the camp in the evenings? Did any of them write letters home to their families or keep diaries? Did they hear the bells of St Mary’s Church on a Sunday morning?

One night, after the war came to an end, they quietly left for home and the camp was abandoned.

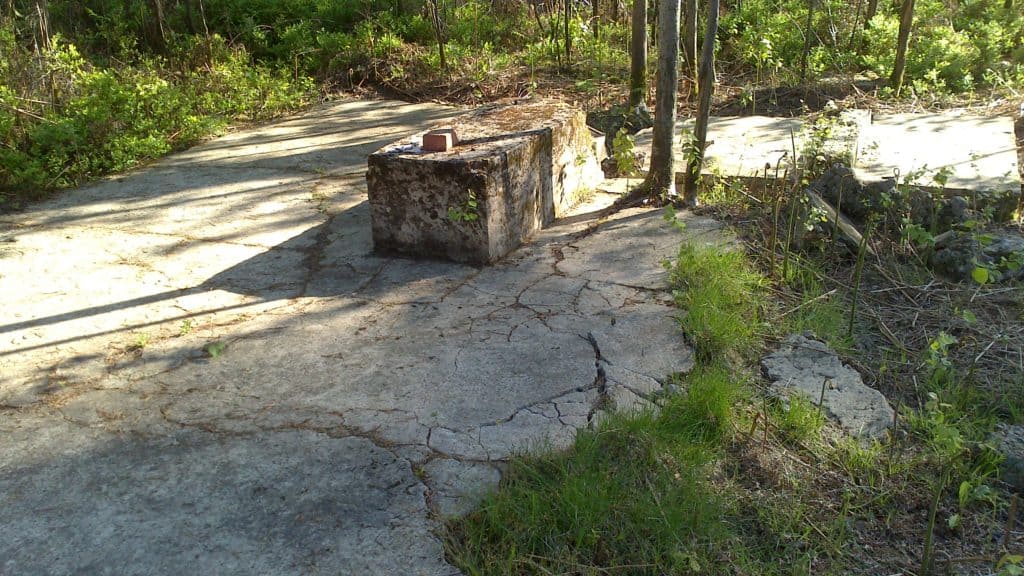

Nobody knows who the prisoners were. Today, the concrete bases of the buildings – which are gradually being overgrown by the forest – are all that remain to tell the tale. Perhaps, one day, someone from Germany, tracing their family history, will throw further light on this story.

Read the full Surrey Archaeological Society 2013 report about the Holmbury POW camp.

The woman on the Abinger war memorial

War memorials remind us of those who lost their lives serving their King and country. Dorking Museum’s War Memorials Project traced the true stories behind the names on all our local war memorials. Take a closer look at the war memorials in your area and you will see familiar family names because many of the relatives and descendants of the listed names still live here.

Listed on the war memorial on the village green at Abinger Common is Grace King.

Grace served as a nurse at the Cantine des Anglais close to the British front line.

As well as the explosions and the bullets, disease was rife because of the filthy, rat-infested conditions on the battlefront.

Grace died in Paris of an unspecified illness (possibly typhoid or typhus) in 1917 at the age of 24.

Her grave at St James’ Church, Abinger, reads: ‘A soldiers grave the best for thee’.

Many brave women served in similar roles, but Grace is the only woman listed on any of the war memorials in the Dorking area.

Find the stories behind the names on your local war memorial.

War in the trenches

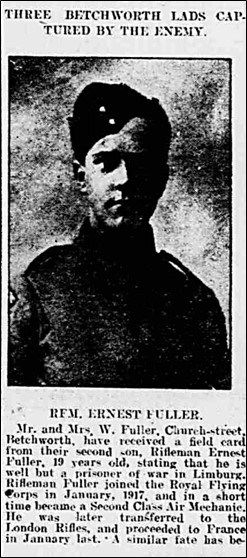

A 19 year-old soldier from Betchworth found himself caught up in a firefight at the height of a battle in France. His platoon was helplessly surrounded and many of his fellow soldiers were killed in the attack.

Rifleman, Ernest Fuller, was captured and made prisoner of war. He was taken away and forced to work deep underground in the iron mines until the war ended.

When he eventually returned home, he wrote a rare account of his terrible experiences. What he and his friends went through is almost too painful to bear.

Below you can read extracts from his eyewitness account of trench warfare and being taken prisoner of war

MY CAPTURE, EXPERIENCE AND TREATMENT WHILE IN GERMANY

Description of warfare in the trenches of France, 1918

About 4.30 on the morning of the 21st the Bosch (what British soldiers called the German soldiers) started a very heavy bombardment and of course our people too, but we seemed to have very few guns on our front and the Bosch had the fog and smoke from the gun fire all to his advantage.

Well, we were awaiting orders in support line and had to take cover the best we could find, for three of us there was a little bivey, a shelter let in the trench of sand-bags, and corrugated iron with dirt and rubbish over the top. While sitting under there in an uncomfortable position, my Chum got a piece of shrapnel in his boot, but never touched his foot and soon after that I could not say what happened, but I found two Corporals were pulling the sandbags, dirt and corrugated iron off us, and I was so tangled up that they had to cut off my equipment and gas-mask to release me, and when they got my chum and me out the third fellow had unfortunately got his back broken, I don’t know what happened to him, but they took us two and put us in a dug-out, and it was a difficult job to get there for shells were falling in all directions. We had to keep down and every now and again do a duck and run. Finally, we got there and found this dug-out nearly full of wounded, who had been put in there for safety. The doorway was half a curtain and the other half was thick sleepers, so I crouched up behind them, and the shells were falling just outside the door, we expected to be blown up every minute. But no, the barrage passed over, and one fellow was going to see if he could find some rations but he had to return and with the sad news that the Germans had surrounded us, had captured our Battalion’s Head quarters, and were waiting outside for us, with a few stick-bombs in each hand. They called to us to come out. About eight of us got out.

Capture as a prisoner of war

When the Germans were waiting for us, of course there was no hope of escaping, so we had to go. As we went over the trench which was all blown to pieces, most of us got a good hit in the back with the butt of the Bosch’s rifle, that was the beginning of our cruel treatment. We were taken over the barbed wire and through their trenches up to our neck in mud and water.

We got back after a struggle, some little distance after coming through a lot of shells which were being sent over our people, still we got through without being injured, to a deep dug-out, where the Germans questioned us and took away our over-coats and anything else that was good to them.

After keeping us there some little time, they took us back to a small village where we found some more prisoners. They then got us altogether and marched us back to another larger village in the afternoon. The sun was fairly hot and it was a long way, and we could not stop. When we got there, we were again questioned and turned into an open-air cage with barbed wire very thick and high.

After 24 hours with nothing to eat they gave us a small piece of black bread and something like coffee. We stayed there two nights and it was very cold and we had just a few yards to walk about in to keep warm, and we got so tired we slept in the day time when it was warm. After spending two nights there, we were removed again. After walking three hours to the Station, we were put in cattle wagons early in the afternoon of the 23rd and arrived about 9 in the evening at a much larger place where there were 5,000 prisoners, and three large open cages. We spent three nights there again in the open and bitter cold and rain, with no overcoats. The last night there we were given a spade or two between 500 men to dig a bit of a hole to get in out of the wind. For one day’s food we got a piece of dry black bread, about six in the morning, and coffee, and at four in the afternoon, a pint or so of field cabbage all boiled up in water, or Swedes or anything rotten.

While I was there several poor fellows died, who were wounded or could not stand the cold and exposure.

Put to work in the mines

Arrived at Homecourt on the same day, about nine miles from Metz. Here we had to work in iron mines, 300 feet below the earth, and it was very cold and the work was hard. Two prisoners had to load twelve two-ton wagons a day. We had to start in the morning at 6.30, on a piece of dry bread, and come up in the afternoon at 4.30. If our work was done, if not, we had to stop down until it was, and with nothing to eat all the time we were down the mine, and when we did come up and get it, it was only a lot of mixed up dried cabbage, Swedes and stuff, which it was sometimes impossible to eat, and we were always starving hungry. There were always a lot of sick, but you had to be nearly dead, and when you went before the doctor you had to look out or you got a good whack on the side of the head or on both sides. We all had fever of some description and could not eat anything. One fellow went away to hospital and died, and another Italian died in camp. There were 150 at this camp, 100 Italians, and 50 English.

Moved on

We had to go to a place called Dornton. We had about mile to walk to our camp. When we got there we found a gravel pit where we had to work in. Our camp was on the edge of the pit so we never had far to walk, only we always had to work in all weathers. One day when we were all working, one of the heads came round and picked out six of us to go and work in the mine, about a mile away, and I was one of the unlucky ones. So I had to start in another mine on the next Monday. Three of us had to work by day and the others at night. The work there was not quite so hard, but the mine was a rotten one, as the water was always dripping and everything was always wet and greasy. While we were there the Germans told us all sorts of things – that there was a revolution in England and that they were starving at home, and I don’t know what, still, we never took any notice.

Rifleman Fuller’s full account of his wartime experiences is kept in the Dorking Museum archives.