© Dorking Advertiser

The writer George Meredith lived and wrote at Flint Cottage at the bottom of the Zig Zag Road on Box Hill. He first came to Mickleham on a walking trip and married local girl Marie Vulliamy at St Michael’s Church in 1864. He wrote in a two-room chalet in the garden, often sleeping and eating there. Flint Cottage was visited by Thomas Hardy, Algernon Swinburne, Robert Louis Stevenson, Oscar Wilde, George Bernard Shaw, George Gissing, James Barrie and HG Wells. When the cottage was full visitors stayed at the Burford Bridge Hotel.

Meredith’s work was radical, particularly in its treatment of women. Modern Love (1862) has been called the first ‘modern’ poem. Diana of the Crossways (1885), set at Crossways Farm in Abinger, fictionalises the struggle of Caroline Norton (grand-daughter of playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan of Polesden Lacey) for a settlement on the breakdown of her marriage. In his old age he became known for his support for the vote for women and amongst his local circle were pioneering female foreign correspondent Flora Shaw of Little Parkhurst in Abinger and the suffragette Brackenbury women of Peaslake. He corresponded with the Leith Hill and District Women’s Suffrage Society and wrote to The Times in support of Holmwood suffragette Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence when she was imprisoned in 1906.

Meredith celebrated the Box Hill countryside in verse and used it as a backdrop to his fiction. When no longer able to walk the hill he was pulled in a bath chair by a donkey called Picnic.

Image E5. 19 © Dorking Museum

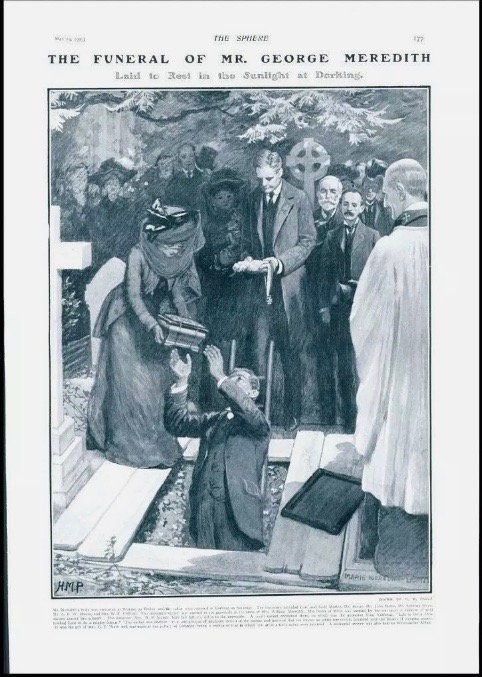

Because of his religious unorthodoxy Meredith was denied burial at Westminster Abbey. He is buried in Dorking cemetery. Autograph hunters pursued the London literati who turned out for Meredith’s funeral at Dorking Cemetery.

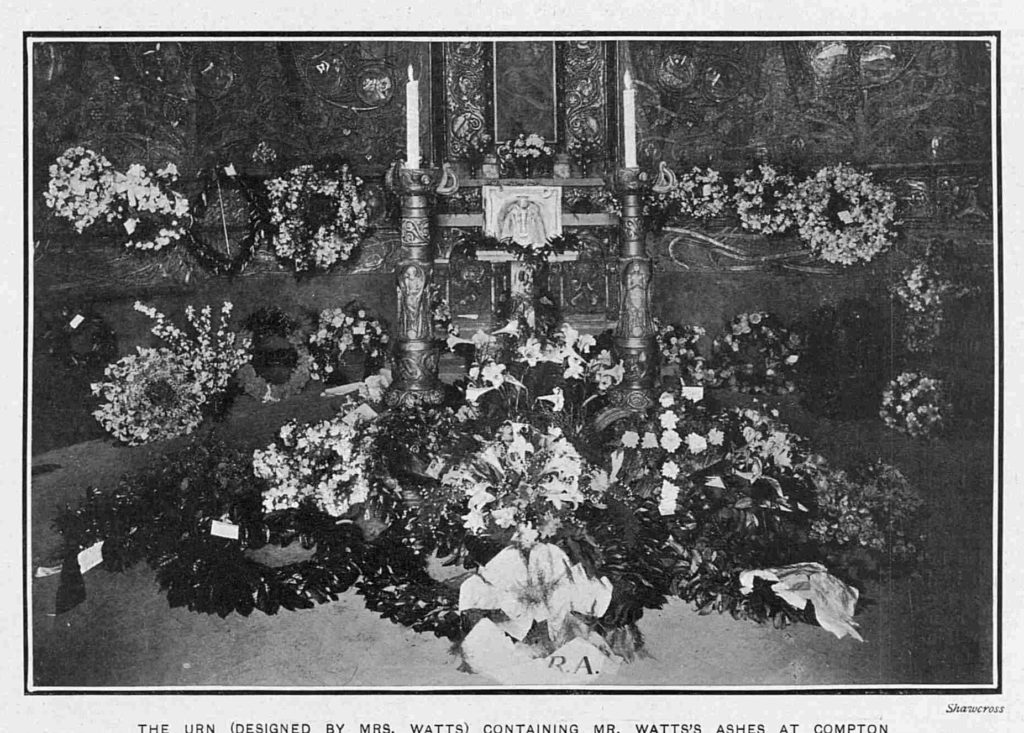

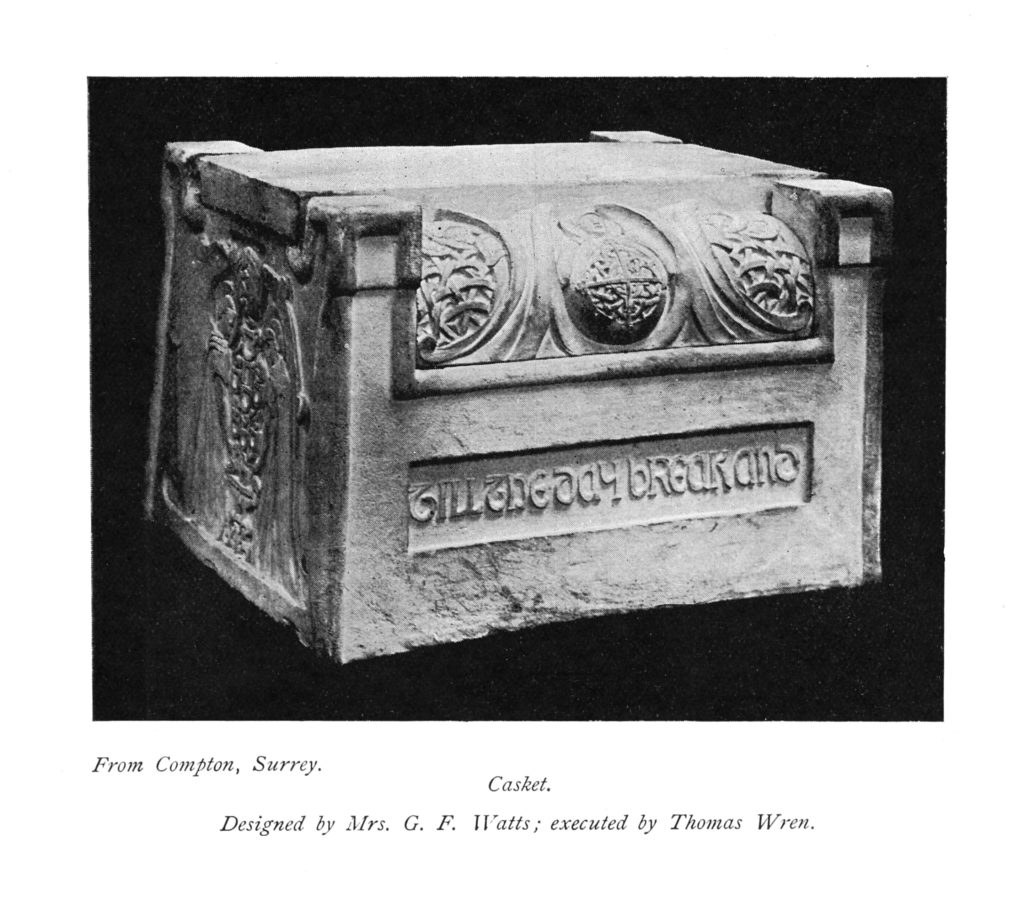

Dr. Louise Boreham (Co author of Mary Seton Watts and the Compton Pottery with Hilary Calvert) contacted us, as she was interested in the casket containing his ashes.

She wrote “I found an illustration which states that it was donated by Mrs G. F. Watts & made at her Compton Pottery.

The attached illustration mentions that the casket was the same design as the one Mrs Watts designed for her husband, G F Watts, but in the newspaper article and the drawing from The Sphere, they are definitely not the same. So, I wondered if the artist in my article was using artistic licence, but if your museum image is a photograph, then there is a bit of a mystery! Both Mr & Mrs Watts were enthusiastic admirers of the writings of George Meredith, so it would have been in keeping for her to have donated the casket.

Image © The Sphere

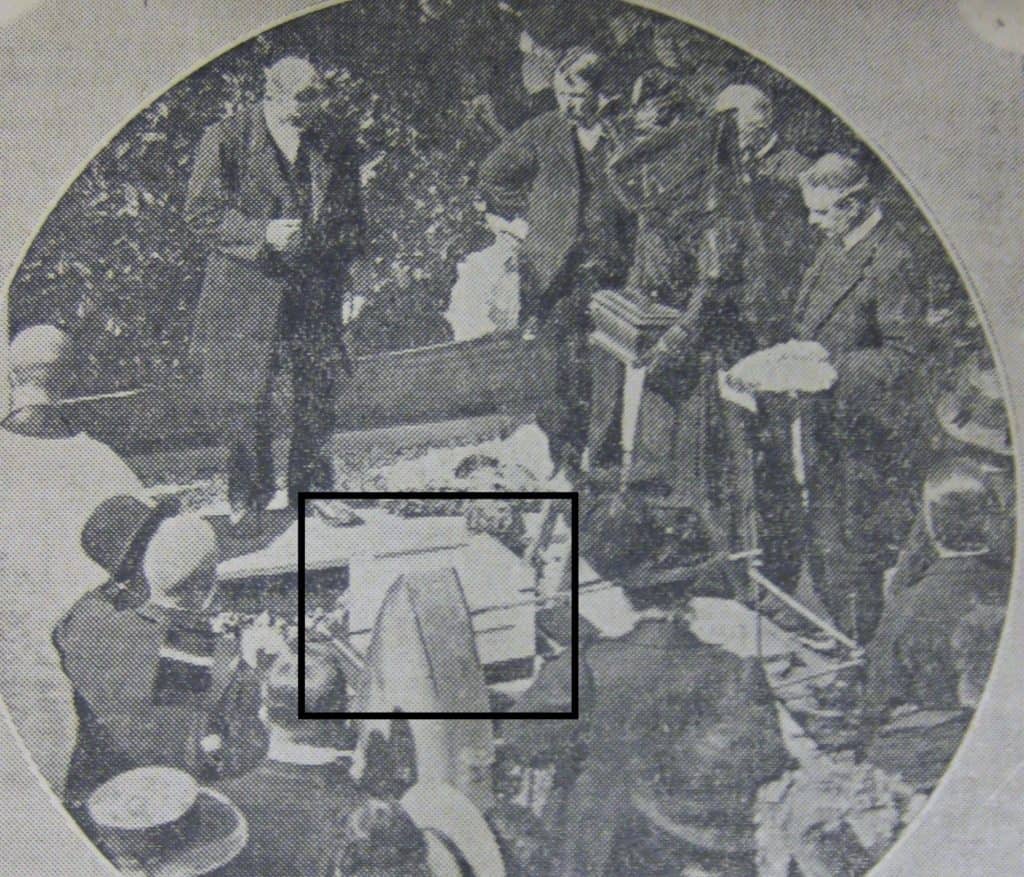

We looked a little closer at our image – the veiled lady on the right of the newspaper cutting picture is holding a casket. And it looks very like the one in the illustration and not at all like the Watts one in the picture. It looked as if the artist had used a photograph of the actual funeral as a base for his drawing. So it would appear that what is being placed in the grave is not a Compton casket.

However Dr. Boreham spotted the Compton terracotta cinerary casket in the newspaper image. “To the left of the ladder and in front of the pointed gravestone is a square white rectangular shape, which I now realise is the casket. I compared it to the design, with the weeping angels on each end, published in the Art Journal in 1904, in my view, the terracotta casket design is the same. I now realise that the it was actually placed ready on top of George Meredith’s open grave, ready to receive the casket containing his ashes held by his daughter. So, the painting, which appeared in the Sphere, did not accurately reflect the scene in the cemetery, where one of the gravediggers is shown standing on the ladder about to receive the casket from Mrs Sturgis, with no sign of the terracotta one.

Exhibition of Home Arts and Industries’ Art Journal, 1903, p.218.

My co-author of ‘Mary Seton Watts and the Compton Pottery’, Hilary Calvert, wrote about George Meredith’s funeral on pp. 172,173, which includes the photo of the casket from the Art Journal.”

Extract from Hilary Calvert & Louise Boreham Mary Seton Watts and the Compton Pottery 2019, Compton, Guildford, ch.9, pp.172-173

Cinerary caskets were made to hold cremated ashes but were not illustrated in the Pottery catalogues. One example, inscribed ‘Till the day break and shadows flee away’, was exhibited at the 1903 Home Arts and Industries exhibition and illustrated in the 1903 Art Journal. It was also described in the catalogue of the Modern Celtic Art of Garden Pottery Exhibition at the Grafton Gallery, Bond Street in 1904.[i]

George Watts was an advocate of cremation, considering it a more sanitary form of disposal for a fast-growing population. The first crematorium in Great Britain had opened at Woking, Surrey in 1895, and by his wish he was cremated there following his death in 1904. His ashes in their white terracotta casket rested on the altar at the Compton Mortuary Chapel and were then interred in the grave outside the cloisters.

On 22nd May 1909 the cremated ashes of George Meredith, a then-famous author, were interred at Dorking Cemetery. His daughter, Mrs H P Sturgis, whose family were friends of the Wattses, carried the ashes to the grave in a small wooden casket. The New York Times said: ‘The casket was enclosed in a sarcophagus of exquisite design of white terracotta molded with figures of weeping angels. It was a replica of that in which the great artist’s ashes were interred’ and had been given by Mrs Watts.

[i] Archive of Art & Design, Victoria & Albert Museum.

Further information on the Compton Pottery can be found in the book “Mary Seton Watts and the Compton Pottery“.