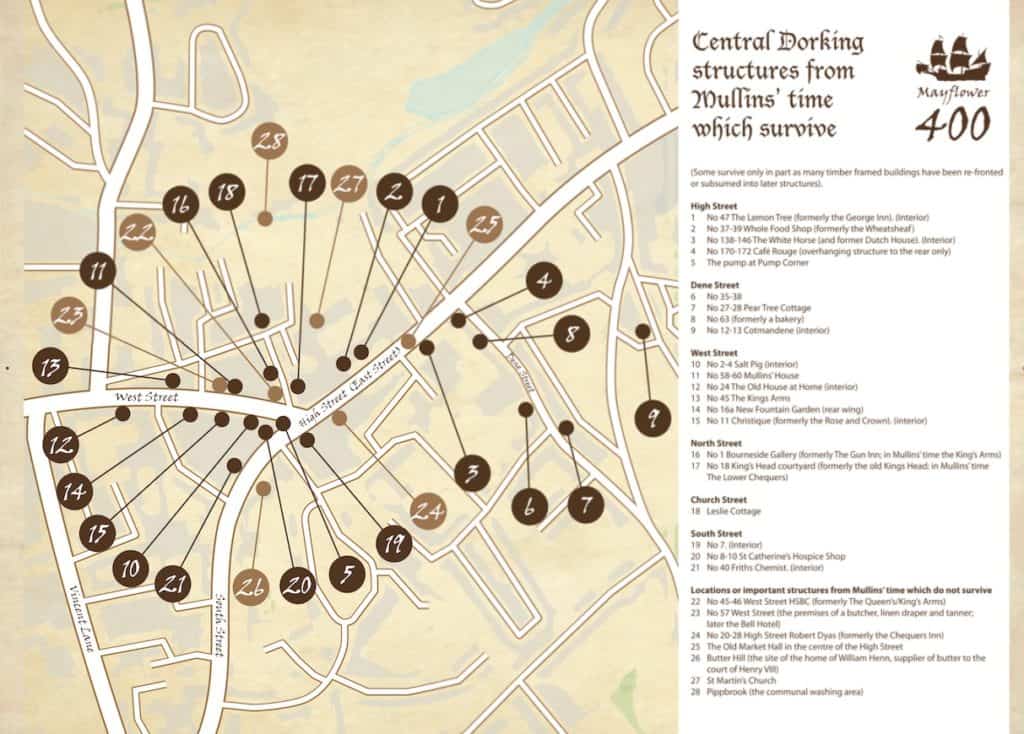

A number of houses from the early 1600s survive in Dorking and many business premises have their origins in buildings that would have been known to the travellers on the Mayflower. Buildings were timber-framed with roofs of Horsham stone. Timber came from Holmwood and other local woods. The oak was used within a year of felling, before the wood became too hard to work.

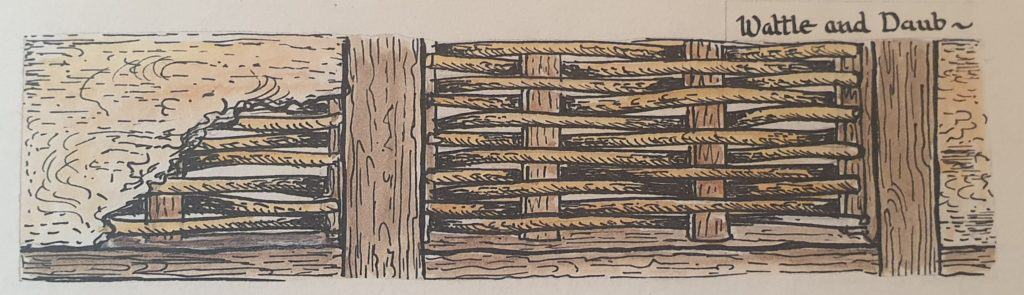

Walls were made by weaving lathes into panels and covering them with a mixture of clay, dung, straw and water, a technique known as ‘wattle and daub’. Though there was plenty of clay to the south of the town, brick making was a laborious process and therefore expensive. Clay had to be dug, tempered for months, shaped and dried in the sun. Only the wealthy could afford brick infills for their walls.

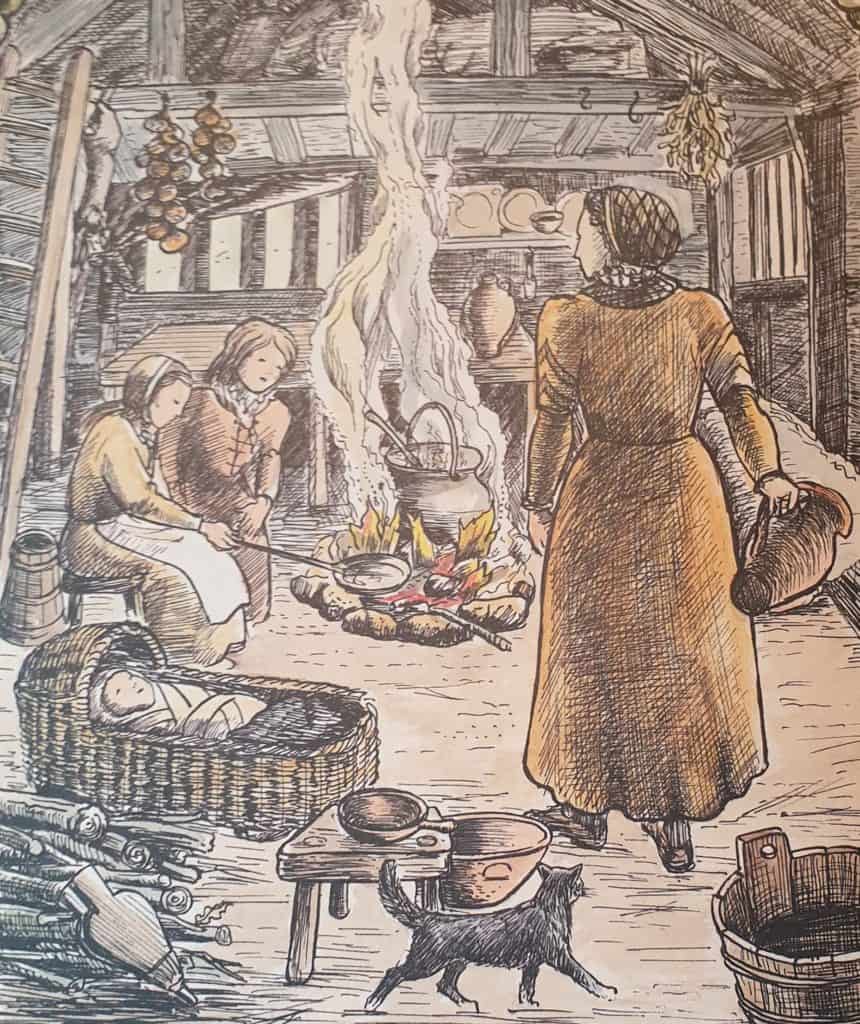

Most houses in the town were single storey dwellings with small unglazed windows and a central fire. Smoke escaped through the roof. Floors were earthen and covered in rushes. Higher quality houses had a large open hall with a fire in the middle, service rooms at one end and an upper storey at the other.

In the years before 1620 many of Dorking’s older buildings were improved and extended. Single storey properties had an upper storey added. Open fires were boxed into ‘smoke-bays’ which took smoke out of the living area via a bay where meat and fish were hung to smoke. Communal open halls were divided to create private rooms. Glass became more affordable and as bricks became more readily available chimneys took smoke clear of roofs. During this period the house owned by William Mullins was renovated, rebuilding an earlier structure on the site. After the works it would have been one of the town’s most prestigious buildings.

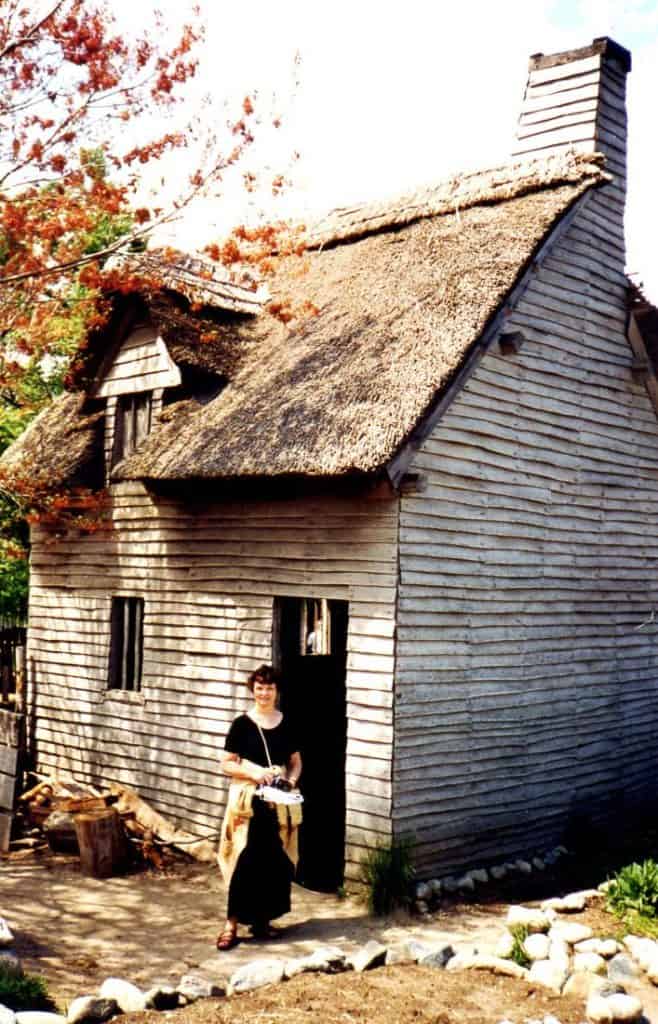

On arrival in America the colonists built their first houses in winter. They were small, with one room and a storage loft. Local trees provided the timber for frames similar to those the settlers had known in England, but the roofs were thatched with grasses and reeds from the marshes. Thinly sliced wooden clapboard panels were attached to the outside walls to weather-proof them. Peter Browne’s house still survives at the Plimoth/Patuxet museums. Later Browne and Priscilla Mullins and her husband moved out of Plimoth to the settlement of Duxbury where they built more spacious homes. The Alden House Museum website in Dubury has a virtual tour of the some of the houses.

All Photographs by Royston Williamson

To construct ‘wattle and daub’ walls lathes were placed into slots in the house beams and hazel rods were woven into a basketlike structure. Sheep’s wool was mixed with the daub to prevent it cracking as it dried and a lime plaster was applied over the top.

Wooden framed houses were assembled like a jigsaw to a plan. Each beam and support was labelled with assembly marks to indicate its place. The timbers were held together with oak pegs. As the oak dried it would shrink and move and then harden into a strong frame. Because oak must be worked whilst it is still green buildings can be dated to within a year of construction by analysis of tree rings in their timbers.

Stone-built St Martin’s Church would have been the biggest and most prestigious building in the town. The only church for many miles, it was probably built in the 12th century and is where the Mullins family would have been required to worship – and fined if they did not.

It is thought to date from the early 1600s.

A hall house with a central fire. The fire was essential for warmth and cooking. By the early 1600s many of Dorking’s early houses were being remodelled with the addition of narrow smoke bays which took the smoke up through a channel, making houses much less smoky.

Previously : Shoes

Next : Food and Farming