An edited version of the talk given on 11 September 2014 by Nigel Arch, Chairman of Dorking Museum

There are now very few people alive who can claim to have clear memories of the Great War. The last fighting Tommy died some years ago and the sons and daughters of the soldiers who fought and died are very old. My late father in law, born in 1915, remembered the first words he heard as “wounded soldiers”. Our connection with that war is through the material artefacts it produced: letters home, medals and faded photographs. It is also through the art and poetry that the war produced- vivid testimony to the catastrophe that engulfed the world between 1914 and 1918. Perhaps above all, in this centenary year of its outbreak , a reflective mood is induced by the contemplation of the memorials, national, local and family, which were erected in the years after the war. Dorking Museum is commemorating the Great War through the medium of a series of exhibitions that focus on the Home Front. It is also placing on its website an extraordinary tribute: the details of the lives and service of the fallen whose names appear on the town’s memorial, in South Street. The talk on which this article is based was inspired by that work.

Even as the war raged it became clear to politicians and others that, given the way that the whole nation was engaged in this total war, new forms of memorial had to be produced, to honour the sacrifice. Statues of generals, portraits of commanders, reflecting the Great Man view of history were simply not enough. This was a people’s war and a generation’s sacrifice.

The War Graves Commission was established by Fabian Ware: it would record and care for the graves of the fallen who would lie abroad, as early on in the war the government decided that it was impractical to repatriate the dead. Ware was assisted by Frederick Kenyon, Director of the British Museum. Three Principal Architects were appointed in March 1918- Edward Lutyens, Herbert Baker and Reginald Blomfield. They would design some of the most iconic national memorials: Lutyens’ Cenotaph remains the focus for the act of remembrance each November, while Blomfield‘s Menin Gate, in Ypres, records the names of those whose bodies were never found.

These memorials were essentially conservative in design, not reflecting the modernist movement in art. This was deliberate. The war memorials would stand for all time as the nation’s testament to its loss and should not therefore be influenced by what might be a passing fashion. A younger generation of artists was less constrained . For example Charles Sargeant Jagger , who had served in the Artist’s Rifles and been awarded the Military Cross, produced one of the greatest of the war’s memorials, that to men of the Royal Artillery. It stands, massively, at Hyde Park Corner. The architect was Lionel Pearson, with Jagger’s bulky bronze artillerymen complementing the huge howitzer. It is in no sense a triumphal memorial. Included among the standing figures is a dead artilleryman.

National memorials were , at the suggestion of Winston Churchill, paid for by the government. The many local crosses and statues around the country were funded by local groups, or families of the dead. Guidance in their design was given by an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum and Royal Academy, in 1919. In and around Dorking we can see the results.

A particularly interesting memorial is to be found in the churchyard of Abinger Common. It was commissioned by Margaret Lewin in memory of her son Charles Mclean Lewin, of the 4th Hussars and records the names of the fallen from both the First and Second World Wars. In form it is a cross, set on a stepped plinth, the body of the cross bearing a “Crusader’s Sword”- because the soldiers were seen as modern crusaders, fighting against evil. It was designed by Lutyens, who had worked on several houses in the area. The architect had originally opposed the idea of the cross as a motif in war memorials, on the basis that it would exclude non Christians. Clearly he reconciled himself to the idea to produce this fine memorial.

It was a painter, Reginald Frampton who was responsible for the wonderful family memorial in St Barnabas Church at Ranmore. Lord Cubitt lost three of his six sons during the war. The family’s experience was, sadly, not uncommon. Traditionally it was from the upper and upper middle classes that the bulk of officers were drawn, although as the war progressed recruitment from the middle and lower classes became necessary. Leading from the front these young man suffered disproportionate casualties in the army. At one point it was estimated that the life expectancy of a subaltern on the Western Front was six weeks.

Frampton produced a highly symbolic painting over the altar in the chapel. An image of the Nativity is accompanied by figures representing the virtues for which the war was, in theory at least, fought- Justice, Hope, Charity etc, with figures representing the national saints of the allied nations in armour. This therefore is the war as Crusade. Such imagery must have been a comfort to families left bereaved: perhaps the deaths of their husbands and sons had not been in vain.

Here, in St Martin’s Church, we see again the employment of Christian iconography in the tablets in the Lady Chapel and nave. They were designed by James Powell and Son who were responsible for the opus sectile elsewhere in the church. Opus sectile is similar to mosaic work except it used larger pieces of stone. For a figure of St George in St Martin’s the firm was paid £80. Both Edward Arthur Chichester, killed at the Somme in 1916 and Henry Harman Young killed in 1915 are depicted as the saint.

These memorials were commissioned by families and in Chichester’s case a memorial tablet, by his brother officers.

In towns and villages up and down the country there are crosses and other memorials erected by the community. Two command our attention.

The cross at Holmwood, some distance from the village and now divorced from the church by the A24, is unusual as its gestation is recorded in a surviving minute book. Written records, showing how memorials were designed or paid for are rare. The minute book, preserved at Surrey History Centre, records how the memorial tablet within the church was designed and paid for and how the committee wrote to the Dorking War Memorial Committee to say they did not want the names of the soldiers from the village included on the town memorial, clearly expressing the sense that the local community felt it had to give local expression to local loss. The initial design by the firm of Earp and Hudson was rejected. This firm had been founded by Thomas Earp, who worked on several Gothic revival churches- was the design at Holmwood too Gothic? There are certainly Gothic touches in the surviving design, around the base.

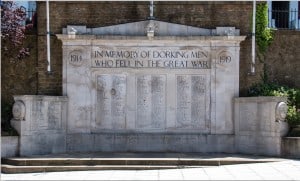

The Dorking memorial betrays no suggestion of Gothic however. Erected in 1921 it was designed by Thomas Braddock. It is classical in inspiration, on a raised platform against a retaining wall and is built of Portland stone. Braddock, later MP for Mitcham, had won a competition for the design and would later add cinemas, including the Odeon Leicester Square, to his portfolio. The memorial, like so many others, was later extended to include the fallen from the Second World War.

Unlike many other memorials the Dorking one does not record rank. Thus, above Harman Young, the Cubitts and Chichester appears, for example the name Edward Clark. Clark was a private soldier and his story must stand, in terms of its poignancy for so many others. He married Lillian Barnes on 30 September 1917. They lived at 12a Watham Road, Dorking. He had enlisted in October 1917 in the Norfolk regiment and a year later, less than a month after his wedding, embarked from Folkestone for Calais and thence to the front. He was killed on 28 October. Photographs of Edward and Lillian and his medals have survived in the family and seeing them bridges the decades since his death and brings home the enormity of the catastrophe that was the Great War.

The war changed many things. It led to the collapse of empires- the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman. The conflict and diplomatic machinations in the Middle East led directly to the problems that beset that part of the world today. At home the wounded , both physically and mentally, were a reminder for decades of the effects of modern industrial warfare. Arguably it also accelerated the extension of the vote-full universal suffrage, including women, coming in 1928. But there was another , less welcome extension of democracy. The Great War was a people’s war. On memorials throughout the country, in the villages around Dorking and perhaps especially in the town’s spare stone memorial, there is another democracy- the democracy of loss.