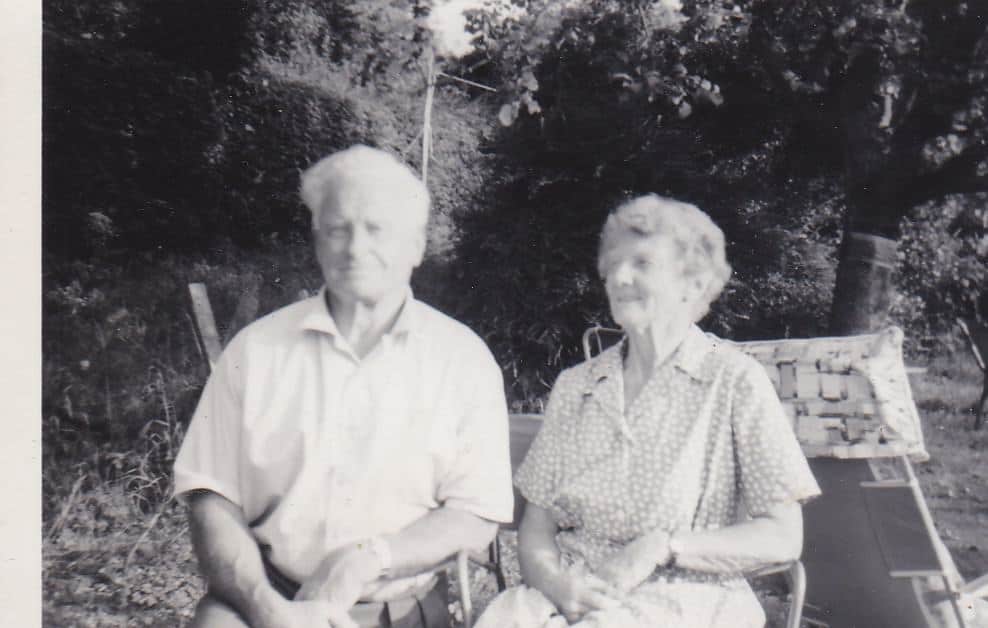

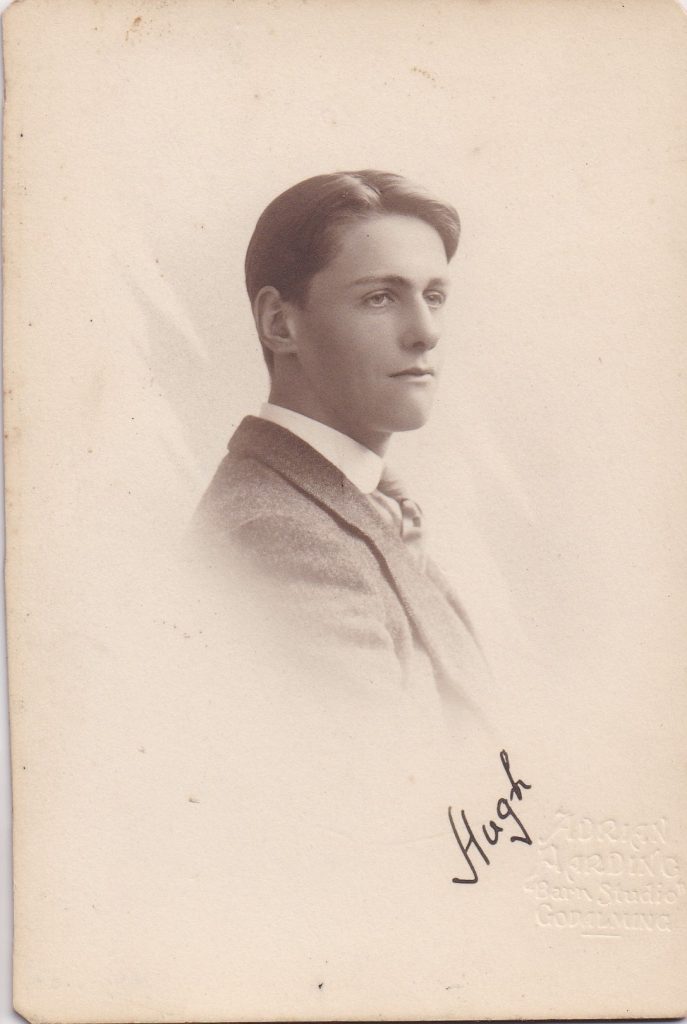

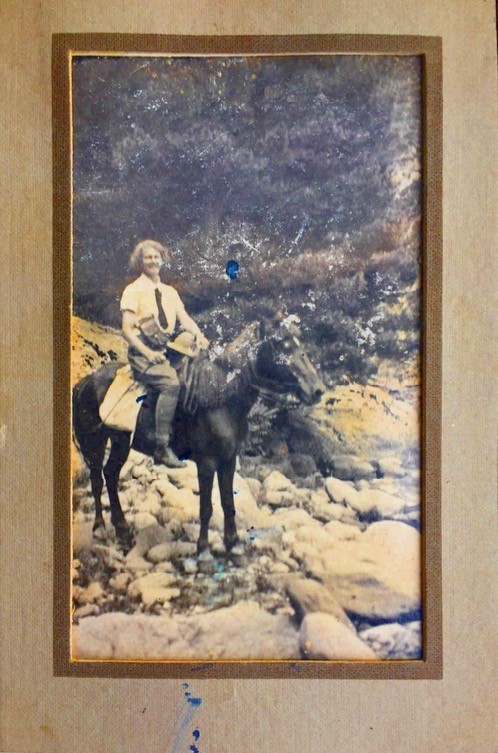

The Museum was contacted by Tania Sweet, who is the niece of Hugh Delafosse Simpson, a Okewoodhill soldier who was killed in France on the 24th August 1917. Tania sent us some family photographs of the family, along with a journey that Hugh’s sister Joan undertook in 1930.

Journey across Iran and Iraq in 1930 by Joan Gillow Simpson (aged 32)

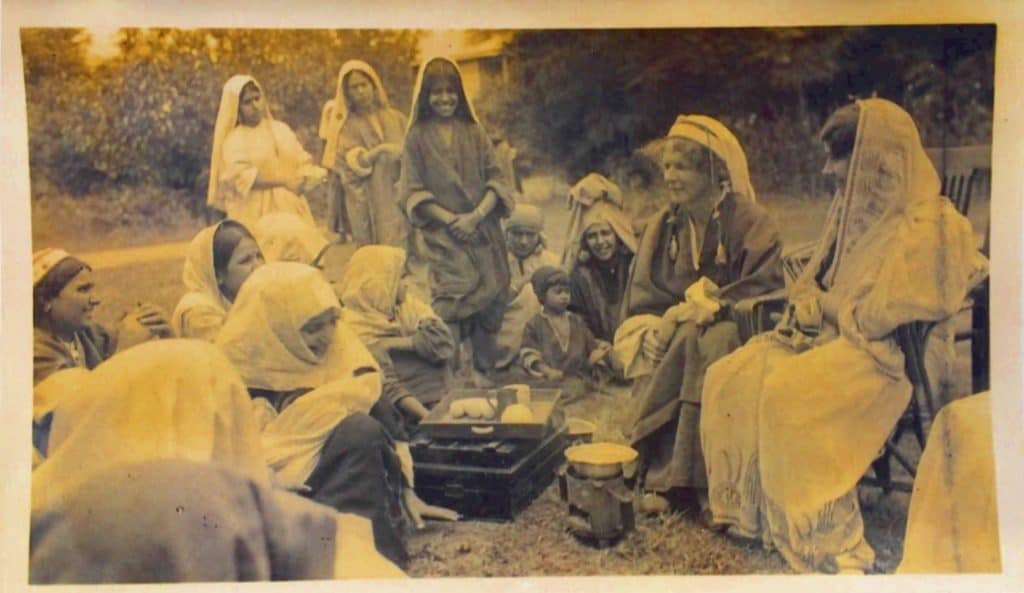

It was a June afternoon in 1930 that we sat at tea on the lawn, under the shade of a weeping-willow in the garden of a mission hospital in Kashmir. I was to go on leave the following autumn, and so was naturally thinking of what route I should take. That through Persia was the one which really attracted me, partly I suppose because there was such a blank in my mind as I looked at its outline on the map. It so happened that of those seated at tea that day no less than two ladies had some experience of travel in this, to me, unknown country. Here was my chance to settle some of the problems of the journey.

“Oh, you can’t go alone,” said one of them, “Impossible, besides the prophet had red hair!” she said looking at mine, and counting me altogether too young and inexperienced to be allowed to stray at large along a route not greatly frequented by English women.

However, the other visitor that afternoon was an Indian lady, who had twice travelled to England by that route and her advice was “Go”. I asked if a woman travelling alone, unescorted by any servant, would be likely to be treated with discourtesy. My friend reassured me on this point, and I felt the lure of the unknown road strongly.

At last the time came, late in October. My nursing duties were over, passport and visas obtained, and “bugs” innumerable, anti-typhoid, anti-plague, etc., had been stuck into my long-suffering body, according to the regulations of the hard-hearted governments of Iran and Iraq. With a minimum of kit I left Quetta for Dugdab on November 10, 1930 by the one and only passenger train of the week, which runs through Baluchistan along the line laid down by the British during the war.

Whilst waiting for the train to start an English woman greeted me, so we joined forces for the 36 hour journey to Dugdab, that isolated little town in the south-east corner of Persia. As my companion was equipped with a Primus stove I was distinctly the gainer, for on that desert journey through Baluchistan you can get nothing but water and water melons, so I should have had to go without a cup of tea had it not been for this lucky meeting.

The country is very arid and rather fascinating, so long as one is safely in the train, for it is unending sand, with rugged mountains on one or both sides of the line.

We arrived at Dugdab the next afternoon and were taken care of by the Belgian customs officer, who refused to let us go to the Grand Hotel, the only one in the place, as he said its roof had fallen in, so drove us to the Mission House, where the kind English missionaries then in charge put us up.

Looking at the map of Persia one would naturally suppose that there must be a fairly direct road from Dugdab to Tehran, but the great desert of Lub stretching across the centre of the country makes this impossible, it was impracticable to take the southern route through Shiraz, Persepolis and Isfahan to see the ancient civilisation of Persia due to the quick sands. Cars have to carry wire netting to put under the wheels and often sink up to the axles, so we made a deal with an excellent fellow, Nazaroff, a White Russian, who was starting with a convoy of four trucks laden with merchandise going to Meshed.

We said farewell to our kind hosts, climbed into the front seat of a vast 10 ton truck, the first of the convoy of 5, each with a Russian driver and cleaner, and drove away through a pass flanked by bare rugged sand stone hills which surround Dugdab.

Unfortunately, Nazaroff spoke only Russian and Persian and as we spoke neither, conversation was extremely limited. At 10pm the convoy halted at a little village in what was evidently open desert land. The whole sky seemed to be filled with stars which swept down to the low horizon. At this stage we were led into a new Shamiana tent, carpeted with beautiful Shirazi rugs. The reigning Shah was touring the country for the first time in 300 years and this tent was waiting for his arrival. We were soon asleep on the floor, and at 3.30am were awakened by Nazaroff who said it was time to start. We roused the man who had allowed us to sleep in the tent and pressed a tomaan (the equivalent of 3/-) into his hand. When he realised what had happened he came running down the road, rubbing his eyes and gave it back to us, and would on no account take anything, so we felt we had indeed been the guests of the Shah for our first night.

We rumbled on at the rate of 12 – 15 mph, stopping at the picturesque village of Shusp for lunch, milkless tea and flat thin bread. There we saw women grinding corn, clad in the pretty butcher-blue home spun which the village men and women mostly wear. The men often have very full blue trousers like a skirt on each leg.

That afternoon we came across another of Nazaroff’s trucks stranded by the roadside with a broken back axle, without any fuss a young pine tree was lashed lengthwise beneath the crippled car, which was then attached to our truck to be towed. The tree, however, broke beneath the weight and another had to be fixed, so we proceeded at 4 mph to the nearest village where we left it. The darkness, the rumble of the trucks and the desert air, together with the fact that we had been driving since 4am (it was now 10 pm) made us sleepy. We both nodded off to be awakened by a swerve, and we noticed that Nazaroff also was overcome by the powers of the night. We decided that we must do our part, so began by singing Scottish songs, when our store of these ran out we continued with “Fight the good Fight” and so forth. As we were both unmusical we seldom hit the same note, but the effect was marvellous and our Russian friend had no further troubles with sleep.

At midnight we reached Birjand and spent the night in a large and very smelly serai. My companion sat up, disliking her surroundings too intensely to sleep, but it did not worry me and soon I was sound asleep on the floor.

Here our ways parted, and next day the 10 Russians and I continued our journey to Meshed. It grew colder as we travelled north and the desert air made one feel tremendously fit. That night we reached Kain, a large village of mud-walled houses mostly one-storey high, each with a roof formed of several mud domes. I was led up an outer stairway to a spotlessly clean upper- chamber. There the butler and valet clad in homespun long blue garments helped me to spread my bedding on the floor. They kindly invited me to partake of food but as I found the ration of time provided for sleep was 3 1⁄2 hours, bade them good night and stood upon the roof for a few moments looking out into the starlit darkness of that vast open space.

3.30am arrived all too soon, but we set off and drove on and on for 5 hours without stopping for breakfast. My lack of the language prevented me from knowing that we were hurrying to a village where we could wait to see the arrival of His Majesty the Shah of Shahs. He came travelling in a closed car followed by 14 others which dashed past where we stood, I cannot say that I actually saw him.

The Shah who is of peasant birth is making his influence felt by his sympathy with the Persian women in their desire for education and emancipation. In the towns they generally wear Parisian clothes and high-heeled shoes, but when they go out it is compulsory by law for them to be veiled. In 1922 there were 612 schools for a population of 12 million. In 7 years the number increased to 3,300, the number of scholars has trebled and the proportion of girls’ compared to boys’ schools has greatly increased.

I met one Persian woman unveiled; she drives her own car and is an excellent mechanic. Her husband, a general, was once attacked by a robber whilst mending a punctured tyre in the desert. It was she who turned the tide of the battle by hitting the assailant over the head with a spare back axle.

On the fourth evening after leaving Dugdab we climbed up the steep mountain road to the sacred city of Meshed, where we arrived at midnight. I remained in the garage that night. In the morning I removed what grime I could with the aid of a bucket of cold water before going to the British consulate. I was much relieved when the servant in scarlet livery provided me with a hot bath before I had to meet my host and hostess at breakfast.

The mosque at Meshed is so sacred that even the shadow of an unbeliever may not fall upon it. The blue minarets and domes are most beautiful.

To enjoy Persian travel to the full one should acquire the Persian temperament, for, though I found them a most charming and courteous people, they seem to agree with Browning’s lines-

“Leave now for dogs and apes, Man has for ever”

They certainly are the world’s worst starters.

I decided to go to Teheran by car, in order to reach there in three days, so the Persian attache at the Consulate kindly engaged a seat for me in a car leaving the following Tuesday. The chauffeur, however, went off the day before without warning. The front seat in a ford was then booked; the back seat had been engaged by two Bolshevik Russians from the Soviet store. The time for our departure arrived but no car! At length we discovered it but neither the lights nor tyres were in working order. I was then advised to go by a motor mail van, my fellow passengers were 2 Persian men and a boy. We wound down the steep hillside in the dark and met long strings of camels travelling between Teheran and Bokhara or Samarkand. It was a complicated matter to get past them and lurid volleys of language called forth from the driver which might have been a liberal education had my Persian risen to it.

The well worn track below the Elburz mountains to Teheran was old in 330BC when Darius fled along it after his defeat at Ecbatana by Alexander the Great. The Persian empire over which Darius had ruled stretched from Egypt to India.

To resume our journey; that night the driver stopped by the road side for a couple of hours, pulled the blanket over him and slept in his seat. I was not so fortunate, it was a bitterly cold night with an icy wind off the Elburz mountains, added to the fact that my feet were cramped between the tiffin basket and the gear levers which made sleep impossible.

In the morning we halted for half an hour at Nishapur, which reminded me of an old Worcestershire market town with its picturesque square. Just outside is the tomb of Omar Kayan, famous to us in the west as a poet though the Persians honour him more as an astronomer and philosopher.

We travelled on all day, stopping two or three times to drink tea, ever ready in the Samovar of a village inn. I was resolved that whenever and wherever it should please my charioteer to halt for a rest, I, at least would lie down. At 1 am on the next morning we pulled up at a serai. Its flaming torch and steaming samovar were a welcome sight, but more precious still was the prospect of sleep. Three hours was the allotted time, so refusing all refreshment, Balla Khana, sleeping room, I said firmly to the driver. He led me through one barn-like room to an inner one which boasted no windows but it had three charpais, that is wooden bedsteads which had planks where mattresses and springs ought to be. That’s yours, that’s mine and that’ the other chaps he said pointing to the three. I minded not who were to occupy the other two as long as one was mine. I rolled myself in a couple of rugs and slept like a log, only once waking to see a tousled black head near by whose owner was still happily far off in the land of nod. At 6.30am mine host called out, “Arise, arise” or the Persian equivalent, I sprang up much refreshed and went out into the darkness of the village street with my thermos and cake of soap to do some light ablutions before dawn.

We all drank tea around a brazier, before starting I remember seating myself upon a pile of Persian rugs as I thought, when Jahan Gir completely hidden under one, turned and groaned.

The Persians were extremely courteous, always making one feel at home

amongst them. The rooms of their inns have a wide seat around the walls.

On this they spread fine Turkoman rugs, you climb up, and sit cross-legged and

drink sweet milkless tea. The men would smoke their pipes, not the hookah,

crack jokes and look for my approval in the most friendly way, reminding me of

the old fashioned cricket teas we used to have on our village green in England.

The pale blue and pink of the dawn spreading over the desert as we drove out between two mountain ranges was very beautiful, a line of 50 camels came padding silently by. We reached Teheran on the fourth day having had only 9 1⁄2 hours sleep en route. Mt Demavend’s snowy peak rises above the road which climbs up and down through the hills and then descends steeply into the broad open plain to enter Persia’s modern capital, Teheran. We went through one of the blue tiled gateways typical of the country. The Arabic inscriptions which ornament them are applied in mosaic and not painted onto the tiles as one might think.

In order to continue my journey from Teheran to Khaniquin on the Iraq frontier I bargained for a seat in a car. Again I had some difficulty in getting them to start. I hoped to get away by 7 am, but it was 2pm before we were really on our way. The car was of American make and well laden with 3 Persian men and a child behind, I was in front with all our luggage strapped about the car wherever room could be found. We drove off across the flat plain to Kasvin at 40mph hoping to accomplish the 235 miles to Hammedan by mid-night; no such good fortune – we had 3 punctures and the jack broke, the cold was intense, but at 3 am we eventually reached Hammedan. I was longing for a bed, but at this point three Persian policemen, with rifles and bayonets climbed onto our already overloaded car and we drove to the police station where they spent an hour searching for opium in the luggage of one of the passengers. At 4 am we entered the courtyard of a large serai which I had to share with a Russian woman. The iron bed had broken springs and a metal bar across the middle. I put my flimsy mattress on it but did not sleep a wink.

I was anxious to get home to England as soon as possible and thought that the next two days could be rolled into one if I shared in driving the car, but the driver laughed at the suggestion and said it was quite impossible. “We cannot start until mid-day as the police are still searching the old man’s luggage. After some difficulty however, I collected the old man, his baggage, the driver and the petrol and we finally started away at 10 am.

Hammedan is built on a beautiful fertile plain just at the foot of the mountains where many roads meet. As I looked at the countryside thoughts of all the massacres and bloodshed which had taken place there came over me. It was known in the 3rd century BC as Ecbatana, where Alexander defeated Darius and later in the 13th century the Mongols swept across Persia from the north east and massacred thousands on this plain as they did also at Nishapur.

Next day we crossed several mountain ranges along a magnificent road made by the British troops during the war. We passed most picturesque and ruffian looking Kurds with their flocks and tents of homespun goats hair cloth. At dusk we arrived at the frontier between Persia and Iraq. We had passed so many customs posts during the day that I did not realise that the barbed wire meant the frontier half a mile from Khaniquin where I was to take the train to Baghdad. Our luggage was strewn on the ground, and a rather tiresome customs official brought my mind back with a jerk from the beauty of the sunset to the realities of the moment by saying, “You will have to stay here all night”. I was quite determined that I would not do so. I asked which of my suitcases they wanted me to open, the official replied, ”I don’t want your luggage opened, it’s your money I want to see”. Thinking they were not entitled to ask for this, I refused. He questioned me as to how much Persian and how much Indian money I had, and at length said that I must be searched. I replied that I was quite willing and went with an old woman behind the rickety door of a courtyard where she patted me up and down and felt in my pockets and found nothing but my Thomas Cook’s travellers cheques.

Eventually I discovered that we had reached the frontier so I willingly handed over my Persian money in payment to the driver. This satisfied the customs official so all was well. Persia was on the verge of bankruptcy so the rules forbidding the import or export of Indian rupees or export of Persian silver were very stringent, though not understanding the language I thought the customs officer was trying to rob me.

Next morning I reached Baghdad by train. It is full of interesting sights, both ancient and modern. The bazaars are full of lovely eastern silks and rugs and in old Baghdad there is the beautiful Mosque with its golden minarettes and domes where the Calif Haroun Al Raschid of Arabian Nights fame worshipped.

I took a car and drove out to Babylon over the roughest road I have ever endured. I was the only passenger in this ancient car and the Arab driver crashed on at top speed over this very bumpy desert track, what with catching my camera, replacing the seat, hitting my head against the top and regaining my perch I was thoroughly occupied all the time. As you travel over the desert you see ridges in the sand about 3 ft high which are the remains of the irrigation scheme made by Nebuchadnezzar in 605 BC. He also built the Median Wall, a great dam which stretched from the Tigris to the Euphrates and enabled him to flood all the country north of Babylon.

At last, much battered, I arrived at the first great mound, the ruins of Ancient Babylon. It was an awe inspiring sight to stand before this mighty pile of sand and brick rubble at the entrance of this city which had such a marvellous civilisation and its history so closely connected with the bible.

The landscape is now simply sand, broken by great mounds at some distance from each other. Babylon the Great was a walled city standing four square, through which the river Euphrates ran. Between the inner and outer walls there was room to grow a year’s supply of corn, thus enabling the inhabitants to withstand any siege. Now the green line of date palms runs outside the ruins showing that the river has changed its course.

I went on to the next of the excavated mounds and offered one of the Arabs baksheesh on condition that he would keep the others away. I was left in comparative peace to try and visualise the past. Here I saw the walls of the temple of Marduk, built of brick with a frieze of unicorns on the bricks. There are many rooms, some of which had been part of Belshazzar’s Palace. The centre portion I was assured were the ruins of the famous Hanging Gardens.

The glory of the past still seems to cling to these old walls, reminding one of the high code of Law and Justice on which its civilisation was founded, drawn up by its ruler Hammurabi, who died in 2213 BC.

By the waters of Babylon I sat down to a meal of dates freshly gathered from the palms.

It is a 12 hour journey from Baghdad to Ur of the Chaldees by rail. This was one of the most ancient of the numerous city states of the old world, going back to the 14th century before Christ. Two miles from the railway rest house across the sands is the ruin of the great Ziggurat Tower, akin to the Tower of Babel. From the top there is a good view. Below to the east are the remains of Abraham’s city, beyond are the royal tombs, in front the temple of the sun and Moon god and goddess, and all around as far as the eye can see is sand and nothing but sand.

If we go back in imagination to 400 BC, Ur was the Venice of the Kingdom of Sumer. The vast river the Shatt-el-Arab flowed past it and shipping made fast to its harbour walls. Ur was the centre of trade and commerce. The land was flat and green and the waves of the Persian gulf, now nearly 120 miles away, lapped close to its walls.

We owe the earliest known form of writing to its civilisation, the cuneiform script, the beginning of the sciences of medicine and astronomy, also the forerunner of our clocks and watches.