The current plotline of Radio 4’s The Archers has the cast enacting an Easter pageant. The plot of the Ambridge Pageant sees the countryside under threat from characters who will exploit and destroy it. It celebrates the heritage of the land, and the landowners and farmers who have worked in harmony for centuries. It is a political piece, addressing local (and national) concerns about the destruction of the countryside. But it is not a new piece. It was written in 1938 by the prestigious pairing of the novelist EM Forster and the composer Ralph Vaughan Williams. And it was originally performed at Milton Court near Westcott to address concerns about the threat to the countryside in the Dorking area.

Forster was not a natural ‘villager’; he was unsympathetic to the class distinctions of village life and at odds with the local gentry, who, he felt, had too much power. But he made many friends nearby, amongst them Max Beerbohm in Abinger, birth control pioneer Marie Stopes at Norbury Park, and Labour MP Fred Pethick-Lawrence and his campaigning wife, Emmeline, in Peaslake. It was in response to threats to his community that Forster came to write his two ‘pageants’. The first was written to raise funds for the church restoration fund in Abinger. Vaughan Williams provided the music.

Vaughan Williams, who lived at White Gates off Westcott Road, had egalitarian ideals and with the hugely popular Leith Hill Musical Competitions he had fostered musical participation of the highest quality for the whole community, rich and poor. ‘The composer must not shut himself up and think about art,’ he said, ‘he must live with his fellows and make his art an expression of the whole community.’

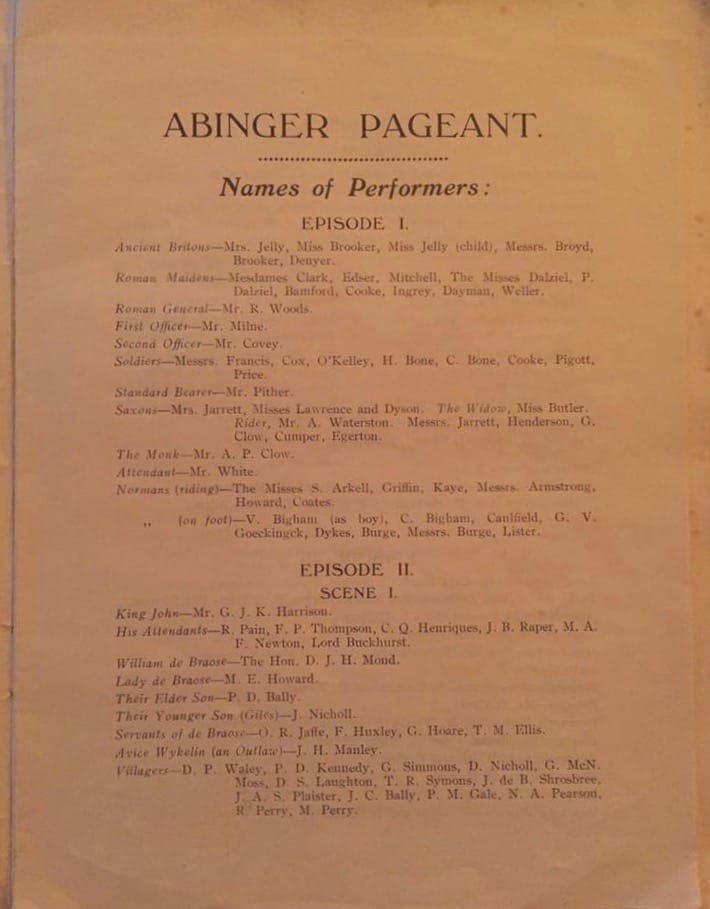

In calling their work a ‘pageant’, Forster was harking back to a more ancient dramatic form, combining music, drama and spectacle with a large cast. The Abinger Pageant set the church at the centre of a community with long traditions. Presented at Abinger Rectory in July 1934, and produced by Tom Harrison, it had 500 participants including a band and a choir. The narrator, a woodman, presented the history of Abinger from the time of the ancient Britons, and threats to its inhabitants from Romans, Saxons, medieval kings, Spanish Armada, Civil War, smugglers and excise men to the modern threats of by-passes, petrol pumps, pylons and arterial roads. The pageant pays homage to John Evelyn of Wotton for replanting trees lost to ironworking in the seventeenth century and calls for the preservation of the countryside: ‘if you want to ruin our Surrey fields and woodlands it is easy to do, very easy,’ says the narrator, ‘and if you want to save them they can be saved.’

Forster returned to the theme of preservation of the countryside again four years later, when he wrote the pageant on which The Archers’ current offering is based. England’s Pleasant Land was presented by the Dorking and Leith Hill Preservation Society (Vaughan Williams was chairman of its committee) at Milton Court, Westcott on 9th, 14th and 16th July 1938. The Society (established in 1929) had been founded in response to threats to the countryside in the wake of the break-up of large estates that saw building on many beauty spots all over England in the years between the wars. The composer called upon eminent musical friends to provide pieces of music and William Cole provided a fanfare. Vaughan Williams himself conducted the choir and band of 2nd Battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Regiment, whilst the 5th Battalion of the Queen’s Royal Regiment played the part of the local yeomanry. England’s Pleasant Land takes a more in-depth look at the threats to the countryside over the ages, and the struggles of those living there to preserve it. Concentrating on the impact of the enclosure of common land in the 18th century in the first act, and that of the introduction of death duties in the second, it compares the threats of the 1930s with those of the past; Linda Snell is drawing the same parallels with today’s threats in The Archers, (type) casting Justin Elliot as the wicked developer.

A prologue sets up the establishment of the ‘old order’ in the countryside after the Norman Conquest, with squire and villager living in harmony on the land. In the first act, set in 1760, good Squire George (of course!) is persuaded by modernizing Squire Jeremiah to enclose his common land, which robs the peasantry of their commoners’ rights, leading to poverty, revolt and violence, with villagers attacking the manor house and soldiers putting down the insurrection. The second act opens in a peaceful 1899 where Squire George’s descendent and the villagers celebrate a Domesday party and the children of the squire and the children of the village look towards a future together in friendship . But on the death of the old squire, his son is faced with the newly-introduced death duties which he cannot pay without selling the land which is his heritage and that of the villagers. Death duties bring land onto the market, and Squire Jeremiah, now in the guise of Jerry the builder, moves in. ‘Ripe for Development is England’s Pleasant Land’, he chants. There follows a pageant of horrors – cars, buses and bikes, paper litter and empty tins, and pedestrians being run down.

The pageant presents a somewhat romantic view of the ‘natural’ order of things, with the old gentry protecting the land and the builders and developers preying on it for profit. It ends with the choirs singing Blake’s ‘Jerusalem” and ‘I vow to thee my country’, and the epilogue calls for a new order to replace the old if England’s green and pleasant land is to be saved.

The novelist and composer collaborated again on the foundation of the Dorking and District Refugee Committee in 1938. Tackling another issue with relevance today, they sought to help those fleeing Nazi Germany into homes, schools and employment in the Dorking area. When trying to sum up what was worth fighting for in the face of invasion during the Second World War, Forster wrote about Abinger and the lives of his neighbours, naming his collection of essays Abinger Harvest.

Forster’s connection with Dorking and Abinger came to an unfortunate end in 1946. The lease on West Hackhurst expired and he was forced to leave. The villagers, who had initially found him aloof, if not distinctly odd, saw him off with a rousing party at which he gave a speech in defence of local footpaths. He spent the rest of his life in London and at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Vaughan Williams went on to carry some of the ideas tried out in England’s Pleasant Land into his fifth symphony. He became president of the Dorking and Letih Hill Preservation Society in 1950; the Society (now known as the Dorking and District Preservation Society) remains active in working to preserve the environment in Dorking and the surrounding villages.

The issues that the composer and novelist addressed in their pageants remain as relevant today as in the 1930s; during the Green Belt Consultation a year or so ago community groups formed all over the area to present the views of local people and to fight designation of areas of community value for development. The debate as to what and how much development is appropriate in the countryside is a never-ending one; but It is fascinating to see the creative community activism of the pageant contributing to the national debate, nearly 80 years after it was written.