Quests for Immortality

1527 – “Paracelsus Laudanum” written by Paracelsus introduced opium as a medicine to the West at the ripe time it was emerging from the dark ages. Following his travels in Arabia he returned with a famous sword within the pommel of which he kept “Stones of Immortality” compounded from opium.

(An aside -In Greek Mythology: Ambrosia was considered the Nectar of the Gods – a sacred food made of honey and other secret ingredients to ensure immortality).

Paracelsus is credited with developing the standardised “tincture of opium” – a solution of opium in ethanol. It was known as laudanum. Compounded from opium, thebaicum, citrus juice and the “quintessence of gold”. It has become the basis of many popular patented medicines of the 19th C.

He viewed himself as greater than his precursor Aurus Cornelius Celsus and his pseudonym Paracelsus is a play on this. He also burned in a public bonfire the Canon of Medicine, the de facto medical text book since 1175, and other seminal works of those who came before him.

He was often obscure but he had moments of lucidity, even of illumination. In one of those he compared the action of his laudanum to the rekindling of the candles of faith and hope in the soul which the ill winds of doubt and despair had extinguished.

Patent Popularity & Cordial Thinking

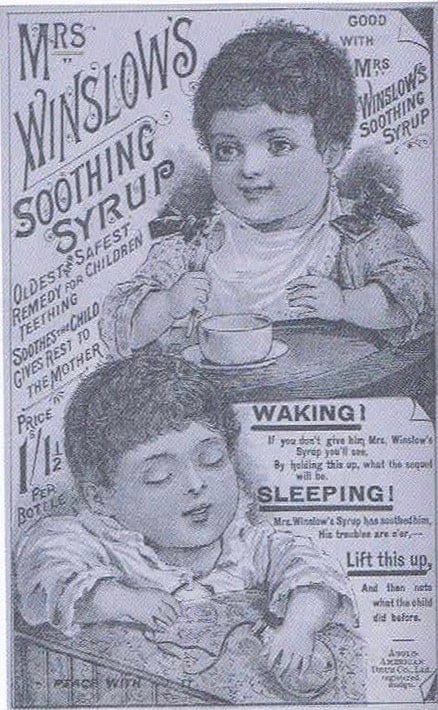

In the 1840’s the first popular patent opium medicines made their appearance: Stott’s Unique Fruit Cordial (for children), Sydenham’s laudanum (based on the tincture by Paracelsus), Dover’s powder and Chlorodyne.

“Chlory did not stave off hunger but it reduced the cry to a whimper”

Alchemical Dreams of Gold & The Shape of Dreams

Early 1800’s, organic chemisty led to the discovery of the alkaloids of opium.

The concept of an ‘active principle’ in opium was ancient but for many centuries was regarded as a pipe dream. There could be twenty ‘essences’ in poppy juice, some with opium-like action but many without. An apprentice pharmacist, named Seturner, had hit gold. He had isolated a compound and named it Morphine, a name derived from the Greek work ‘morphe’ – short of ‘the shape of dreams’. (Not named after Morpheus, the Greek God of sleep).

In 1841, a surgeon in Lyon, Pravaz invented a hypodermic syringe with a sharp, pointed hollow needle. Dr Pravaz carried his precious object – a silver syringe with a platinum needle – not in his medical bag but in a specially constructed pocket in the silk lining of his top hat.

Many of the Victorian elite became expert at wielding the pravaz. Small ‘ladies’ models, some with delicately engraved silver plungers, were advertised in the press. A ‘unique’ set in gold in a finely worked ivory étui could be purchased as a ‘cadeau d’amour’ from a famous Bond Street jeweller still in business today.

Towards the end of the 1800’s many physicians were beginning to regard the syringe and a box of phials as professional adjuncts, like the stethoscope or thermometer. It was not unusal to depart on daily rounds with a syringe and a full bottle of morphine in their frock-coat pocket and return home with the bottle empty.

Recently formed medical bodies at this time, the British Medical Council (a trade union), and the General Medical Council (a self-regulating authority) lent weight and moral credibility to administer morphine. Pharmacists were also vying for power in that qualified chemists were a learned profession and uniquely placed to administer to patients. Both professions agreed it should be taken out of the hands of grocers, tobacconists, wine merchants and pet-food suppliers.

Honeymoon periods

From the perfume-bottle glamour of laudanum to the chilling technique of the syringe lacking in romance…

Administered at the bidding and with the blessing of doctors; towards the end of the 19th century there was an epidemic of people addicted to morphine. Whilst opium’s addictive qualities were known about for thousands of years; through the lens of the medical profession, addiction was looked upon as a disease.

1874 – St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington

Dr Wright, a chemist and future Fellow of the Royal Society, tried to find a derivative of morphine which might be effective but not habit-forming. His experiment resulted in diacetylmorphine (diamorphine). He fed the greyish powder to his dog who became violently ill, so he binned the experiment.

20 years later – A young professor of chemistry, Dreser, from Göttingen University, and in part-time employment for a struggling pharmaceutical firm, Bayer, was scouring old journals. He repeated Wright’s experiment.

No ethical committees existed at that time. His test subjects described its effects as ‘wunderlich’ (miraculous), even ‘heroisch’ (heroic). This inspired him to name it heroin.

Hope, that most precious of commodities, was kindled. Bayer felt it unethical to withhold such an elixir from the public. The launched it under the name of aspirin; heroin would make the firm’s future. It was also discovered that heroin satiated withdrawal from morphine. However, the honeymoon period for heroin did not last as long as it had for morphine. The withdrawal from it was horrendous as a measure of its addictive power.

Present day: There is a known opioid crisis in the UK and USA. Purdue Pharma which makes the drug Oxycontin filed for bankrupty on 15 Sept 2019 due to the lawsuits against it as being largely responsible for this epidemic. It is owned by the Sackler family, sponsors of art museum wings and collections the world over. Over the past year there have been many protests at galleries to ethically question the root of donations received.

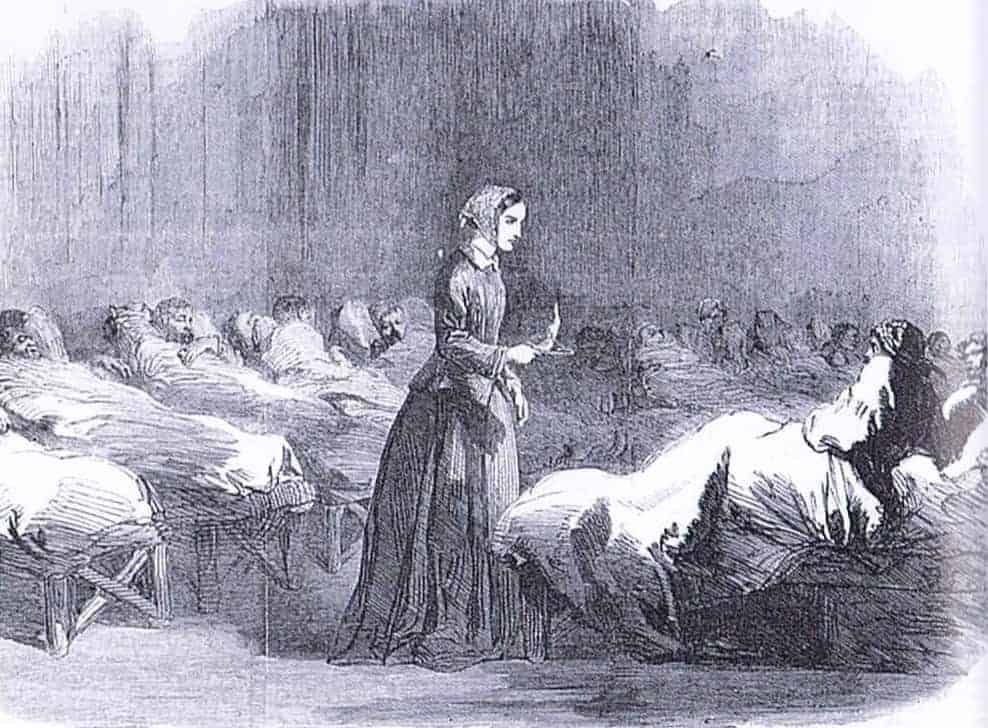

The ‘Lady with the Lamp’, the famous illustration in the Illustrated London News showing Florence Nightingale on a night round in the military hospital in Scutari during the Crimean War. The patients, mostly wounded from the battlefield, must have been heavily dosed with opium to present such a peaceful picture, and so, by her own account, was Nightingale herself.

Opium – Reality’s Dark Dream – by Thomas Dormandy

Thomas Dormandy was a refugee following World War 2 from Hungary. He lived in London. He is best known for revealing the role of “free radicals” in the 1960’s – highly chemically reactive atoms and molecules which are thought to contribute to diseases such as cancer, stroke, heart disease, diabetes and alcohol induced liver damage.

“Opium – Reality’s Dark Dream” was the last book he wrote, a year before he passed away in 2013. His book takes on a rich journey of the poppy. He recognises how it has inspired for thousands of years, has led to medical advances as a result of shared knowledge across lands and languages, and how opium trade routes have led routes to war. He presents the dark reality that in Britain’s desire to be heir in the world to the Roman Empire, a blueprint for Victorian empire building was drawn up against the backdrop of opium trade and principles of free trade. In 1840, 1/6 of public revenue of Britain was derived from tea tax and profits from opium – there was cause to go to war with China – furthermore revenue was needed for reforms in India and the poppy was a form of currency. There was uneasy disagreement in the House, some said “we are about to be engaged in a war… (for no) cause other than the pursuit of profit”. The Opium Wars, in the end, ceded the port of Hong Kong to Britain.

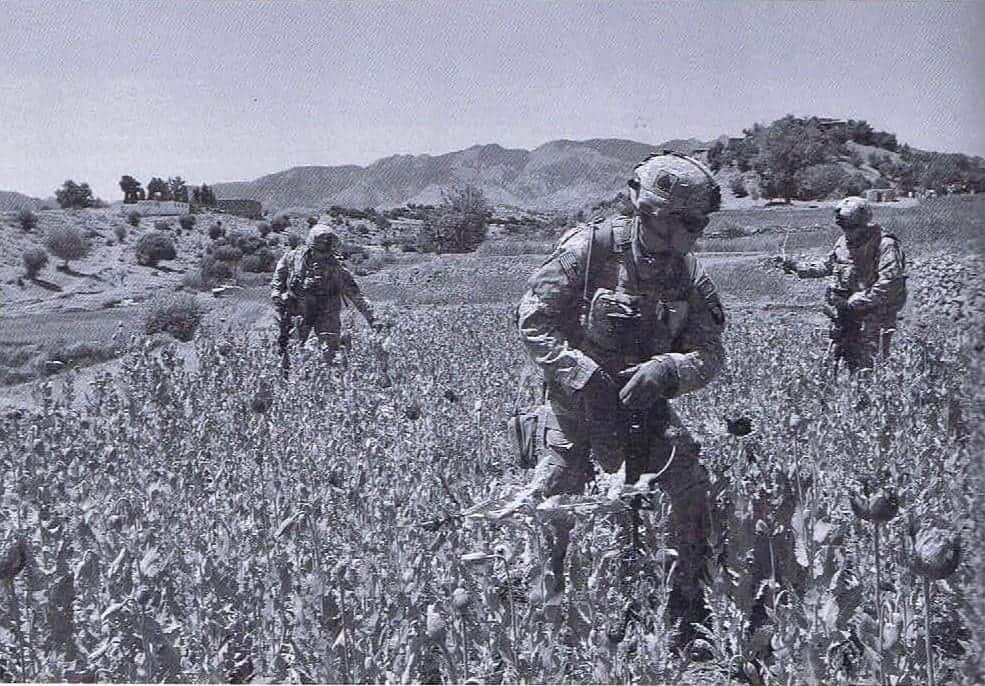

Dormandy takes the reader on a journey to the present with anecdote, biomedical and historical fact. Through this reading we have glimpses into the world of Florence Nightingale during the Crimea War. He mentions the International Red Cross’ original function was the provision of painkillers, especially morphine, on the battlefield. We understand that the first mobile-blood transfusion on the frontline would not have been possible without morphine during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. He journeys us to Afghanistan where the Taliban decimated opium production in 2000 and how its production rose with the fall of the Taliban in 2001. With drought in Afghanistan in 2008 and 2010 there was a shortage of diamorphine in the UK to treat patients. At this time lilac poppy fields, the opium poppy, dotted the landscapes in Hampshire, Hertfordshire and Lincolnshire. The locations of the fields were kept secret. The 2008 crop would have been made into more than 100 tons of morphine and codeine for use in the NHS.

We understand that palliative care exists because of opium. We understand that opium has made possible life-giving and life-saving operations. We understand the reality of our dependency on the poppy is not without complexity as we weigh up notions of empathy, calamity and responsibility.

“Open Hearts” ….

Message in a bottle from friends in South Africa to Dorking

If only they could see

We come with open hearts

Seeking safety and peace

Our hands are not open

We do not take or beg

Our hands are full

Clutching precious gifts

To build a place called Home

If … they could see

We come with open eyes

Seeking our shared horizon

All that is wet

is not tears or sweat

We are full

Its water we carry

To nourish a place called Hope

…Then they would welcome us

and open one more border

into the heart

to plant a seed for tomorrow

– R. Minyuku and daughter (11 years old)

Last : The Symbol of the Poppy

Next : Opiates on the High Street