Arrival in Dorking

In September 1940 we moved from Chipping Norton to Chichester Road [now Chichester Close] in Dorking.

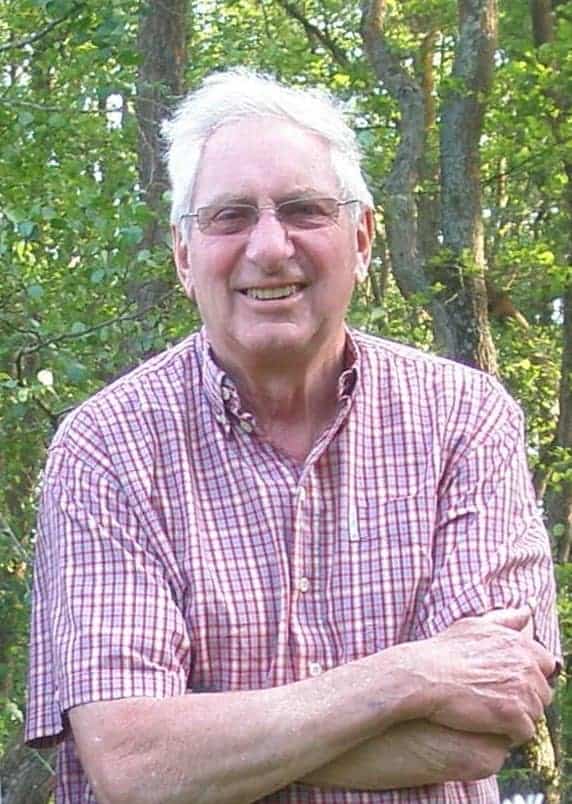

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

The house, Bradley Mead, was I believe built in the 1930s, originally for some Americans and was the only one in the cul-de-sac to have central heating! Insulation had not been a priority and there was a coal shortage due to the War, so the house was uncomfortably cold and, in the winter, frozen pipes were not uncommon. Even after the War was over and fuel for the boiler was freely available, the windows used to ice up in the winter. There was a slightly subterranean air raid shelter of brick with a concrete slab roof built into the rockery at the front of the house. Since the Battle of Britain started days before we moved in, I believe we slept for a short time in this cold and damp room. I think my first memory of Dorking was that of seeing clouds of German bombers going overhead during the Battle of Britain.

I think my first memory of Dorking was that of seeing clouds of German bombers going overhead at the beginning of the Battle of Britain. I could very soon recognise the difference in engine sound between British and German planes. All very exciting!

At that age I don’t think I realised that we were so close to being invaded by the Germans or indeed of the devastating effect that the invasion would have had on our family – particularly since I now believe that my father was involved in some kind of resistance group.

To me, life must have seemed fairly normal in contrast to the lockdown problems due to the Covid virus which children face today. We went to school normally and we were not in a target area for the air raids – we only suffered the occasional stray bomb. We could still visit shops although generally stock was limited. I could keep pets and we had chicken.

My father was not eligible for early call-up because of his age, his profession and presumably any covert activities in which he was engaged. However I was aware of other fathers not being around. I’m sure this would normally have been played down by the mothers of my friends. Wearing a gas mask appeared to be rather a game. It must have been quite different for the evacuees separated from their parents and for children still living in heavily bombed areas.

Air Raid Shelter at Bradley Mead. Photo courtesy of Herbie Battye

Inside Air Raid Shelter at Bradley Mead. Photo courtesy of Herbie Battye

Exit towards Bradley Mead. Photo courtesy of Herbie Battye

Ours was a house without any alcohol – probably because my father came from a Strict Baptist family. It must have been about 1944 that father suddenly announced that he was going to put a beer barrel in the air raid shelter and he started going down the shelter to draw beer! Subsequently about 1946 it became my workshop but being fairly dank I moved my workbench etc. to a new shed at the bottom of the garden. The picture shows the house after 1946, when the area on the right-hand side had been filled in and turned into a sun lounge. The construction work was done by Arthur & Son, local builders. In the house were several oak beams primarily as decorative features, which are supposed to have salvaged from wrecked ships. It was not long before I slept in an area in a recess by the fireplace in the dining room ‘protected’ by an oak beam. Our house, Bradley Mead, was the second house up on the right-hand side of the cul-de-sac. The corner house was occupied by the Mills family. Paul was my age and Peter Mills was somewhat older. Peter became surveyor for the Church Commissioners and a highly respected local councillor.

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

The second house was occupied by the Watkins family. The father was I think editor of the Catholic Times and there were about three children, all somewhat older than I. On the other side of us were an old couple. Then the next house had a family called Gill, with a girl Judy of my age and a boy, David who was slightly older. The father Bertie Gill [very formal in those days – always Mr Gill to me!] Mr Gill asked me if I had any ideas for clamping clips for assembly of beer crates and this was the subject of my first invention. When the Gills moved, the house was bought by Sir Edward and Lady Joan Raeburn. I kept in touch with Joan until she died about ten years ago in 2010.

There was a private school called Stanway further up the hill, with its entrance also onto Chichester Road. The end of our garden abutted onto Stanway’s garden. For the first year in Dorking I went to this school. I moved to Belmont School, then, in Westcott, about 3 miles away after the first year.

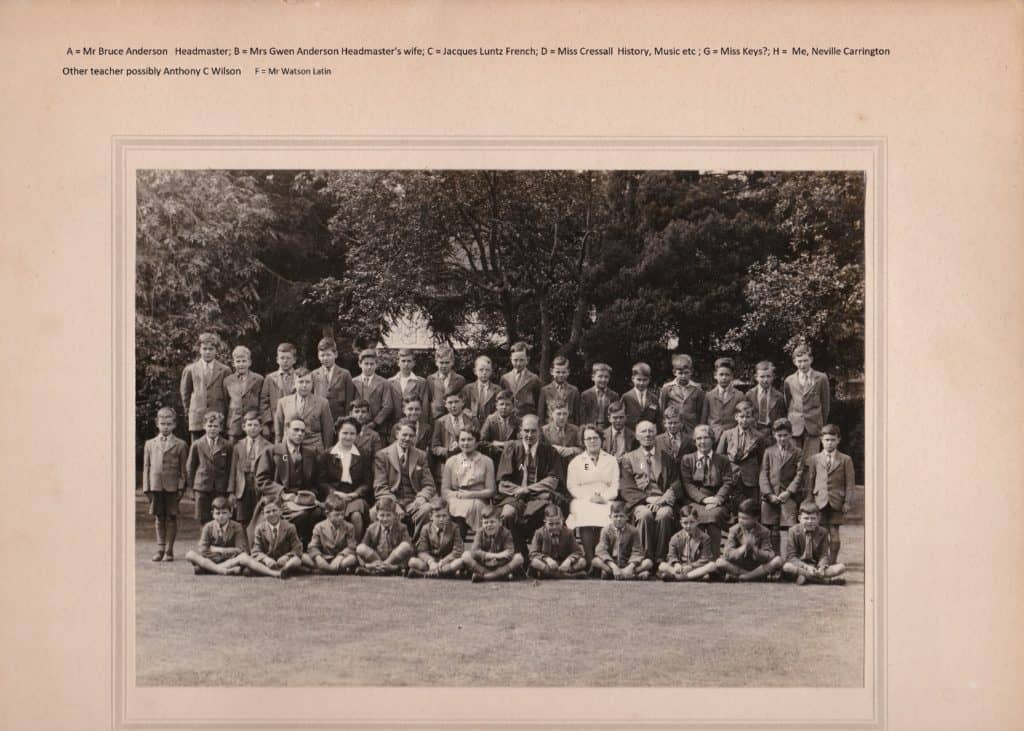

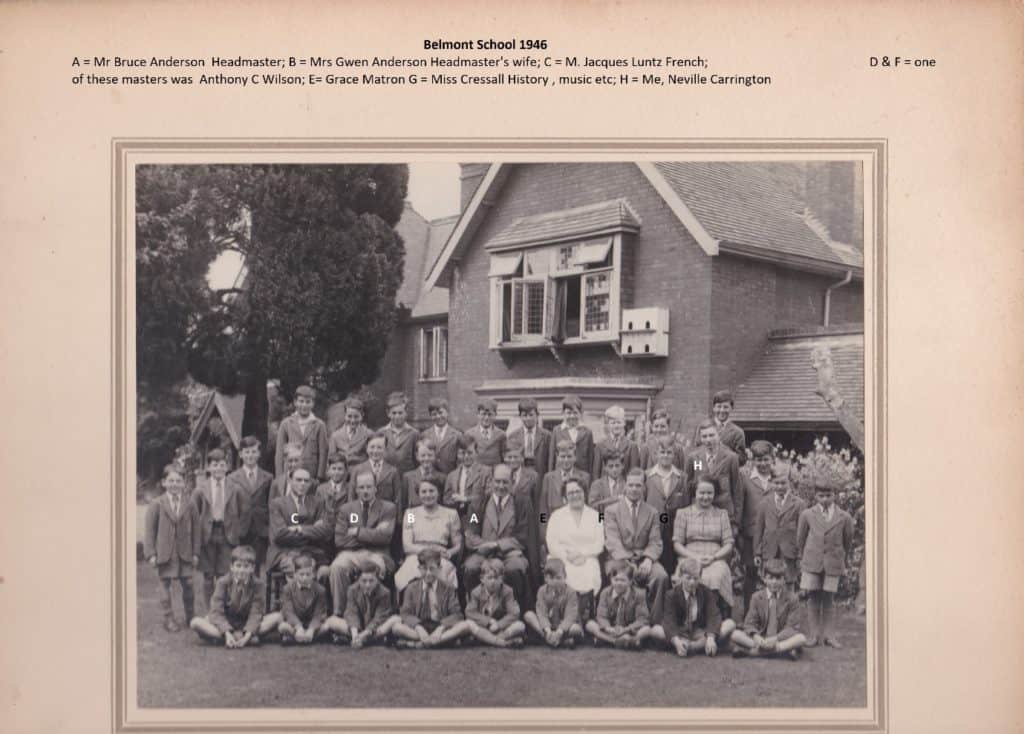

School days at Belmont School 1941 – 1946

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

Bruce Anderson was the headmaster of Belmont. A kindly rather fatherly man. His wife, Gwen Anderson I don’t believe taught but was very much involved in the welfare of the boys. The school started with assembly in what I recall could have been a converted barn where Mr Anderson conducted prayers and I think we had a hymn. Mr Anderson used to cut the playing field with a large motor mower.

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

The French teacher, M. Luntz, I think was from Russia. He lived with some relations in the more expensive part of Dorking. He always smelt strongly of some kind of fragrance and he was always well dressed with spats over his shoes. However he was regarded as a target for amusement and had great difficulty in maintaining class discipline. One of his favourite expressions was “Give me your treek!” One year when I failed to get any other prizes, M. Luntz arranged for me to get a French prize – probably because I paid attention more than some of the others. I think his teaching was the foundation for my eventually being reasonably competent in French for business.

The younger man in the picture below was I think Anthony C Wilson who may have been in the Spanish Civil War, and he probably taught English. He also wrote plays for radio.

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

By 1946, when I left, the number of pupils appears to have dropped from about 46 at the beginning of the war to about 35.

I was a somewhat sickly child and I spent quite some time away from school. I think it may have been some kind of gastric problem. I was prescribed extra milk and I think excused from sport.

I travelled to Belmont on the bus, which stopped on the main road a short walk from our house. At the age of 8; I imagine my mother must have taken me at first. I don’t remember just when I started travelling on my own but attitudes to the care of young children were more relaxed then.

Before the D-Day invasion in 1944, there were many Canadian soldiers camping in the area. So it must have been in 1943 at the age of 10, along with all the other boys, we must have continually pestered the soldiers for Sweet Caporal cigarette cards “Please do you have any Sweet Caporals?”. This was presumably a goodwill exercise for the Canadian army but we felt perfectly safe wandering about and talking to the soldiers. [Read Bill Lancaster’s memories of the Canadian soldiers here]

When the Germans started to send over flying bombs [‘Doodlebugs’] we got used to hearing the characteristic throbbing sound of the engines, and when the sound stopped it meant the bomb was descending – a frightening experience. I remember diving under the dining table at school lunch. Finding food for school meals must have been a problem then – I’m fairly sure that we used to eat horsemeat. One doodlebug or maybe a V2 rocket actually demolished a house in Westcott killing a family which had come down from London for a quiet weekend.

On another occasion I saw a doodlebug come down the other side of the valley to Chichester Road and when it exploded, I saw the dark compression rings go over us and shatter windows in Stanway School on the hill.

When D-Day came along, the sky over us was crowded with gliders being towed across to land in France. Whilst maybe not quite understanding the significance there was certainly a sense of excitement.

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

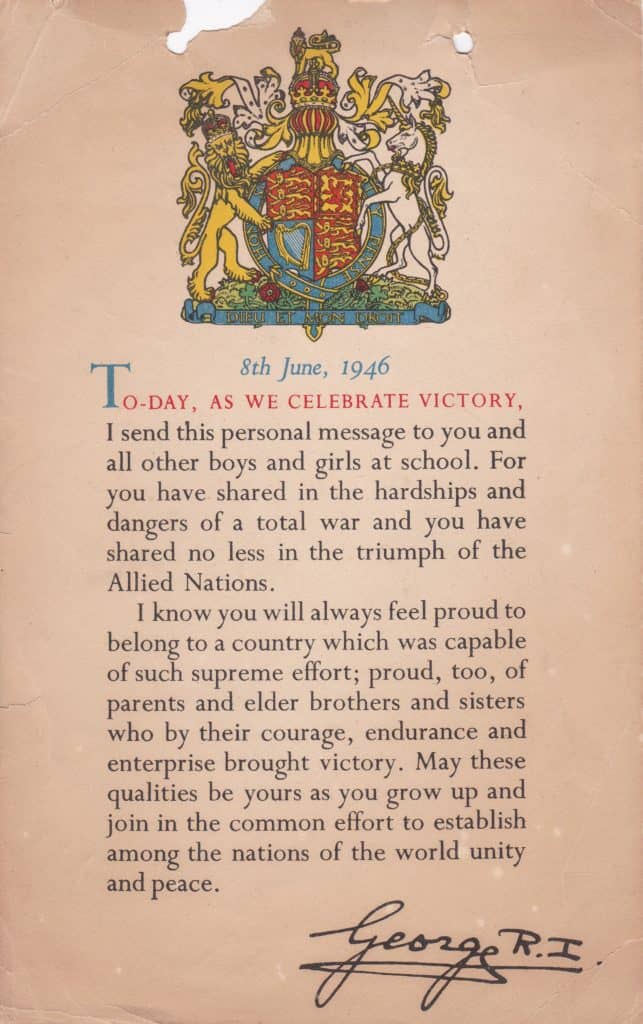

The day the war officially ended in 1945 – VE Day I remember we still had to go to school – feeling somewhat cheated! After the defeat of the Japanese I had a letter from the King commemorating the final end of that conflict.

We had a carpenter, who taught us to make mortice and tenon joints among other things. Because of my interest in model engineering and metalwork, my father bought me a lathe about 1945 from someone in Westcott, which had been owned by a Michael Clinton. I believe the previous owner had been killed in the war and the lathe was sold to us by his father. I remember the woodwork teacher, Mr. Ashbee, who made the War Memorial in Westcott Holy Trinity Church saying slightly disapprovingly that I had a lathe, implying that I was spoilt – which I was! I soon started to make steam engines and tried to make jet engines, as in the doodlebugs.

I had a friend Kit Laurenson living also in Chichester Road and we heard there was a tank on the hillside at Denbies. We went on a foraging expedition to see if there was anything I could use in my model making, and I brought home some bits of equipment and cut off some lengths of copper pipe, some of which I still have! I believe three tanks were buried on the hillside and have recently been excavated. I mentioned this to Sir Adrian White from Denbies, when I last saw him and he told me the tanks had been exhumed and were all being restored.

Although I didn’t take school very seriously, I was extremely good at mathematical puzzles. When it came time to move on in 1946 I was entered for a St John’s scholarship. I didn’t get one and my Common Entrance results were very variable reflecting my interests. I think I did quite well in maths and I took the chemistry exam without any formal teaching – just from my father and his enthusiasm for the subject. I achieved in the 70%s for Chemistry but unfortunately only 6% [how could I forget?] in History. Sorry Miss Cressall!

After my 17th birthday, I learned to drive on Father’s 1939 Rover 12. This was a well-built car with a synchro gearbox [not needing to get the gears exactly matching when changing gear with a simple clutch movement]. I had no formal lessons but managed to pass my test at first attempt after about 3 month’s practice. I don’t think I drove particularly well but I must have had a tolerant examiner. What I think impressed her was that I knew the theoretical stopping distances! I was studying physics at the time and I knew that kinetic energy was ½ the square of the speed for any given mass. So at 20mph the braking distance was 202 /20 = 20ft. and at 40mph, 402/20 = 80ft. Add to this the numerical speed as thinking distance, you get 40ft. at 20mph and 120ft. at 40mph! I just worked it out in my head whilst she thought I had learnt it!

Photograph courtesy of Neville Carrington

I was spoilt by being given a 1931 Austin 7. This car had been used as a tractor during the War and needed a new hood. I learnt a lot about motor mechanics from this car. Although very basic and over 20 years old, the car was very reliable although the cable braking system left something to be desired! This old car, FS1192, is the only one of my former cars still registered in 2020.