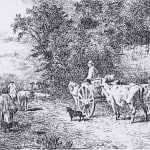

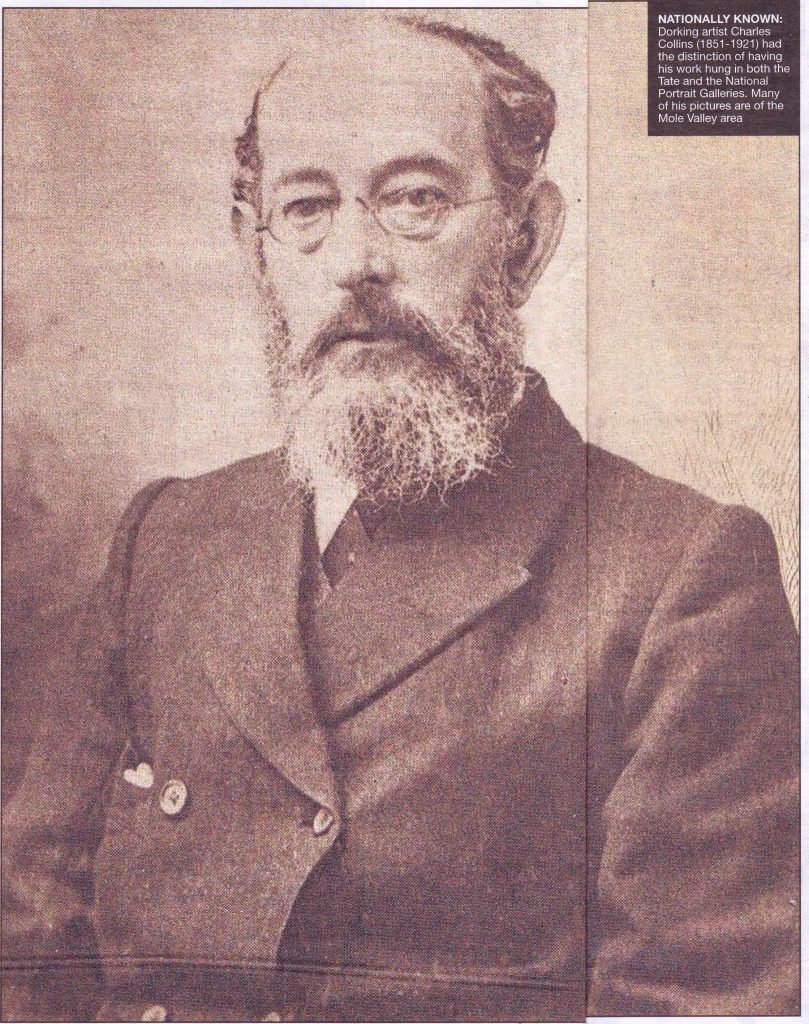

Charles Collins, as he was known, was born in Hampstead in 1851. He began painting pictures at a very early age starting with landscapes with cattle and figures. He studied at the West London School of Art – but decided the school was damaging his style of painting.

In 1876 he was living at Sherwood House, 12 Arundel Road, Dorking and in this year married Georgiana Waddingham at St Martin’s Church. They had nine children together who he often included in his work. Two of his of his sons later became painters.

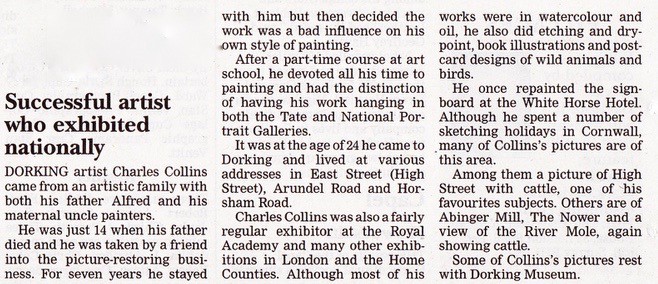

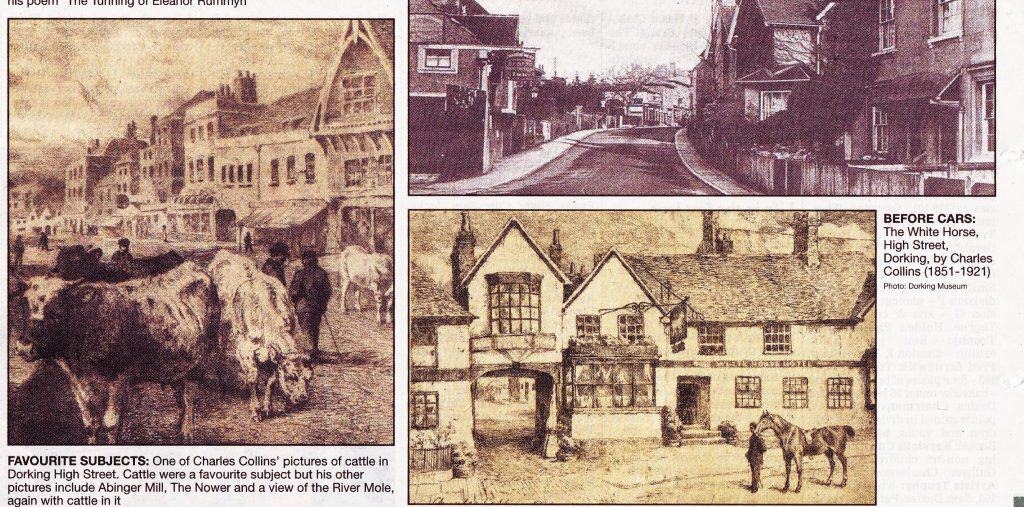

Collins became well known for his figure, rustic and genre paintings in watercolour and oil, but could also work in etching and drypoint. and for many years he illustrated books for the publisher Ernest Nister. He also produced postcards for the same firm. In 1915 he repainted the signboard of the White Horse Hotel.

Although spending time in Cornwall with his friend; Dorking artist; George Gardiner, he remained loyal to Dorking. For many years, retaining the post of Art Master at Dorking High School.

He died in September 1921, after being knocked down in Vincent Lane. Charles and Georgiana are both buried in Dorking Cemetery.

The Museum holds a transcript written by A. E. P. Collins; grandson of Charles Collins.

Alfred Charles Jerome Collins was born on 16 March 1851. His father, Alfred was a highly competent landscape painter in oils who had been taught to paint by his brother-in-law Ambrosini Jerome, the portrait painter, who was a product of the Royal Academy School of Painting. When Alfred Collins died in 1865 he left a family of 8 children, 3 sons and 5 daughters. The young Charles, then only 14 years of age became a bread-winner for his widowed mother and his young brothers and sisters. This he achieved by working at picture restoration for a London specialist in this exacting art. His evenings were spent at night classes in the West London School of Art. He went to Dorking in 1875 on the advice of his brother-in-law, George Kirby, who considered it an excellent area for an artist. He married Georgiana Waddingham in St Martin’s Church on 6 November 1876 and was then living at Sherwood House Arundel Road. His first child, Alfred Francis, was born in 1877, the first of a large family of 9 boys and one girl, the youngest of the family, Brian Patrick, being born in 1895. With so many young mouths to feed it is small wonder that Charles had to supplement his income from landscape and cattle painting in both oils and water-colours with art teaching, becoming a part-time art master at Dorking High School for Boys, then in Dene Street, and also by taking private pupils. These pupils were useful not only financially but by means of sketching trips to the scenic grandeur of the Scottish Highlands and North Wales widened the range of his subject matter. Cornwall, too, with its fine coastal scenery was visited almost annually during the High School holidays. Most of his Cornish trips were to St Mawes, near Falmouth. His usual route to Falmouth was by sea from London Docks on the passenger and cargo vessels of the British and Irish Steam Packet Company which on their London-Dublin service called at various English south-coast ports such as Portsmouth, Plymouth and Falmouth. These sea trips constituted his annual holidays. Once n Cornwall, he was working flat-out, painting the thatched and whitewashed cottages of St. Mawes and the grand coastal scenery.

The sea voyages had another attraction for Charles: engineering in general and steam engines in particular were a life-long interest. He was not only a full-time painter of rural scenes but in his spare time he was a devoted model engineer. I never saw what was probably the first of his models, a railway locomotive which came to a bad end at the hands of his third child, my father, George Edward Collins. He, as a small child, found the engine on a table and pushed it off the table on to the floor. The engine never ran again. Later models comprised a single cylinder vertical steam engine, a steam crane, a steam fire-engine and a second railway locomotive which he did not live to complete. These models showed very considerable ingenuity in the use of the basic hand tools such as files and hacksaws but showed especially his inability to purchase the metals needed for model building. He therefore ‘made do’ with available scrap metals. Thus, where a present-day engineer would rely on an iron casting for machining into a fly-wheel or a purchased gun-metal casting for a steam engine cylinder, Charles would save and melt down the collapsed metal tubes in which artists’ colours were packed. The resulting almost pure tin was melted and cast round short lengths of woven cotton wick made commercially for parraffine [paraffin] lamps. Screws, bolts and nuts were individually made in both steel and brass by means of a screw-plate and home-made taps. His outstanding model was undoubtedly his steam fire-engine. Only the pump has survived and has been presented t Dorking museum by one of his grand-daughters, Miss Joan Edith Collins of Wimbledon. The writer has given to the same institution a contemporary photograph which shows the complete machine on its largely wooden carriage. It is worth putting on record the reason for its construction: in the 1880s and 1890s Charles was a member of the Dorking Volunteer Fire Brigade which was equipped with a horse-drawn manually operated pump. When firms like Merryweather and Shand Mason were marketing horse-drawn steam pumping engines Charles was all in favour of the Dorking brigade acquiring one and urged this course on the Brigade’s commander. He, however, was too scared of machinery to contemplate it. Blocked at this stage, Charles designed and built the steam model to show the faint-hearted brigade commander that he understood the principles of design and the technique of operating a steam fire-engine. The model was in one respect superior to his other models in that he made his own wooden engineering firm of Stone and Turner. The machining of these castings was all his own work. The model, by the way, performed brilliantly. The technical advance of the model fire engine was in part due to his acquiring a bigger and better lathe which had been built by his uncle, William Jerome, of Portsmouth during the Crimean war.

This story can be brought back full circle to the world of fine arts: Charles developed an interest in the black-and-white art of etching: he designed and built his own etcher’s printing press.

The writer is grateful to his cousin, Francis Jerome Collins for additional information on names, dates, etc.

An article on Charles Collins appeared in the Dorking Advertiser on 20th August 2015.

Read about Charles Collins’ son Phillip Collins in Lethbridge, Canada

Last : Walter Waller Caffyn

Next : George Edward Collins