by Peter Brown

May 1993

The view over the snow-capped peaks of the Rocky Mountains made a spectacular climax to the journey from London to Montana. Now the aircraft was descending towards its destination – the town of Bozeman – gateway to the vast American open wilderness that has come to be known as ‘Big Sky Country’.

I was in Montana to make a film about dinosaurs for the BBC children’s series, Blue Peter, to coincide with the release of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster movie – Jurassic Park. Dinosaurs have been something of an obsession since I was a child and that summer of ’93 they were going to be all the rage. This was an adventure film I just had to make, so I managed to arrange a ‘dino-digging’ expedition with palaeontologist, Dr Jack Horner, and his team from the Museum of the Rockies. Jack is one of the world’s leading dinosaur hunters (the inspiration for the hero in Jurassic Park) and in order to get agreement for the trip in time for it to happen, I had promised the BBC bosses that Jack had found a fabulous new dinosaur. Well, sort of. In truth, Jack had assured me confidently on the phone that he would find me a dinosaur, though he hadn’t actually set foot outside the museum as yet. So, when I arrived in Montana to set up the filming, I was very much aware that my job as a film director at the BBC was on the line. You were only as good as your last film, but at least I was there and that was always half the battle.

The Montana Badlands are a notoriously extreme environment. Through most of the year, they comprise deep mud and gullies, either covered under a thick layer of snow or hidden beneath torrents of floodwater from the rains. For a few short weeks in the late spring and summer they become a parched, rattlesnake-infested desert and that is when the dinosaur diggers can get to work. The gullies erode and shift during the wet season and new rocks are exposed every year. They say there are so many dinosaurs in the Badlands that you just trip over them in the desert. At least, that’s what I was banking upon.

The evening I arrived I met up with the dinosaur team to make the final arrangements and early the next morning packed for, what Jack described as, ‘a ten case trip’ into the desert as we loaded on the beers. We drove 150 miles or so in a convoy of 4-wheel drive trucks across the plains until the landscape rose to form cliffs and canyons. There, close to the Wyoming border, we set up a field camp in the scrub.

The landscape looked promising – the distinctive red and orange strata of Morrison Formation that is famed for dinosaurs. Some of the most prized dinosaur fossils in the world had come out of Montana, including specimens of T-Rex. We would be walking on the same land that was roamed by dinosaurs in the Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods.

I spent two days doing some early prospecting with the team. This involved ‘reading’ the landscape, identifying the most likely fossil sites then walking slowly across the rock-strewn surface with our eyes to the ground. Blink and you can miss a vital clue, so attention to every detail – or ‘getting your eye in’ – is the key. I walked with the dino-diggers, moving my eyes across the surface. ‘Ah, is this bone?’ ‘No, fossil wood’. ‘Is this bone?’ ‘No just a weird rock’. Over the hours that followed, the anticipation gradually turned to apprehension and fear. The team found some interesting fossils – fragments of unidentifiable bone and the occasional reptilian tooth – but not the Jurassic Park dinosaur I had promised Blue Peter. A pit formed in my stomach.

All too soon, I had to leave the camp for a couple of days because I had arranged to visit another Montana wonder – the geysirs and hot springs of Yellowstone – to recce another film I was planning to shoot on the far side of the Rocky Mountains. So, with mixed feelings I left camp to drive up and over the four thousand metre (thirteen thousand feet) high snow-covered mountains along the winding Beartooth Highway into Yellowstone. Yellowstone was overwhelming though, in truth, I found it hard to relax at that time.

When I returned to camp, I had just one thing on my mind. Had they found me a dinosaur?

I caught up with the gang playing pool in Buck Eyes Bar at the crossroads in Bridger. The BBC camera crew and presenter were arriving the next day so, as you can imagine, I was dreading the thought of returning to London with a dinosaur film minus the dinosaur. The guys looked at each other with that all-knowing look and handed me a beer. Someone said: ‘Pete, let’s take a hike.’

I just wanted to be put out of my misery, but they wouldn’t give anything away. We drove into the desert, parked up the truck and walked through three miles of scrub and tumbleweed into a canyon. The sun was low in the sky and the shadows were long, revealing the textures of the rock.

‘Look around you, can you see anything?’

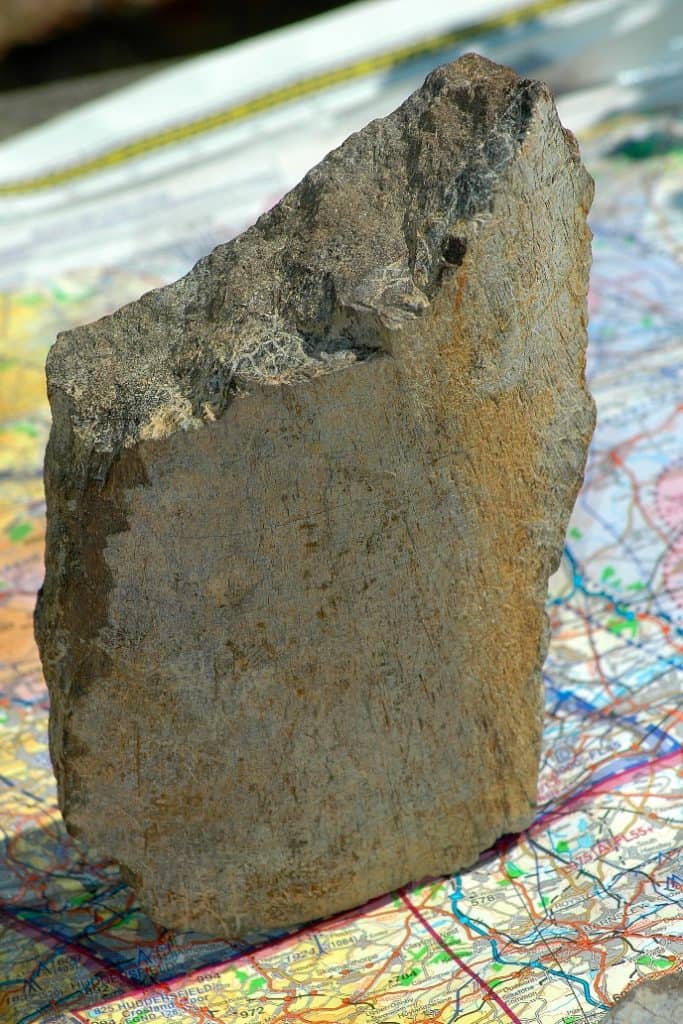

I stood among the reddish-coloured rocks and sand looking for any unusual shape or texture. Something caught my eye. ‘What’s that? And that? And that rock over there?’

I was standing in the middle of a giant dinosaur skeleton, perhaps twelve metres (forty feet) in length, partially eroded out of the bedrock and exposed for the first time in millions of years by the last of the rains. It was a sauropod – one of those cute herbivorous Brontosaurus-type beasts with bad breath that didn’t munch the cast in Jurassic Park. The difference is, this was real and was once a magnificent living, breathing animal.

As the sun set, I just sat there in awe – a fragment of dinosaur femur in one hand and a beer in the other. A wave of emotion swept over me as the fulfilment of a childhood dream combined with the feeling of relief (I wasn’t going to get fired after all!) came together against so beautiful and spectacular a backdrop as the Montana Badlands.