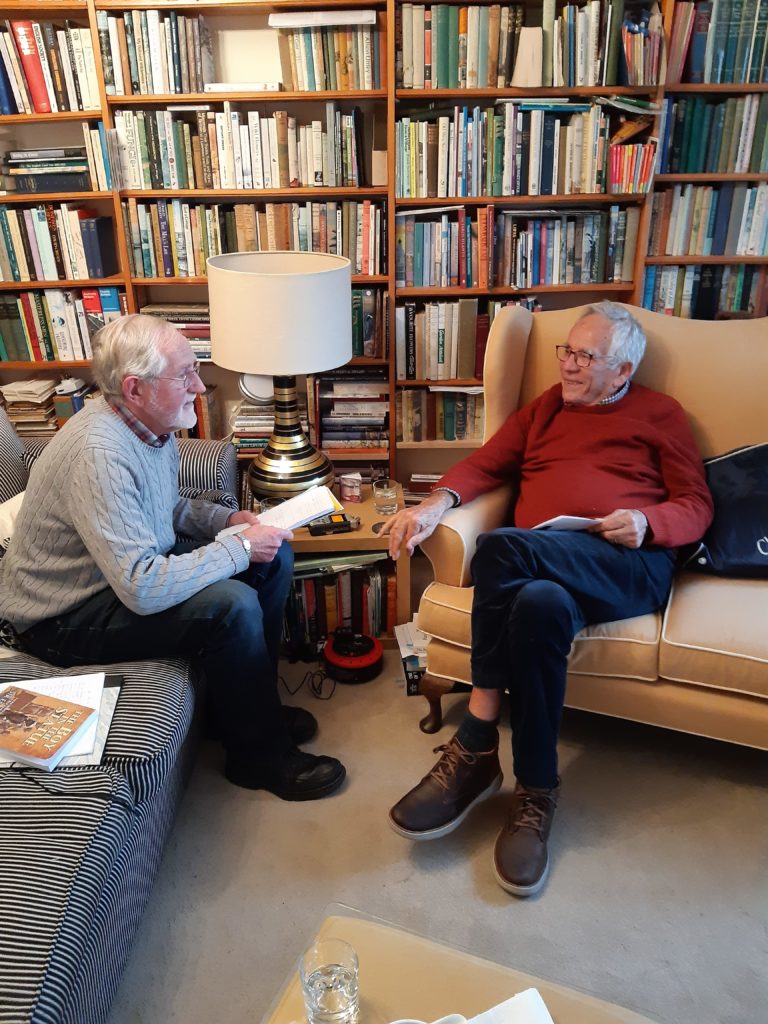

Oral History

- World War Two

- Interview Date : 14th November 2019

- Place : Dorking Surrey

- Interviewee : Sir Erich Reich (ER)

- DOB : 30th April 1935

- Place of Birth : Vienna Austria

- Interviewer : Frank Turner (FT)

[00:20]

Sir Erich, welcome to Dorking, or I should say welcome back to Dorking. Thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. Can I start by asking, so can you explain how it came about that someone born in Vienna in 1935 came as a four year old to Dorking.

[01:28]

And you were in London because you had come from Poland.

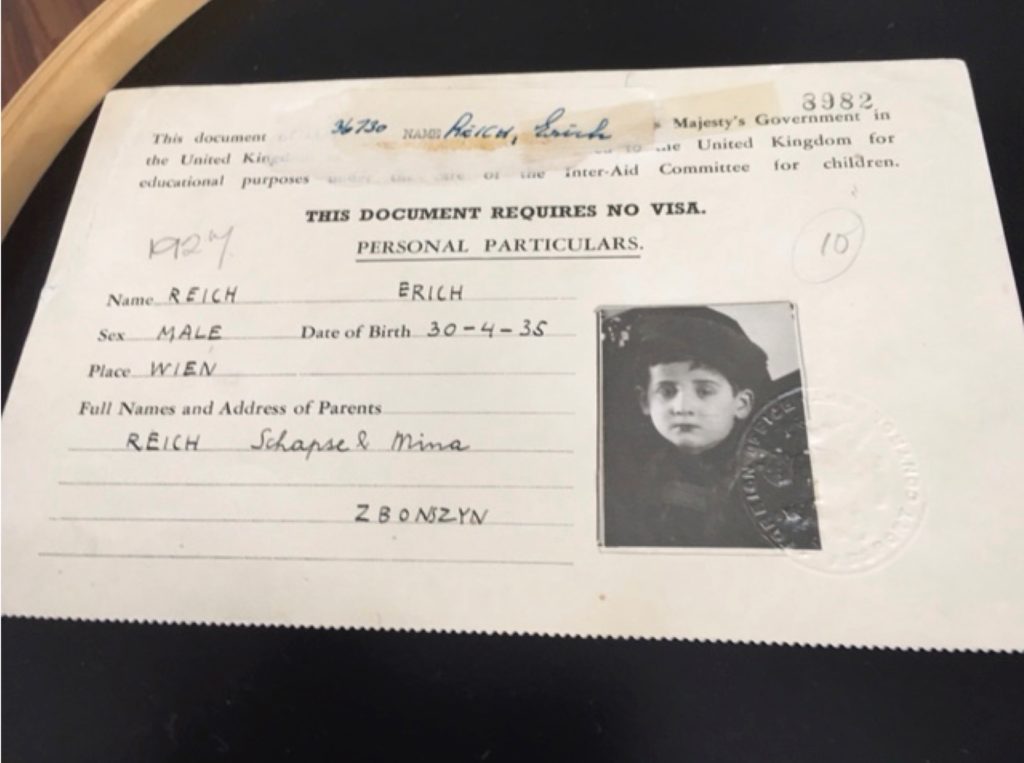

Yes from Poland, we were deported from Vienna because my, what actually happened was that the Polish government had decided that anybody living more than ten years outside Poland had to come back to revalidate their passports. Now in the main they were Jews because there were a lot of pogroms in Poland, particularly in the east of Poland. So the Germans, who by that time had come into Austria already, the Anschluss, they thought it a very good idea and threw out, no one knows exactly how many somewhere between five to ten thousand people to the Polish border for those people who didn’t have Austrian or German passports. Now my mother was already Austrian, her mother my grandmother had sorted that out, but my father wasn’t and he had, they chucked him out, while my my mother had, she was the mother of three boys, eleven ten and four, the four year old is me and we was, well I was only three and a half then and they we went to the Polish border called Zbaszyn, a place called Zbaszyn, and that’s where we landed up.

At the same time Kristallnacht happened which was last week you know last week was the anniversary, and the British Government, there was a debate in parliament and I can’t remember his name at the moment, it always escapes me his name, Noel Baker it was his first speech in parliament and at the end of it, he started at 7:33 I remember that I’ve got the actual thing here from Hansard and he said at the very very end isn’t it time the government allowed the children in that the Jews and the Quakers wanted and I think that changed Chamberlain’s mind because he didn’t want any refugees I must hasten to add. However because of that the parliament and the government decided to allow ten thousand children, up to ten thousand children, between the ages of three and seventeen to come into the United Kingdom.

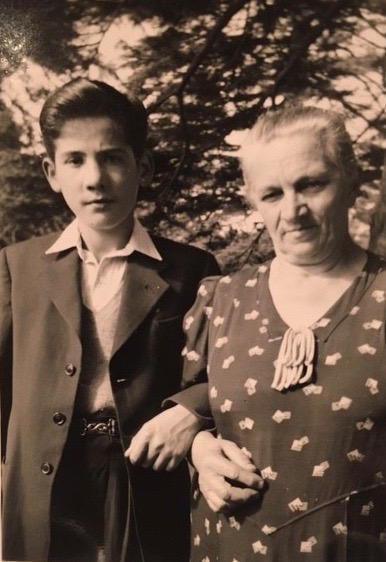

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

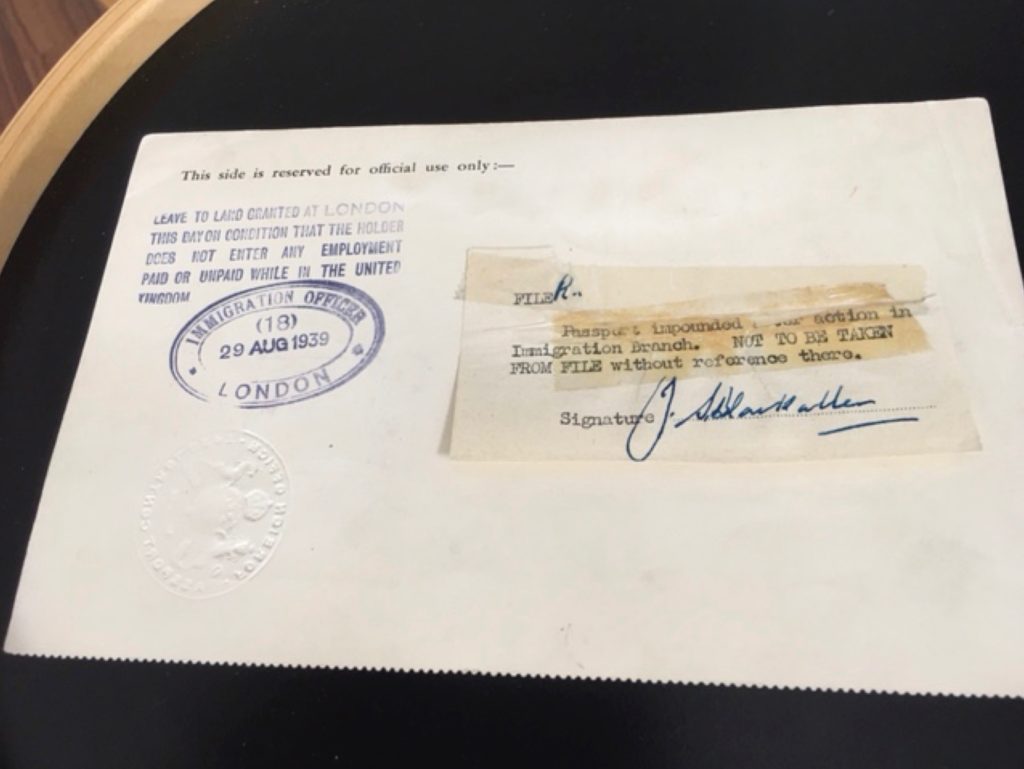

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

I was already in Poland at the time so we came from a place called Gdynia and by ship and the ship was called Warszawa. Now my oldest brother came on the second sailing and my middle brother and I … [sighs] … and my middle brother Ossie we came on the third and last sailing which landed where the HMS Belfast is now, exactly there, it wasn’t there at the time obviously and um what actually happened that he went to Ely to the Jew, because all the children the [incomp] we arrived on 29th of August 39 three or four days before the war broke out, so all the children were evacuated and the school, the Jewish Free School was evacuated to Ely in Cambridgeshire, I was too young, I couldn’t go to school yet so that’s how I landed up in Bloomsbury House and from there Ralph Vaughan Williams brought me to Burchett House in Dorking.

[05:24]

And then I understand you were fostered by Josef and Emily Kreibich

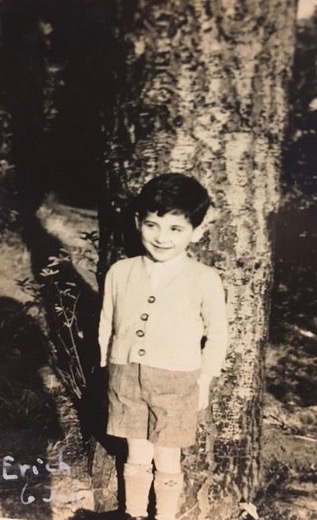

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

Yes, well that’s another story you see, because all the couples there the families were Jewish except that one, they were refugees but they had fled from Hitler because they were socialists and they came here about a year before me, a few months before me I can’t remember when, and they already were grandparents at the time and they fostered me, very interesting, so I went to church St Paul’s, I went to Sunday School there, I did everything.

Well it was, I arrived at the end of August in London and apparently a very well-known composer, Ralph Vaughan Williams, he went to Bloomsbury House, which was the office of the Jewish refugees and said is there anything else I can do, he had brought out Jewish musicians, and they said we’ve got a few children here we don’t know what to do with them, so he said don’t worry, I am the chairman of the refugee committee and there’s a house called Burchett House it’s a refugee home and I’ll take them and I was one of them.

And presumably of course they would have spoken German

They spoke German and I spoke German

So you spoke, so how did you manage you went to school how did you manage with the language?

Well I didn’t manage the first few months, but there was it’s very interesting, when we had the unveiling of one of the statues, somebody wrote me a letter via the BBC and asked could he talk to me and when I talked to him it turns out that he was evacuated from Croydon to Dorking and sat next to me and he felt sorry for me because I couldn’t speak the language I couldn’t I was obviously my skin was all over the place and he said when we went to the playground in St Martin’s school he used to share his Horlicks tablets with me, I don’t remember that at all.

[07:09]

So you just gradually picked up English English yes at school.

Then at the beginning I spoke German then I spoke English but they spoke German to me oh o yes, they never learnt English properly well you see if you come later yes they came at the age of forty five fifty you don’t speak, you can’t change your language no no if you’re a little boy you can it’s easier yes.

And did you encounter any prejudice against you because of the German connection?

It’s very difficult to say because I don’t remember it’s very interesting as I said in the car there are reunions of the primary school and three or four weeks ago we had one at Denbies [Note: Denbies is a vineyard on the edge of Dorking] and two of the people there saw my name, that I would be there and they came, so I said ‘Well why did you come? How did you remember me? I don’t remember you.’ Ah, you couldn’t speak the language, and when the sirens went you fell apart. You see obviously I went through tra… , all kinds of traumatic experiences and I don’t remember them, all I remember is the place itself. I always remember it’s behind the fire station and that’s all I remember.

And and and were you aware of the war going on?

Oh yes, oh yes very much, because whenever the sirens went we went to the shelters and you know in the shelter it was lovely no classes, no nothing , {laughing} and no I do remember the war very well I mean I do remember doodlebugs coming and going and God knows what and on one occasion one of the doodlebugs went over Dorking landed up in south London, and Joseph, Mr Kreibich, he was the first in and the last out of the shelter, he was very good and they always looked after me very very well, you see I think they saved me because I felt part of their family and that’s what it’s all about, I needed that more than anything else, I needed the warmth of a family and they provided it for me, wherever they went I went with them.

Because obviously you were separated from you parents and sadly you never saw them again.

I didn’t even know they existed

[ 09:51]

And do you remember the actual end of the war?

Oh yes, oh yes, very much all the lights suddenly went on. And I remember the bandstand, it was down the bottom there, it’s not there any more and everyone was dancing and we thought it was great fun. And suddenly, I mean I was ten years old and I do remember the end of the war very well, we were all dancing and thought it was a great idea {laughing} but exactly you see at that particular point I didn’t realise what had happened to my parents and meanwhile I had no idea I mean I didn’t even think about it you see the brain, I I’d lost everything.

So this had just become like a new life yes a different life a different life they were my family Dorking was where I lived, obviously their name was Kreibich and mine was Reich but I didn’t even think about it I really didn’t, I played with their grandchildren, Sonia was about two or three years younger than me, so, and they had a little one much later, Ida, she’s still around she lives in Dorking, yes, but she doesn’t want to know anything about it {laughing}

Then post-war you moved to the what was then Dorking County Grammar School now the Ashcombe School.

Yes there was the 11-plus at the time [Note : the 11-plus was a selection exam children took, usually at age 11, after which they went to either a grammar school if they passed and a secondary modern school if they didn’t.] and just before that I had a big accident, I must tell you about that.

One of the days Mr and Mrs Kreibich said ‘Look we’ve got a big parcel we’d like you to take it to our friends the other side of Dorking. But you must promise not to ride in this cart.’ So their oldest granddaughter she begged to come with me. She wanted to sit down while I walked with the cart, but I didn’t, although I promised I wouldn’t I did, I went down the hill, into the wall and the next thing I knew I woke up at the cottage hospital. Now, the cottage hospital was right next to Burchett House, right next to it. So the garden at Burchett House was actually right next to the hospital. I always remember this, she came, I was there for four weeks because my nose was {makes noise to indicate state of nose} anyway she came, my foster mother came and she, first of all she told me off, of course, bit in German, bit in English, told me off for being such a stupid idiot.

And then she with this piece of paper she passed it around, she said ‘You’ve passed your 11-plus, you’re going to Dorking Grammar School.’ Well, I couldn’t laugh because my nose was hurting me {laughing} that’s when I first learnt that I’d passed, you know what I don’t know how I passed, I really don’t, there weren’t many passes two or three of us and I’ve no idea why and how I passed, because I couldn’t speak the language properly, but I did.

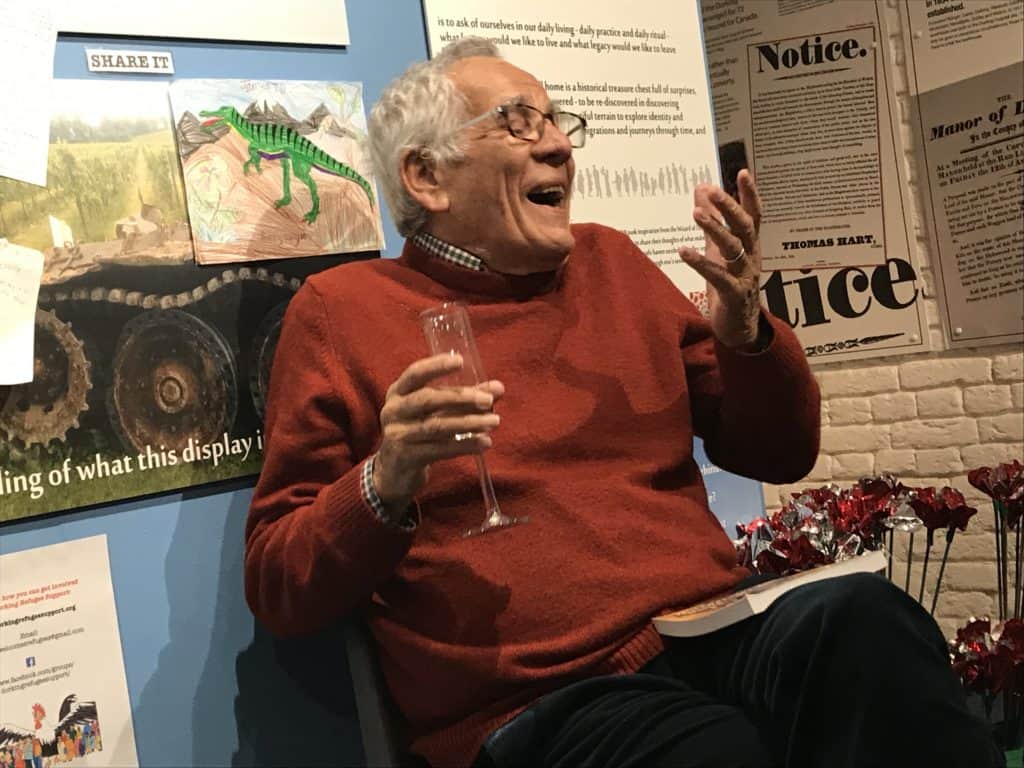

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

You did and you had what, two or three years at the grammar school?

Well at the grammar school in Dorking it was then called, it’s now called Ashcombe but it was called Dorking Grammar Shool and … I was there two years… in the second in the first year they have a cross-country in February don’t ask me why, in February of all places, all times. The first year I lost my plimpsol, that’s what we called them then trainer and I ran in number twenty or twenty one and everyone laughed at me. The second year I tightened them up but I didn’t listen to what the teacher must have told us what to do and suddenly there was nobody in front of me, and I went the wrong way, so they called me back and I still finished first. I’m actually in one of their books, in one of their annual books that I’d won it, I was eleven seconds out of the record, but I wouldn’t have gone the wrong way I would probably have set a new record, but you know that’s life.

[14:33]

Then you left Yes I was in the, they had three… I think three classes every year and I was in the middle, I wasn’t you know I wasn’t a wonderful student, I was just ordinary A,B and C and I was in B.

And then the Jewish community didn’t like me living, my foster mother died, [ Note: ER seems to mean foster father not foster mother] that’s another story. In Burchett House I had a very small room, the door went into their room and in order to go to the loo you had to go… out of their room and somewhere along a corridor, that’s the way it was. The house was given by the way by the Duke of Newcastle and he gave it to the Dorking Refugee Committee for the duration of the war. Anyway, one of those days, it’s very difficult to forget, at the Dorking Grammar School they, I was a reserve in the football, they said would I stay to be a reserve. I stayed, they didn’t need me but I stayed. When I got out, there were no, remember there were no telephones, no mobiles and so when I got home they were furious with me because they didn’t know where I was. I was told to go to bed without any supper, no matter how much I cried and shouted.

I went to bed, and in the middle of the night I heard a commotion, I opened the door and my foster mother came to me and said your dad has died, your vater, that’s what I called him, he had a heart attack, and remember the difference between the Jewish religion and the non-Jewish religion is that the non-Jewish you bury for certain three or four days later, whereas in the Jewish religion you have bury somebody when they die within twenty four hours. He lay on the bed and I had to pass him every day for five days. That was horrible, I mean I remember smelling the they obviously put all kind of things on him. So, the Jewish community didn’t like me living with a foster mother who was non-Jewish so at the end they persuaded me to go to London.

Well you know I was then twelve or thirteen I can’t remember any more, and, but they put me into a very religious school and I lasted there exactly one term. It was I mean it was very nice it was a boarding school, the boarding part was in the Vale of Health near Hampstead Heath, but I couldn’t stand it, it wasn’t me. So I went to my aunt who lived at Haifa at the time in what was already then Israel and my oldest brother was already there he was, he wasn’t exactly fighting, but he was in the army, the airforce or the army I can’t remember which and I went to her, she didn’t have any children, and she couldn’t cope with me, so I found a cousin on what was called a kibbutz , a communal settlement, I found a cousin there who spoke actually spoke a bit of English, because remember I couldn’t speak the language and they all laughed at me because I tried very hard, eventually I learnt it of course, I now speak fluent Hebrew, but at that time I couldn’t and it was hot and there were flies , Oh God, don’t ask, so it wasn’t exactly what I was looking for, God knows what I was looking for, but there was a school there.

[18.45]

And I went to school until the age of eighteen, we worked three, from the age of sixteen you tended to work for three hours a day. Before that in the class, you see there was a huge difference because the school and the classes, you had no homework and nobody ever told you, you have to do this and that. So when there were English classes I was free, so I went down and played basketball, the only problem was the rest of the class came with me. [laughter] But you know, it’s very interesting the way the kibbutz was set up at the time, because I will always remember both my literature teacher who was a professor in Germany or somewhere, my music teacher, you know these are people that you remember because you weren’t forced to remember, and that is a big difference, whereas today even there the same thing the kibbutz is not a community settlement any more, it was but it isn’t any more, and you just learn to be one of them.

There were only about fifteen of us or twenty of us in any particular, what I do remember when I first arrived my cousin says go and have a shower, I’ll show you your room, so I went, I was thirteen coming from Dorking, I went to have a shower and then three girls walk in, undress and have a shower, so I ran for my dear life [laughter] that was my introduction to kibbutz life This never happened in Dorking. No, it wouldn’t happen in Dorking, it doesn’t happen there now either, but at the time you know we were all communists and you know. So anyway, that’s what happened there.

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

When I was eighteen I went into the army. It was an ordinary battalion and then I volunteered to the paratroopers and I was in the ’56 war, very interesting, I was already reserves, we were called back and I said well what am I doing so the guy says to me ’You see that Piper plane you’re going on that and you’re going to find the battalion that jumped at the Mitla Pass’, the Mitla Pass was very famous at the time. So I said to the pilot ‘Do you know where we’re going?’ ‘Oh I know everything’, that’s very Israeli, he went and I looked out and said ‘You know I think we have just passed the Suez canal, you’ve gone a bit too far, back we go.’ And we went back and we … my officer was responsible for me shouted at me through these [inaud] or another and I said we’re coming we’re coming back, and as we’re going to the Piper plane I saw an Egyptian aeroplane coming. So I said the pilot ‘I think we’d better run away.’ And we did and he strafed the aeroplane and it went up in flames and that was the end of that. So I told my battalion officer ‘When you come I’ll be here, I can’t go anywhere else, and then we went down to the Suez canal.

[22:33]

And then after your time in Israel you came back to Britain Yes I came back because your middle brother was ill Yes I came back, after I finished the army my aunt said ‘Now look your brother isn’t very well’ she didn’t tell me what he had ‘Would you like to go back’. Now her husband, my uncle, he leased ships so I went on one of the ships, one of his ships, to Marseille and I dawdled around, I had an uncle in or a cousin or something I don’t know in Lyon so I stopped there for a couple of days and then I went into Paris by train and, of course, typical English, when I get to Victoria station I said I want to get to Walthamstow, so the guy says ‘Yes you go here you go there’ and there was a bus standing there going to Walthamstow.

Any way I arrive.. that’s where my brother lived and I went as I got there there was a note on his door which said I should go next door they told me they were already sitting in in, in the Jewish religion you sit Shiva you sit seven days after the burial of your husband or whoever it is and so I was a bit too, he knew I was coming but I was too late and he died of cancer. Now the reason he died of cancer is quite interesting he was born with diphtheria and osteomyelitis and in Vienna at the time they gave a lot of X-rays and from that he caught cancer and he died at the age of twenty seven and left three boys, three very young obviously, very young boys, so I stayed.

I remember coming to visit my foster mother and on the way I stopped at the school, you know why not. So I stopped at the school, I walk in and there’s the old headmaster Mr Jones and he looked at me and he said ‘Reich, what are you doing here?’ And I said ‘How do you remember my name?’ And he said ‘I gave you the cane three times, you were talking too much.’ Those are my memories of Dorking, you know, I mean, as far as I’m concerned it saved my life, I mean not literally but I’d then become mentally sort of unstable, I was stable and I say so in the book it’s quite important that … I had a sort of a way a control, somebody controlled me, I mean their son, the Kreibich’s son Rudy was his name, he worked in Gomshall [Note : Gomshall is a village a few miles to the west of Dorking] which is very near here, there used to be I don’t know if there still are, there used to be a woodwork, a woodwork factory factory there and he used to work there.

He worked there and Mr Kreibich, that’s my foster father he did all the carpentry in Burchett house and I have a copy of a letter from Vaughan Williams to Emily my foster mother saying how sorry he is to hear that Joseph had died. So he was important.

[26.05]

Now what’s very interesting I, there was a book came out called RVW Oxford University Press about Vaughan Williams, so I wrote to Oxford University Press and I said now look I was in Dorking and he was in Dorking maybe you could get me in touch. The next thing I know she, Ursula is her name, she rang me and she lived not very far away from me, she’s dead now and she said ‘Why don’t you come and have tea and have some sherry?’ [laughter] So I went there, but I don’t think she knew very much about what Ralph Vaughan Williams did before, she’s the second wife. There’s a documentary about him, I don’t know if you have ever seen it. I think in Leith Hill they have a they have every year a music festival a festival for Ralph Vaughan Williams yes, I have a lot of his records, I’m not that keen on his music but it doesn’t really matter.

[27:34]

So you went on to have a long career in the travel industry and you eventually set up your own Classic Tours

Yes yes. Well you see what then happened it’s very interesting I went when I came back here I went to one of these places to look for a job and the guy who was a South African Jew and you know I had to write you know you had to put in who you were, but I was an officer in the Israeli army, so if you were an officer I’ll get you a job, he was Jewish you see, so he got me a job in some small company, computer company, I knew nothing about computers and then I said, this is no good.

I managed to get into Thompson Holidays and they send me off, the Thompson organisation send me off to the travel Thompson Holidays because, if you recall, I think in the early sixties they did these very cheap weekend to Majorca, and what then happened was that the paperwork came in, there were no, computers weren’t around then so there was a lot of paperwork and it piled and piled up, and they asked me to sort it out, which I did, took me six or seven weeks, but it was all sorted out so they made me a director, don’t ask me why , but director they made me so I said thank you very much and I stayed there, this was near Camden Town, and what I do remember I was Israeli.

I didn’t have a British passport at the time and I organised, I said let’s do the weekends in Tel Aviv and in Moscow, you know something interesting, so we organised that and the Russian, the Soviet, it was then the Soviet Union, the Soviet Ambassador came and I showed him around telesales and one of the girls asked him ‘Are there any visas you don’t allow in?’ so he said ‘Yes, South African and Israeli.’ Fine. We make it to my office, and you know, and we talked a bit and then he said this guy says ‘ Mr Reich have you ever been to the Soviet Union?’ I said ‘No, I’ve got one of your passports you don’t allow.’ ‘Oh don’t worry, I’ll sort it out’. Which he did. [laughter] And then, the Tel Aviv one they came from El Al, same thing, but they talked together to each other in Hebrew, which I understood 100%. ‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about’ I wanted seventy seats. ‘I don’t think he’s, he’s doing, there’s something wrong here.’ So I said ‘You know what let’s start’ I said in Hebrew ‘Lets start again.’ And that was the end of that, so they realised that they couldn’t speak to each other in Hebrew. So I worked in the travel, I worked in Thompson, and then I was headhunted for a company called Peltours which is, well it’s now South African but it was Israeli, it was set up in, it stood for the Palestine Egypt something or the other, it was set up in Egypt, and I worked there for a while, and then I went into Thomas Cook, and Thomas Cook of course has just gone under, I get my pension from Thomas Cook [laughter].

It’s there at Thomas Cook I became Director of Tour Operations, and we did Aida in Luxor. I I like history and I knew that Aida takes place in Luxor in Egypt, so this guy, this Egyptian, he was in Vienna, sent us an e-mail and well it wasn’t an e-mail it was something else I don’t know what it was and I said ‘Yes, we’ll take it’. So I organised, I knew someone at The Telegraph, it’s very interesting because there were 600 responses wanted to go, including Michael Heseltine, he came in his private jet or whatever it was, and we had Aida in Luxor, now it’s very nice to see, you know near the Nile, you see the real Egyptians in this, Aida is all about Egypt. Anyway, I get back and I have two letters on my desk, one from my boss, I knew what that was, he didn’t like me, and one from a guy called Tim Renton, he was then the Minister for Foreign Affairs or something, inviting me to Lancaster House to see his counterpart Boutros Ghali Ghali [Note : the name is actually Boutros Boutros-Ghali] so I said ‘Well why do you invite me, what’s all this about?’ He said ‘Well you know because of Aida in Luxor and once you said yes all of Europe said yes, Thomas Cook is a big name and we’d like to invite you.’ So I went for lunch there, they lauded me and God knows what, and then I went to see my boss, who fired me. [laughter]. Now that’s when I set up my own company, because we just didn’t get on. I mean I did Luxor but I made them money, some six hundred thousand quid. So you know.

[33:19]

And then through your Classic Tours you raised something like ninety million pounds for charity.

I I through Classic, I set up Classic Tours and the idea was to do bike rides and treks all over the world

To raise funds, and the first group was from Dan to Beersheba , now why, because, because King David, we’re going Back to the Old Testament now, collected taxes from Dan to Beersheba, that was the extent of his kingdom, which is only about four hundred miles [inaud] kilometres, so I said to I remember I remember this like yesterday, somebody came and my company was having its problems and somebody came from the British Heart Foundation and said ‘Would you give us some money?’ I said ‘No I’ve got a better idea. Why don’t you do a bike ride in the Holy Land?’ And he did. The first bike ride I had was with the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society in Scotland, that was a Christian outfit, and remember my background is Christian and Jewish you see and the Jewish organisation called Ravenswood, I have a friend there and his daughter is handicapped and we had, how many riders did we have, we had a lot of riders, can’t remember offhand how many, two hundred and forty riders that’s it, and they raised six hundred thousand quid which was a lot of money at the time, it’s twenty years ago, twenty five years ago. So the British Heart Foundation then came and we you know bit by bit, now it’s very interesting, the British Heart Foundation riders, we were going down the Dead Sea and suddenly there was a rain break, it was October, November, it often happens in Israel, we couldn’t go all the way to Massala we had to change the route and one of the people asked me ‘Is there any difference between our group, this is the EMS group or British Heart Foundation I can’t remember which and the yes it was the EMS group the Edinburgh Medical Missionary and your Jewish group?’ I said ‘Oh yes, there are lots of differences, but I will sum it up in one, you the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society all take cameras and all take pictures of the holy places, my other lot all take cameras, but they take pictures of each other. That that is the big difference. Well we had a lot of groups, forty thousand people and we raised a lot of funds, I mean I’ve retired, so since somebody took over they’ve raised over over , I’ve raised ninety million, they’ve raised a hundred, another ten million. So it’s quite a lot of money and I remember coming back, I rang home one day and I said ‘Look I’ve got to go to Muswell Hill which is very near Highgate’ and my wife said ‘Look, come in on your way’ I said ‘What for?’ ‘Well, you’ll see.’

Photograph courtesy of Sir Erich Reich

I came in and she was standing still in her morning dressing gown, the big brown envelope which said on it very private and confidential, but it was open [laughter], needless to say she had seen it and in it there was a piece of paper and the Prime Minister was Gordon Brown at the time says would you be amenable to I didn’t know what, I had a good look become a knight, so for two days I thought about it. Well you know I’m an orphan, I was in the Israeli army, you know it didn’t really sit with me very well but in the end I said yes and I’ll tell you why. I got it for two reasons – one because I’m the Chairman of the Kindertransport in the United Kingdom, and I’d raised a lot of funds, and I knew that both of these people would be very happy for me to get, because it’s, it’s, it’s for them as well. So I said yes and I was right because they both felt really proud that they were acknowledged the acknowledgement . So that was in two thousand and ten and yes well.

[38:15]

And do you think your time as a refugee affected your subsequent adult life?

Well you see it’s very to learn or to know, I’m I feel very …. complimentary to the Brits, the British, because they allowed me in, if they wouldn’t have allowed me in I wouldn’t be here, nor would my children be here nor would my grandchildren. So I will always remember on our seventieth anniversary we had a do at the Jewish Free School in London and Prince Charles came. Usually we invite, we invite anybody from there through their office, they always say no, he comes back and says yes. He came and he gave a very short speech, but at the very end, I’ll always remember this he said ‘I’m so glad the government of the time allowed you in, because you’ve given back so much to this country.’ And it’s true, on the one hand I feel that refugees, you don’t know, when they’re very young, that’s why I’m very involved with the Safe Passage Lord Dubbs

Because unaccompanied children you just don’t know, they get a good education a decent education and they’re looked after they may, they will contribute. They aren’t what today’s world they think that all refugees will be killers, but they’re not, not while they’re children and not if they’re brought up in a society that is against murder and against killing and I feel very strongly about that, and as far as I’m concerned, I mean I was saved by the Kreibichs because they gave me a safe haven, they gave me something I could… live and …feel safe about, because prior to that it was just, and somehow I have managed to take it all out.

[40:32]

And do you see any similarities or differences between your experience and the experience of refugees today?

Well, there are differences even then there were differences because you see I was one of the younger ones, so I don’t remember much. Whereas the older ones remember their culture, they remember their parents, and remember that some of them came at the age of up to seventeen, so they would certainly remember, because I remember things when I was eight or nine. So they are, they, they look backwards always and I always look forward, because at the end of the day what’s happened has happened, and I write at the end of the book there’s a poem by Tennyson, which says you know, I’ve got it here somewhere, I can’t, but what it actually says , that even though bad things have happened you never know what the future will be. It may lead to good things, and I think that’s very important.

Because you were just four as you were saying other people felt more the dislocation, uprooted from their culture, their language, but you had less to like unlearn.

And there are quite a few who are against the fact that the British Government only allowed children in.

Having said that, of course, many more came before that, they were older, they weren’t just children, and you’ve got to remember that the English allowed in more people than anybody else. The Americans if you remember I don’t know if you recall there was a boat that went all the way to America with refugees, children, and then came back via Cuba, Southampton, where half came off and back to Hanover or Hamburg or somewhere and they were all killed. So it’s very important to understand that, and that’s why I don’t understand today out of the , I think Dubbs asked for ten thousand children over ten years, do you know how many have come so far, four hundred. And that’s why I feel, I know they are a bit older and it’s not the same and it’s not organised but… there’s something about it that the guy who spoke in Parliament, eighty years ago, he was Labour, he was a very very, I mean, he won the Nobel Prize by the way and he won a bronze medal at the Olympics, he’s the only person in this world has got both [laughter] but, you know, it’s very important to understand that, it’s very important to understand that children, if they’re caught when they’re young and I’ve spoken to some of them, they’re abit older obviously because they have to come all the way from Syria, they have to come from Iraq, Abyssinia, it’s a long way and some of them walk all the way, so it is a long way, anything to get away from it, from the bombs and the, I mean I remember my son, my older son Allon, he’s in films, and he had a friend who went to Crete and in Crete there was a Syrian family, a doctor, his wife and two children, and this friend asked this doctor ‘What are you doing here?’ He said ‘Well I used to live in Aleppo, and one day someone well -dressed came in with a parcel and said ‘You’re going into the centre of town, there’s a bomb in here, and if you don’t go we’ll kill your family.’ So he decided to leave.

It’s not exactly the same because the Nazis, they’d organised the murder. I remember going, I say so in the book, with my nephew and, this is the nephew of my brother who died very young, so he doesn’t remember him, and we sit in Auschwitz, and he said ‘You know it’s very similar, you don’t remember your dad, I don’t remember my dad.’ OK his dad died of cancer, but mine died in one of those gas chambers. It was systematic and that is a big difference, it wasn’t a war, and yes there are people who kill for the sake of killing, but it wasn’t systematic. Nevertheless, the children need to be saved in my view.

[45:25]

And have you got any advice for the people of Dorking as to how they can help refugees settle in and feel welcome?

Well, they should you know, if they are asked by the local council to take in children, they should, because they should give them a safe environment, and by giving them a safe environment they will undoubtedly become good citizens. I mean the ones I met, who were fourteen, fifteen, went to school here and I said ‘Well what do you want to do when you are older?’ And they said ‘ I want to be a doctor, I want to be an engineer, I want to be this, I want to be that.’ You know it’s giving them a livelihood.

Sir Erich, thank you very much indeed.

It was a pleasure.

Last : Dorking and the Holocaust