by Joanna van der Lande

For those of you who know of Dorking, a small market town in Surrey, you might be surprised to hear of a short novel (novella) entitled, ‘The Battle of Dorking’, a work of fiction published in May 1871. On initially hearing about this story, and having known Dorking my entire life, I felt somewhat taken aback that anyone would think Dorking could set the scene for a battle, but its author, George Tomkyns Chesney, wasn’t anyone.

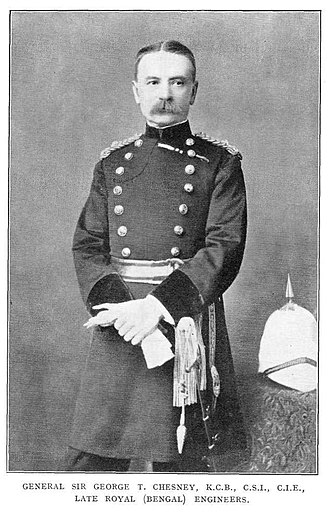

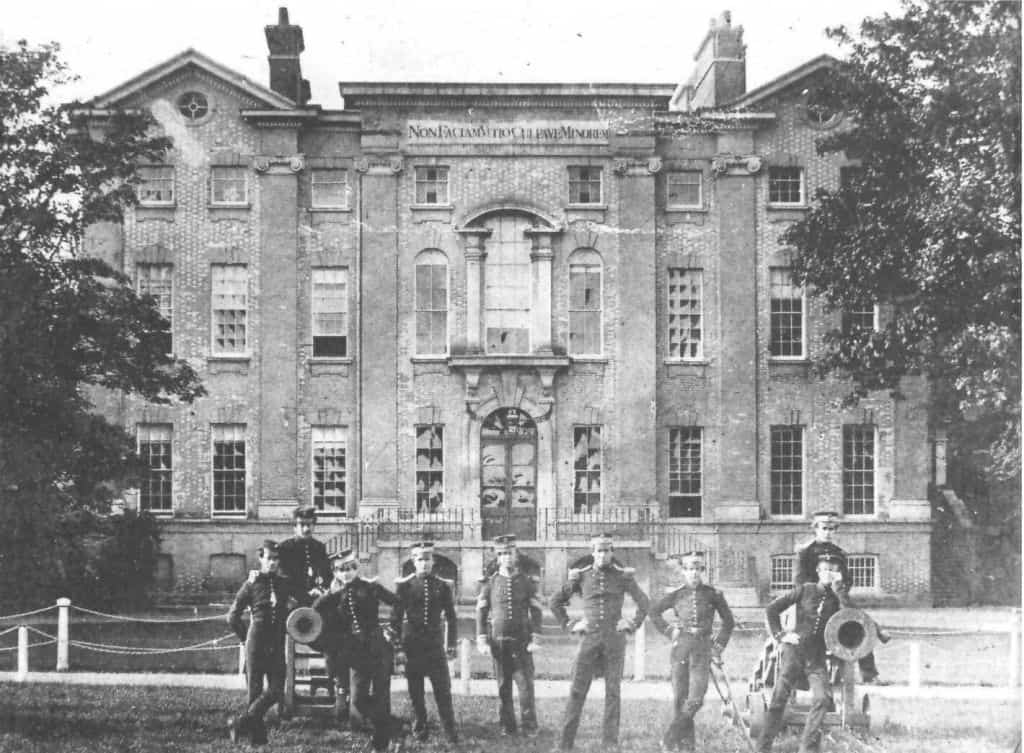

Chesney was born in 1830, training at the East India Company Military Seminary at Addiscome Place in Surrey, an educational establishment for recruitment to the East India Company, with a particular emphasis on training artillery and engineering officers.

A photograph of Addiscombe Place, the principal building of the Seminary, near Croydon.

Its name was changed to the East India Company Military College in 1858

For those interested in Indian and Mutiny history, it has many notable alumnae including Sir Henry Lawrence of Lucknow fame and Sir Robert Napier who was adjutant to General Outram at the first relief of Lucknow.

Chesney joined the Bengal Engineers in 1848 and was brigade-major of engineers throughout the siege of Delhi. After the Mutiny he was appointed head of a new department in connection with the public works accounts and in 1868 published Indian Polity a very well regarded book on the subject. He was the advocator and founder of the Royal Indian Engineering College in Egham, Surrey which was bought in 1870 and opened in 1872 shortly after his novella was first published. At the time of writing “The Battle of Dorking” Chesney was a Lieutenant Colonel.

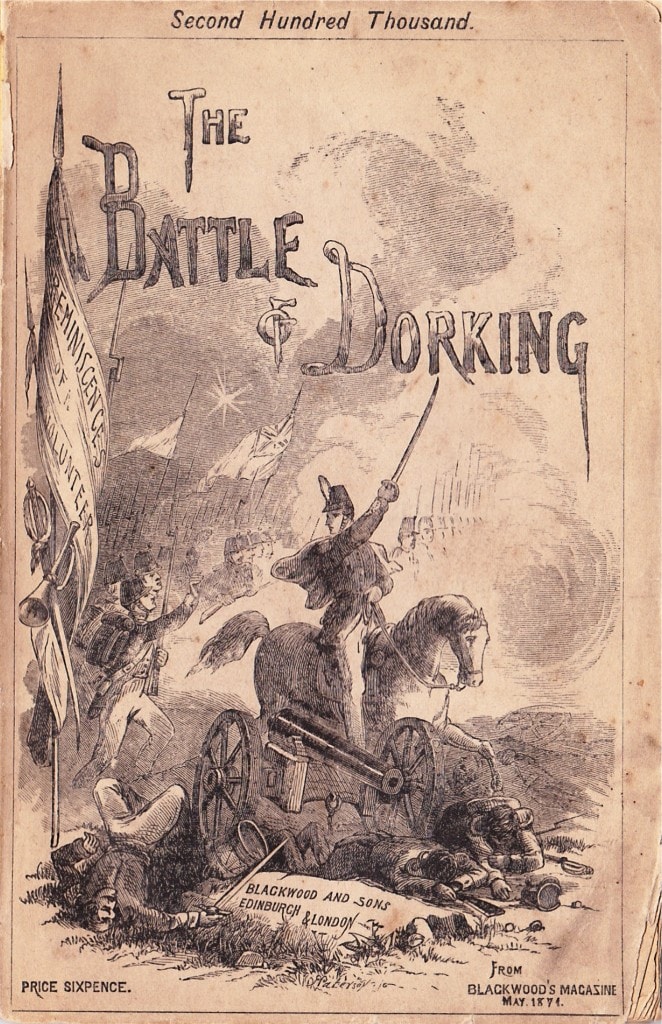

The Battle of Dorking: Reminiscences of a Volunteer was considered the first of a new genre of invasion literature. It was written by a man who was well acquainted with war, as well as sieges and all the associated privations. And with the mind and training of an engineer he knew about planning and preparation. But why write the story at all? The date of the publication provides the clue.

The rapid defeat of the French Army in the Franco-Prussian War which had led to the formation of a single German Empire had caused absolute shock well beyond the French borders. There were reports that the favourite topic of conversation among the German officers at Versailles in January 1871, after the signing of the Armistice, was the invasion of England. Much of the earlier part of the century had been concerned with an invasion by France with their superior army, but overnight the balance of power had shifted and along with it the threat to these shores. Chesney wanted to wake people up to this threat and to the inadequacies of England’s defences; the jittery population found the story all too believable.

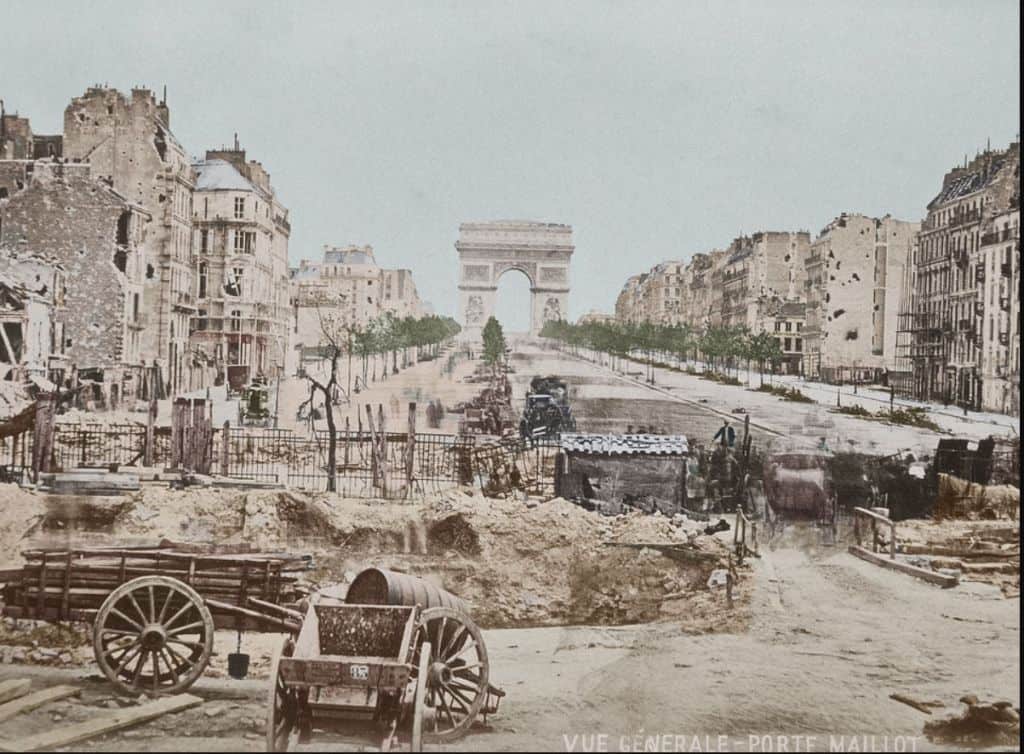

Franco-Prussian war 1870 – 1871 – Paris after the siege

Using the medium of a popular magazine, Chesney wrote to Lord Blackwood, editor of Blackwood’s Magazine, only days after the French defeat. He published the short story in the magazine, initially anonymously and the impact on its well-heeled and conservative-minded audience was profound and immediate. Its fame quickly spread beyond its usual readership to reach a national audience with the seventh edition published by the end of May. It was printed as a stand-alone booklet in June and sold 80,000 copies that month alone with a further 30,000 copies in July. It then attracted an international audience. In contemporary language – the story went viral.

It was a forthright account using Chesney’s experiences as a soldier, cleverly personalising the narrative through the eyes of a Volunteer recounting the tale to his grandchildren fifty years after the invasion. He reflects on the pre-invasion prosperity which England enjoyed and how the country had come to expect this to continue forever. Some of his observations are unsettling even for the contemporary reader; “in our blindness we did not see that we were merely a big workshop, making up the things which came from all parts of the world; and that if other nations stopped sending us raw goods to work up, we could not produce them ourselves.”

The real thrust of his story highlights his concern that the rulers of the Land believed the Fleet and the Channel were sufficient protection. “So army reform was put off to some more convenient season, and the militia and volunteers were left untrained as before…..”

The Volunteer tells us there were an inadequate number of troops and many ships were on other duties in different parts of the world. “It was while we were in this state, with our ships all over the world, and our little bit of an army cut up into detachments, that the Secret Treaty was published, and Holland and Denmark were annexed” though we are not told by whom but he adds that: “…only a few months before, move[d] down half a million of men on a few days’ notice, to conquer the greatest military nation in Europe”. Clearly references to the Franco-Prussian War with the German invasion of France and the annexation of Alsace and Lorraine. The Government hastily declared war without adequate forces in place. To add to the drama and urgency and to build further on the fear of the reader, who believed the navy to be invincible, the Volunteer tells us, “the fleet of the two great Powers had moved out, and it was supposed were assembled in the great northern harbour, and troops were hurrying on board……It was clear that invasion was intended.”

The Volunteer was in London when the papers announced, “New edition – enemy’s fleet in sight!” The story gives us a sense of atmosphere and tension in the bustling city with people going about their usual business in a state of suspended belief. Chesney neatly disposes of the entire navy, “the enemy’s torpedoes are doing great damage” which presumably were “the fatal engines which sent our ships, one after the other, to the bottom.”

The enemy had clearly invested heavily in the torpedo which was in reality very new technology for the time; “The Government, it appears, had received warnings of this invention: but to the nation this stunning blow was utterly unexpected.” The British Government was already showing interest in this new invention but it was only in 1871 the Admiralty invested in the development and production of the torpedo in Britain. One wonders whether Chesney was trying to get things moving along a little more quickly.

Map of the Surrey with the towns mentioned in the Invasion

Rumours of landings then abounded with rather chaotic scenes of volunteer and militia forces sent east when the enemy had landed in the south. The Volunteer was sent to Horsham, which was already occupied by an enemy advance guard, so he was directed to Leith Hill which has an excellent vantage point and from there to Dorking with other forces sent to Reigate and Guildford. The manner in which the Volunteer describes both the landscape and the landmarks suggests Chesney had an intimate knowledge of the area. They bivouacked along the ridge above Dorking, which can be identified as Ranmore and forms part of the North Downs ridge. While walking along this ridge he describes the situation of the town in the valley forming a break in the chalky ridge which then rises up again above the river. This chalky ridge is the steep-sided Box Hill and the river is the river Mole which wends its way north to eventually join the Thames.

The Volunteers notes that,

“The natural strength of our position was manifested at a glance, a high grassy ridge steep to the south, with a stream in front and but little to cover the sides. It seemed made for a battle-field. The weak point was the gap.” The town was emptied of people and the poorly trained volunteers and militia waited with some heated exchanges with the regulars who we are told felt that their presence made the situation more difficult for them.

Photograph © Joanna van der Lande

A view southwards with the Dorking in the far distance, Box Hill on the left and Ranmore on the far right

The well trained enemy reached Dorking with little trouble, and were soon climbing the steep slopes of Box Hill to meet the defenders, while the Volunteer and his troop were waiting their turn on the other side of the valley – their advantageous position of little use against a superior enemy. He then paints detailed and vivid imagery of the chaos, confusion and brutality of hand to hand combat, all on the slopes of Ranmore. Their lines between Dorking and Guildford were breached and the troops fell back towards London with the enemy in hot pursuit. When news reached our now injured Volunteer that Woolwich with its arsenal had fallen, all hope was lost. Railway lines were ripped up but it was all too late.

To add to the emotion he finds his way to a friend’s house for refuge just as it was shelled with a small child, the Volunteer’s god-son, taking the force of the shell and dying. He passes out and on waking hears voices of the enemy in the house. They mocked the retreating volunteers and their lack of training and fitness for battle, with the nameless, but clearly German speakers, portrayed as brutish and boorish. Bearing in mind this was written during the reign of Queen Victoria, whose beloved late husband was German and whose eldest daughter, Victoria was married to a Crown Prince of Prussia, this would have caused quite a stir in itself.

The narrator goes on to tell us that as a result of the occupation, the colonies were taken and Britain’s Empire was lost, while the country was impoverished by the invaders. He lamented that while France still had its rich soil to assist them in their recovery from invasion, “….. our people could not be got to see how artificial our prosperity was – that it all rested on foreign trade and financial credit……They could not be got to see that the wealth heaped up on every side was not created in the country but in India and China and other parts of the world.”

It was a shocking account and even now somewhat unsettling. Chesney was painted in the press both as a hero for highlighting the nation’s deficiencies in defence and alarmist for further unsettling the public and building on pre-existing fears of invasion. Even Prime Minister Gladstone asked for calm in the face of such alarm and he was anxious it would make the country a laughing stock internationally. He spoke openly about it in a speech at the Whitby Working Men’s Club:

“In Blackwood’s Magazine there has lately been a famous article, called “The Battle of Dorking.” I should not mind this “Battle of Dorking,” if we could keep it to ourselves, if we could take care that nobody belonging to any other country should know that such follies could find currency or even favour with portions of the British public, but unfortunately these things go abroad, and they make us ridiculous in the eyes of the whole world. I do not say that the writers of them are not sincere — that is another matter — but I do say that the result of these things is practically the spending of more and more of your money. Be on your guard against alarmism.”

By early June the German Press had picked up on the story in the Allgemeine Zeitung in the form of a fictitious letter from a London correspondent. It ended by saying, “our pride and satisfaction would be increased tenfold if the German Empire were made to extend from the Danube to the Shannon, and embrace India and Australia in its ample folds.” Understandably this caused further anxiety in the British Press and with the political classes. The article then spread all over the world developing a life of its own and was translated into multiple languages.

The story clearly rattled the authorities in more ways than one. In September 1871, significant and unprecedented military manoeuvres took place involving tens of thousands of regulars, reservists and non-combatant auxiliaries. With this show of strength the fear caused to the British public turned more towards satire, with music hall songs referencing the Battle and with any small injury followed by, “weren’t you wounded at the Battle of Dorking?” It all help to defuse the situation.

Nevertheless it never quite went away and between 1889 – 1903 a cross-party consensus in the House of Commons agreed to fortify the North Downs along the route described by Chesney in his fictitious Battle. Forts (previously called Mobilisation Centres) formed part of the London Defence Scheme, running along a 70 mile stretch of the North Downs. A fort was constructed at Denbies on Ranmore, which was abandoned in 1905; while the Box Hill Fort remains largely intact to this day. In 1889 George Cubitt, 1st Baron Ashcombe and owner of Denbies built a Drill Hall at Dorking, which still stands. Changes were also made to ease the pressure on Woolwich with additional munitions and goods depots built with railway-based planning taken into account.

Photograph © Joanna van der Lande

The Battle of Dorking inevitably had a resurgence of interest at the outbreak of hostilities in 1914, with Chesney’s story widely re-published, with prefaces written decrying the nation’s lack of readiness for war and the problems with recruitment. G.H. Powell writing the preface of one such edition published in 1914 says how, “no English Government has ever used its power to impose any artificial restraints upon German trade…” and how the nation had spent its time enjoying life rather than preparing for war “more recent critics have dwelt on the extravagant time and expense devoted to golf. General Chesney would have branded the sensationalist effeminacy of our football-gloating crowds of thousands who might be recruits.” These sentiments are similar to those as narrated by the Volunteer in Chesney’s story over forty years earlier and with some themes familiar to the contemporary reader 150 years later.

During the First World War Dorking became a busy garrison town and many of the local landowners, including George Cubitt, encouraged men to join up while sending their own sons to war, with many never to return. Many of the concerns raised in the Battle of Dorking had to be tackled head-on during that bloody conflict.

While the strategic location of Dorking, with Guildford to the West and Reigate to the East, remained one of importance for years to come, Chesney’s novella appeared particularly prophetic nearly 70 years later when Adolf Hitler issued Führer Directive No. 16 in July 1940, when he set in motion preparations for the invasion of Britain in an operation codenamed “Seelöwe” (Sea Lion) which he prefaced: “As England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary to carry out, a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland as a base from which the war against Germany can be continued, and, if necessary, to occupy the country completely.”

The Germans are said to have joked they knew the route the British expected them to take because of the Battle of Dorking. The defensive network built along much of the south of England remains visible to this day. It’s difficult to walk in the hills between Guildford and Dorking without stumbling across pill boxes – a visible feature of the landscape and often commanding splendid views.

A pill box on the North Downs facing south above Abinger

A pill box just north of Silent Pool, Albury

Photograph © Joanna van der Lande

What became of George Tomkyns Chesney? Was his career ruined as a result of the uproar he caused? Far from it; the debates and actions which followed show his work was not confined to the literary sphere but as a contributor to military policy. Over the years it was often referred to in both Parliamentary Houses. Chesney was a heavily decorated military officer and made a colonel in 1877, major general in 1886, lieutenant general in 1887, colonel-commandant of the Royal Engineers in 1890, and general in 1892. From 1881, he was in the government of India, and was made a Companion of Order of the Star of India (CSI) and a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE). While he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath (C.B.) at Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee in 1887and a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (K.C.B.) in the New Year’s Honours list in 1 January 1890. He was known as an educational and military reformer of considerable standing both in India and Great Britain, where he latterly became a Conservative Member of Parliament for Oxford a few years before he died in 1895.

As for Dorking, it remains a small market town which hasn’t been invaded since the time of William of Normandy in 1066.

© Joanna van der Lande, February 2021

An article originally commissioned by Classic Battlefield Tours https://classicbattlefieldtours.com/