Traditionally Britain relied on the Royal Navy for defence. Its small volunteer army was generally employed to keep order in the colonies. A war on land would require a bigger army. But, unlike France and Germany, Britain had no national service requirement, so there was no pool of trained men available to call up.

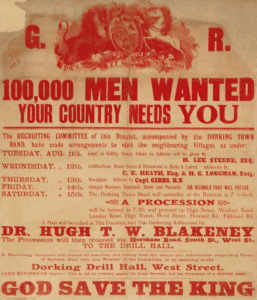

In August 1914 Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, called for 100,000 volunteers to form a new army. The Dorking recruiting committee immediately arranged a series of recruitment meetings. Men joined up from all backgrounds, driven by patriotism, disgust at tales of atrocities in Belgium, or attracted by the prospect of a regular wage.

Henry Cubitt called on farmers to impress upon labourers the need to join up. Leopold Salomons offered every unmarried man in his employment half pay whilst he was serving. Some employers threw men of military age out of work, others refused to take them on, in the hope of persuading them to enlist. And Cubitt warned that when the war was over ‘the principal people’ of the district – who owned farms and businesses as well as employing scores in their houses and gardens – would give preference in employment to those who had served.

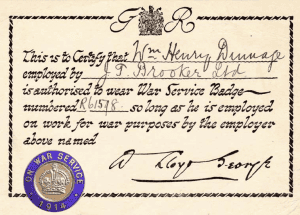

Men who remained came under such pressure to explain why they had not joined up that in October the High Sheriff of Surrey issued badges to those who had tried to enlist but had been rejected.

By September the Dorking & Leatherhead Advertiser estimated that the town had supplied 225 men to Kitchener’s Army and 53 to the territorials. In October the town band played another contingent of reservists off at the station. By December 80 former pupils from Dorking British School, 40 from Dorking High School, and 56% of the town’s postmen were serving.

Dorking district’s first death in action was Arthur Curry on 26th August, three weeks after the declaration of war. The first casualty lists appeared in the Advertiser on 24th October, and the first obituary – of Albert Ready, a porter at Dorking station – on November 21st. By December the paper was running pictures of the dead alongside adverts for Christmas turkeys.

As early as late 1914 the village of Mickleham was struggling to keep its fire brigade operational with the exodus of village men to the services. Boy scouts were filling the gap.

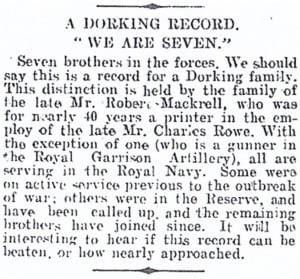

By 7th October 1914, seven Dorking brothers were serving in the forces: Robert, William, Albert, Charles, Ernest, Percy and Frank Mackrell were sons of Robert Mackrell, a retired printer who had worked for forty years at Rowe’s in Dorking. Percy and Frank did not return.

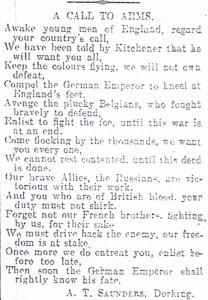

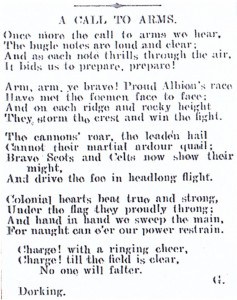

Two calls to arms in poetic form published in the Dorking Advertiser in the autumn of 1914. Poetry was a regular feature in the paper and elevated tone of these recruiting poems is typical.

Posters five feet high in red lettering advertised the recruitment party’s progress through the town and villages with the town band playing them on their way. The week’s activities culminated on the evening of Saturday 15th August with a procession of recruits, accompanied by the town band, from the Rotunda on South Street through the streets of Dorking.

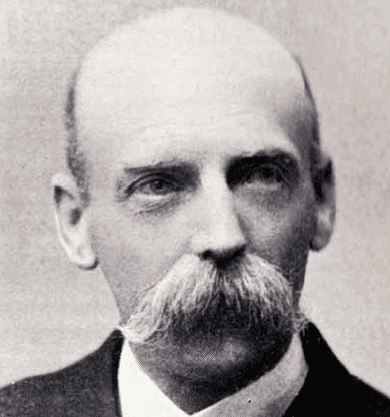

At the fountain outside the Falkland Arms, and at the Red Lion on the High Street, Dr Hugh TW Blakeney told the crowds that England and the Empire were in a perilous position as the band played the national anthems of Belgium, France, Russia and Great Britain. The event brought Dorking’s enlistment figures to mid-August to 80 for the regular army and 31 for the territorials.

The Red Lion Hotel on the High Street from the steps of which recruiters addressed the crowds. The hotel is shown during the general election campaign of 1910.

The Falkland Arms where recruitment parties addressed residents to the south of Dorking. The fountain pictured in the foreground was removed during the blackout in the Second World War as a hazard to traffic after several accidents.

Certificate of War Service issued to William Henry Dinnage. The badge that would have been issued with the certificate indicated that the wearer was on war service, so explaining why he had not enlisted. Dinnage was the son of a boot repairer from Heath Hill, Dene Street. He worked for Taylor and Brooker’s timber yard near Dorking Station, which was carrying out work of importance to the war effort. A considerable artist, Dinnage was responsible for many of the views of the town that are now in Dorking Museum’s collection.

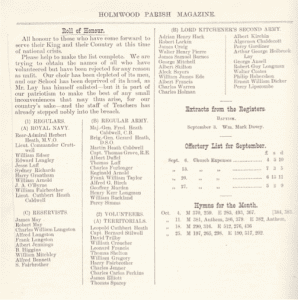

The ‘Roll of Honour’ from the December 1914 parish magazine from St Mary Magdalene’s, South Holmwood. As recruiting continued parish magazines, school reports and local papers published the names of those serving, as much to shame those who had not volunteered as to honour those who had.

Last : The Week Before The War

Next : Urban District Council