The wealth of the mansions was in great contrast to the impoverished countryside. Agricultural labourers were paid only when work was available. They were seldom far from poverty.

Life was hard in the early 19th century. The innovations of the agricultural revolution were ineffective on clay soils. Local farmers could not compete with market prices once cheap corn could be brought in from elsewhere. Fields were withdrawn from production and labourers put out of work. By the 1820s many families were relying on the poor rates for survival.

Stoneheal Cottage in South Holmwood was one of two cottages with gardens, orchards and rights of common kept by Dorking Overseer of the Poor Nathanial Wix in the 1790s. There he provided work to paupers in return for their keep.

Though there was a workhouse in South Street, the parish often made maintenance payments to poor families. But the mass poverty of the 1820s was a huge burden on rate payers. Dorking parish officers tried to persuade farmers to take on labourers at subsistence rates, but this forced wages lower as struggling farmers let go higher paid labourers. And as poor rates increased, cashless smallholders were forced into bankruptcy, creating further dependence on the rates. The almshouses on Cotmandene provided relief to a small number of elderly people.

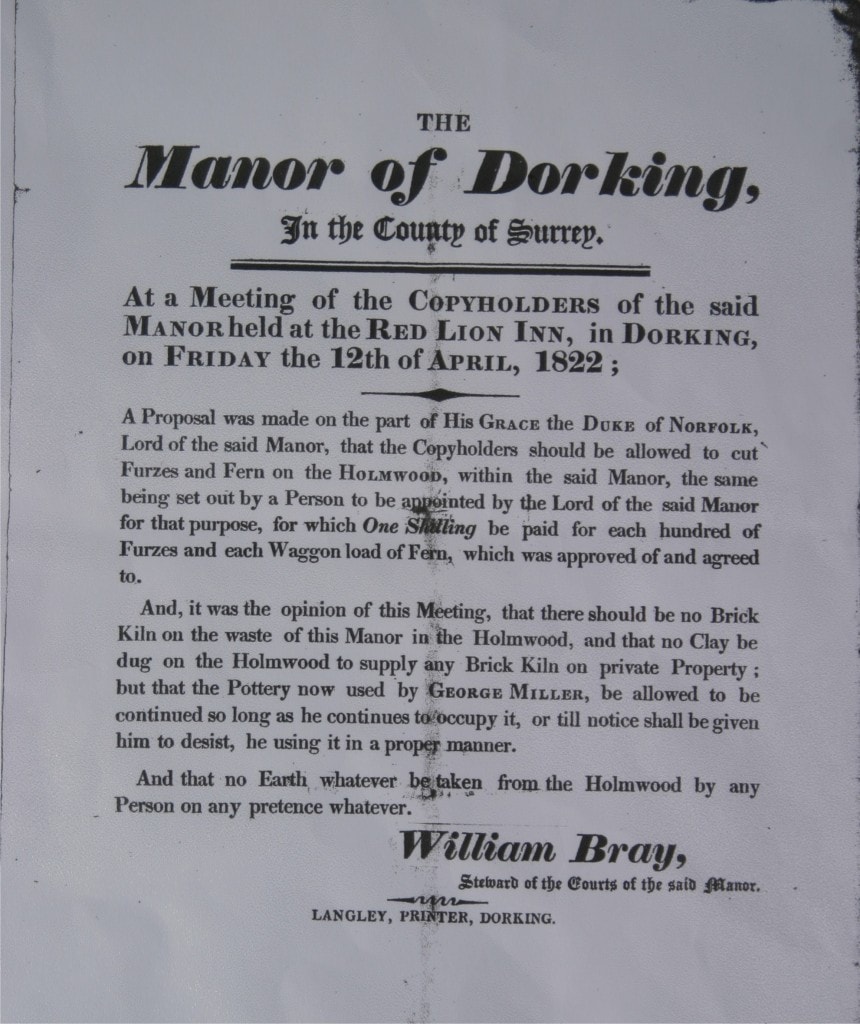

In 1834 the Dorking Poor Law Union was established, covering Abinger, Capel, Dorking, Westcott, Coldharbour, Effingham, Mickleham, Newdigate, Ockley and Wotton. In 1841 the new Union workhouse was built on the Dorking Hospital site. ‘Outside’ relief would only be given in exceptional circumstances; those in poverty would now have to enter the workhouse. Holmwood Common came under pressure in this period from desperate people pillaging its resources – illegally burning lime, stealing gravel, ferns and bracken – and from smugglers and highway robbers. It was, claimed millionaire Thomas Hope, ‘a harbour for thieves, vagabonds and idle and disorderly people’. He supported enclosing it, claiming that selling it off would remove the opportunity for idling and create more legitimate work, so relieving costs to ratepayers. But the argument prevailed that this would throw households with legitimate rights of common into destitution, unable to survive without rights to take wood and graze their animals, resulting in even higher poor rates.

The Museum was contacted by Keziah Rodell, who had written a piece on the Old Poor Law for her A Level. We have published an excerpt from her essay here.

Last : ‘Bread or Blood’

Next : Art and Inspiration