When war broke out Mrs Pankhurst called a halt to suffragette campaigning and set to recruiting – in the hope of winning respect for women’s contribution to the war effort. The national emergency took precedence over the fight for the vote. But other suffrage campaigners, amongst them Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence of Holmwood, were appalled.

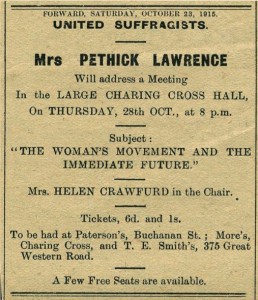

In late 1914 Emmeline left on a speaking tour of the United States. In New York she was asked whether the women’s vote might have prevented war. She replied that it might prevent another war, and announced that the struggle must go on. By 1915 Emmeline was a key member of the United Suffragists and had given her campaigning publication, Votes for Women, to the group. The United Suffragists continued to fight for the vote throughout the war.

The outbreak of war made women like her even more certain that women must have a say in the nation’s most fundamental decisions. Her speeches in New York gave indirect rise to the American women’s peace movement which allied the campaign for the vote in the US to efforts to keep America neutral.

Previously treasurer of Mrs Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), Emmeline took in Belgian refugees on the outbreak of war. Her house in Holmwood became a retreat for her war- haunted London circle: her brother, Harold, returned from Canada to enlist, leaving his wife Evie in Holmwood. Her sister, Dr Marie Pethick, took refuge there from the stresses of night calls to air raid casualties; Emmeline was devastated when Marie collapsed and died suddenly whilst taking casualties to the Euston Road Women’s Hospital. In 1918 Emmeline stood as the Labour candidate for Rusholme in Manchester, advocating a just settlement with Germany as a necessity for the achievement of permanent peace. She was not elected.

Emmeline’s husband, Frederick, was a founder member of the Union of Democratic Control, the leading anti-war movement. Selected as a parliamentary candidate for the Labour Party at the end of the war Fred withdrew his candidacy: in the euphoria of victory an advocate of a negotiated settlement stood no chance of election.

Emmeline represented Great Britain at the International Women’s Peace Conference in the Hague in April 1915, one of only three British women to attend. On her return she campaigned for a mediated settlement and against conscription, and became treasurer of the Women’s International League of Great Britain.

Mrs Pethick-Lawrence (left) on her way from the United States to the International Women’s Peace Conference in the Hague in April 1915. The British government suspended crossings to the Dutch ports to prevent British delegates attending. But Emmeline travelled directly from the United States with the US delegation.

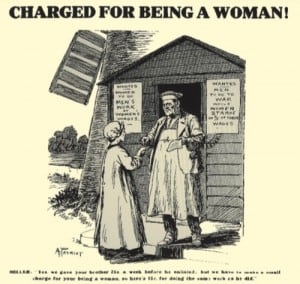

Cover from Votes for Women magazine highlighting government hypocrisy in their contradictory pronouncements to women before and during the war. Started by Emmeline and Fred and once the mouthpiece of the militant suffragettes, the highly political magazine was edited by Emmeline’s friend Evelyn Sharp (who became a Quaker) during the war – and carried prominent articles by Emmeline.

Other women saw the war as a chance to prove themselves; war work, nursing, and the establishment of hospitals proved women’s capabilities. But it was the constant pressure of women like Emmeline which kept the issue of the vote on the agenda. Her Votes for Women magazine satirised the government’s hypocritical attitude to women’s position and the terms of their contribution to the war effort. Had she and others like her not kept the issue in the minds of politicians, it is unlikely that women would have achieved even the limited franchise that they did in 1918.

Operation in progress at the Endell Street Military Hospital run by ex-suffragette doctors Flora Murray and Louisa Garrett Anderson, both close colleagues of Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence. The women originally set up their women-only hospital in France as they had criminal records for suffragette activities. Their acknowledged purpose (in addition to the provision of medical services to the war wounded) was to prove women’s capabilities; the all-female staff took as their motto the WSPU slogan ‘Deeds not Words’. Local woman Daisy Wadling, a driver in the Army Service Corps, died there in 1918 and was given a full military funeral with gun salute in Dorking.